When it comes to PFAS, scientists have found these “forever chemicals” in soil, water and air in sites around the country and the world. Now, researchers have found PFAS in every Lake Michigan fish they sampled and a particularly toxic form of PFAS in most of the lake’s sportfish.

PFAS is short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, which encompass thousands of compounds that don’t break down in the environment. They are used in many everyday items like nonstick cookware, water- or stain-resistant clothing or carpeting, cosmetics, and even toilet paper.

Along with their persistence and growing presence in the environment, these chemicals may have human health impacts, such as impairing one’s immune system, increasing the risk of some cancers, and delaying development in children.

With funding from Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG), scientists from the University of Notre Dame—led by biologist Gary Lamberti and nuclear physicist Graham Peaslee—set out to assess the presence of PFAS in Lake Michigan fish and how these chemicals move through the lake’s food web, which had not been previously studied.

“We tested over 100 sportfish—chinook salmon, coho salmon, rainbow trout and native lake trout—and another 100 or so prey fish from all four quadrants of Lake Michigan,” said Daniele De Almeida Miranda, a postdoctoral associate working on the project.

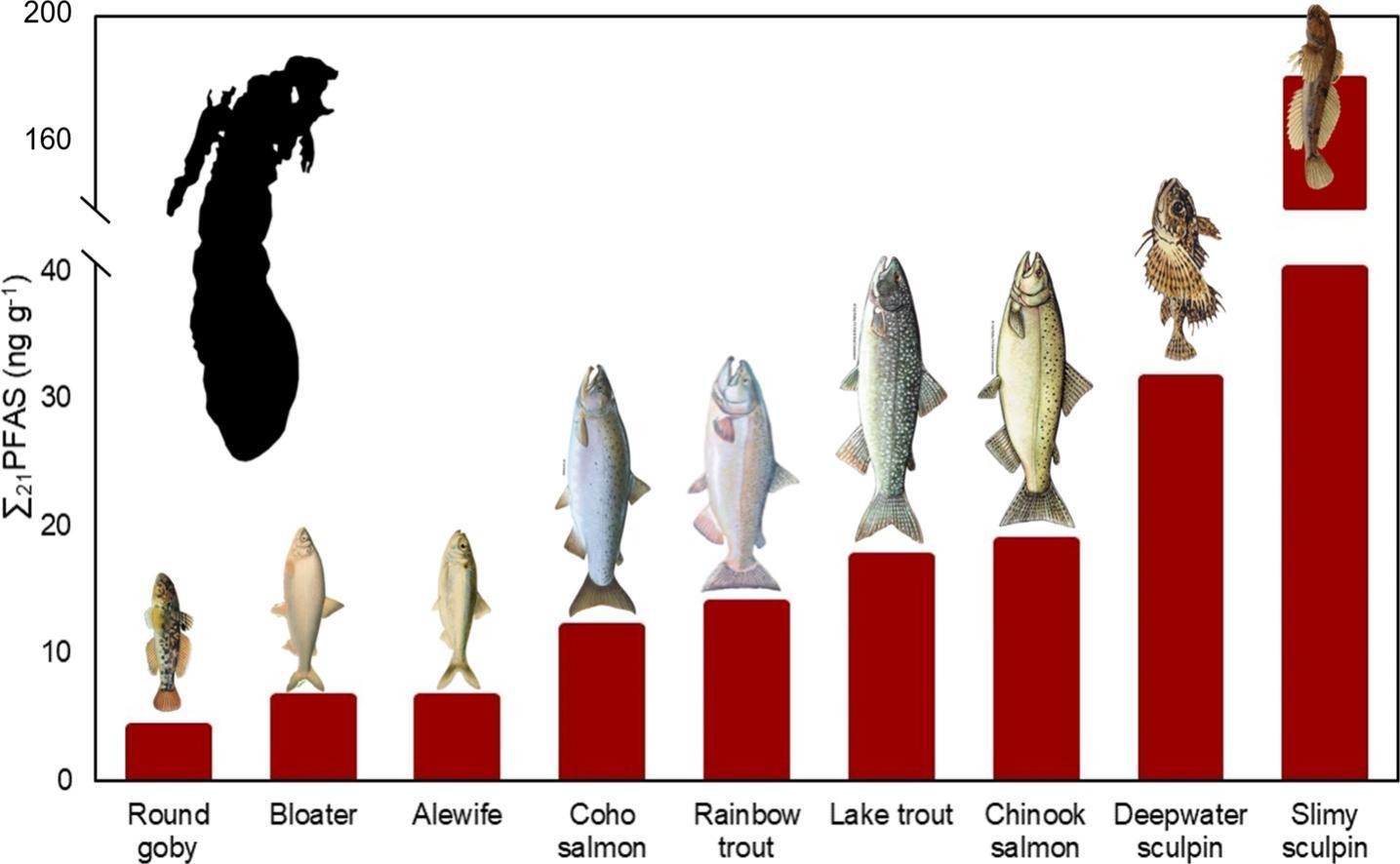

They found PFAS in all sampled fish, both predator and prey, and in similar amounts and composition throughout the lake. The good news in terms of Lake Michigan—the study showed PFAS levels were lower there than in most Great Lakes.

Of notable concern though, was the widespread presence and level of PFOS (or perfluorooctane sulfonic acid) in the lake’s fish. These compounds were identified in more than 95% of sampled fish, especially salmon and trout.

“PFOS are a type of PFAS that are very toxic, even in low concentrations,” said Miranda. “For that reason, these compounds were phased out of production in 2002. Over 20 years later, PFOS are still the main PFAS compounds that we are seeing in Lake Michigan fish.”

These dangerous substances were also more likely than other tested PFAS compounds to bioaccumulate, meaning to move up the food chain from smaller to larger fish, potentially resulting in higher concentrations in popular sportfish.

“While bioaccumulation is straightforward with some contaminants, such as PCBs or heavy metals, it’s not with PFAS,” said Miranda. “For some PFAS compounds we found higher levels in predator fish such as chinook and lake trout, than in prey fish, but sometimes it was more variable.”

Lamberti noted that PFAS uptake by fish can be complicated, and many factors might play a role, such as the smaller fish’s diet or whether they spend time near the lake’s sediments, where PFAS might accumulate. “For example, small bottom-dwelling fish called sculpin had the highest PFAS concentrations of all the fish tested,” he said.

Also part of this IISG project, Peaslee developed a quick and affordable screening tool using technology that involves particle induced gamma-ray emission (PIGE) for analyzing PFAS and the researchers adapted the process for sampling fish tissues. This new approach provides a measure of total fluorine levels, which are a useful indicator of the presence and the amount of PFAS in fish.

The PIGE method was tested using a subset of this project’s sample fish and next steps include expanding that number.

The research team expects this first look at PFAS and their movement through the Lake Michigan food web to help decision makers evaluate the extent of these pollutants in the ecosystem and in sport fish, which may ultimately be on someone’s dinner plate.

This study is published in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a partnership between NOAA, University of Illinois Extension, and Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources, bringing science together with communities for solutions that work. Sea Grant is a network of 34 science, education and outreach programs located in every coastal and Great Lakes state, Lake Champlain, Puerto Rico and Guam.

Writer: Irene Miles

Contact: Carolyn Foley