This summer, 15 Great Lakes educators swapped lesson plans for life jackets as they boarded the Lake Guardian, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s research vessel, and set sail on Lake Michigan. Through the Shipboard Science Immersion program, 5–12 grade formal and non-formal educators worked side by side with Great Lakes scientists for a week—an experience they say will ripple back to their classrooms for years to come.

The Shipboard Science Immersion, which takes place every summer on one of the Great Lakes, is organized by the Center for Great Lakes Literacy. Kristin TePas, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant’s Great Lakes literacy and workforce development specialist and one of the Immersion’s organizers, said the goal is to build Great Lakes literacy among teachers.

“This experience helps teachers become more knowledgeable, more confident in talking about the Great Lakes, and better able to bring that science into their classrooms,” she said. “Often teachers go into teaching science without a research background—so for many, this is transformational. They tell us they feel like real scientists.”

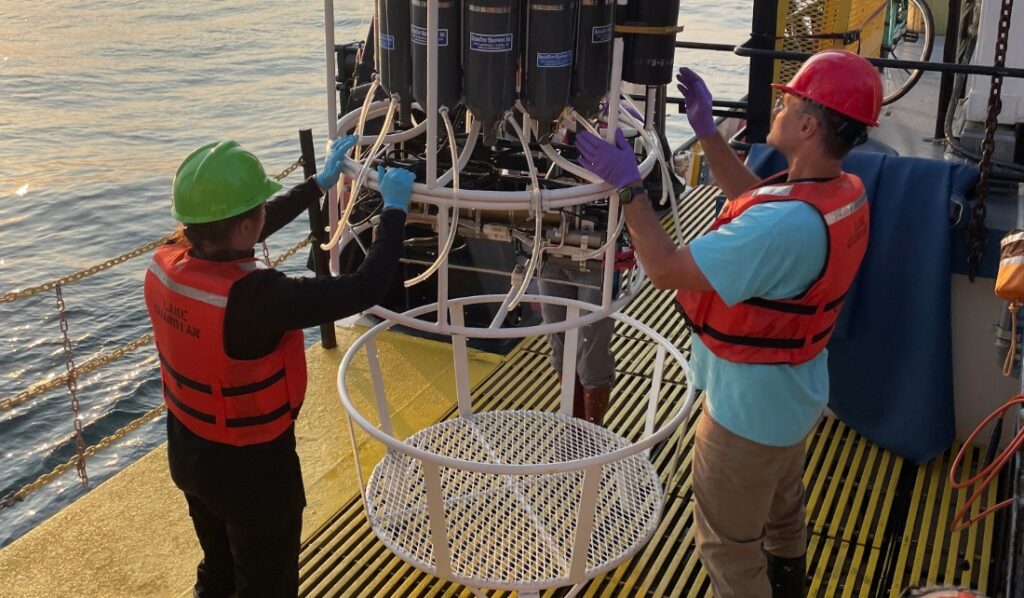

Shipboard Science Immersion educators help steady important monitoring equipment aboard the Lake Guardian. (Photo by Virginia Friedman)

This year, four participants were from Illinois and Indiana.

For Ryan Johnson, a 7th and 8th grade science teacher at Jovita Idár Elementary School in Chicago, the program was a chance to deepen his understanding of the Great Lakes while immersing himself in real-world science.

“Living and teaching in Chicago along the ‘third coast’ of Lake Michigan, I was drawn to the Shipboard Science Immersion so that I could engage directly with an important ecosystem that I didn’t understand all that well, even after living here most of my life,” he said.

Gerard Kovach, who teaches science at Decatur Classical School in Chicago, said water quality has always been close to his heart. Growing up on the Vermilion River in Central Illinois, he developed an early passion for ecology that he now brings into his classroom. Kovach, who was recently named Educator of the Year by Friends of the Chicago River, uses hands-on teaching by building aquaria that replicate local ecosystems and providing fishing lessons to students.

“Water ecology is something I’ve brought into my teaching for years,” Kovach said. “The Shipboard Science Immersion program felt like the next step.”

Both teachers described the demanding but rewarding rhythm of life aboard a research vessel. Johnson recalled deploying nets at odd hours, shifting schedules around weather delays and logging sonar data late into the night. “Every task aboard the vessel reinforced the complexity and importance of running a Great Lakes science expedition,” he said.

Kovach was struck by the dedication of the scientists. “The team was working around the clock, driven by a passion for learning.”

The camaraderie also stood out. With educators, scientists, and crew working side by side, Johnson described the ship as “a living model of the kind of science community I strive to build in my classroom.”

TePas added that the structure of the week itself is what makes it so impactful.

“What makes the Shipboard Science Immersion so powerful is that it’s a full week on the ship, with no distractions. Teachers are fully immersed, by collecting samples, working in the lab, analyzing data, and presenting their findings. That kind of experiential learning doesn’t just build knowledge; it reignites passion for science.”

Educators listen intently for instructions from Great Lakes scientists. (Photo by Rob Fish)

Both educators are already bringing shipboard science back to their students. Johnson plans to have his students model food webs, analyze water quality data, and simulate sampling techniques. He is also exploring a Trout-in-the-Classroom program to connect students directly with local ecosystems.

Kovach hopes to expand his school’s aquaponics work into “window farming,” incorporate round goby dissections into ecology units and invite scientists from the ship into his classroom. He and Johnson also plan to connect their students virtually to collaborate on Great Lakes–based projects.

Beyond classroom activities, both educators said the program will have lasting effects on their teaching careers. Meeting scientists, college students and fellow educators underscored how their efforts benefit local communities who rely on the Great Lakes for drinking water, recreation and economic value.

“It rejuvenated me,” Kovach said. “It’s those summer experiences that give you a bunch of new activities and perspectives to explore with students.”

For Johnson, the biggest takeaway was perspective. “This trip helped me fully understand the importance of remaining flexible about some things and rigid about others. Science requires both adaptability in the field and rigor in record-keeping. That’s a lesson I’ll carry into every class I teach.”

The 2025 Shipboard Science Immersion’s crew and educators pose aboard the Lake Guardian. (Photo by Gerard Kovach)