Most people who grew up around the Great Lakes Basin have, at some point, wrapped their fingers around the smooth metal of a fishing pole. Enjoying one of the biggest recreational activities in the Midwest, anglers have often relied heavily on word of mouth, repeated success and even superstitions to find the best places to cast a line. Now, they can also use Fish Atlas, a tool developed by Purdue University and Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, to help them find hot spots for salmon and trout in Lake Michigan.

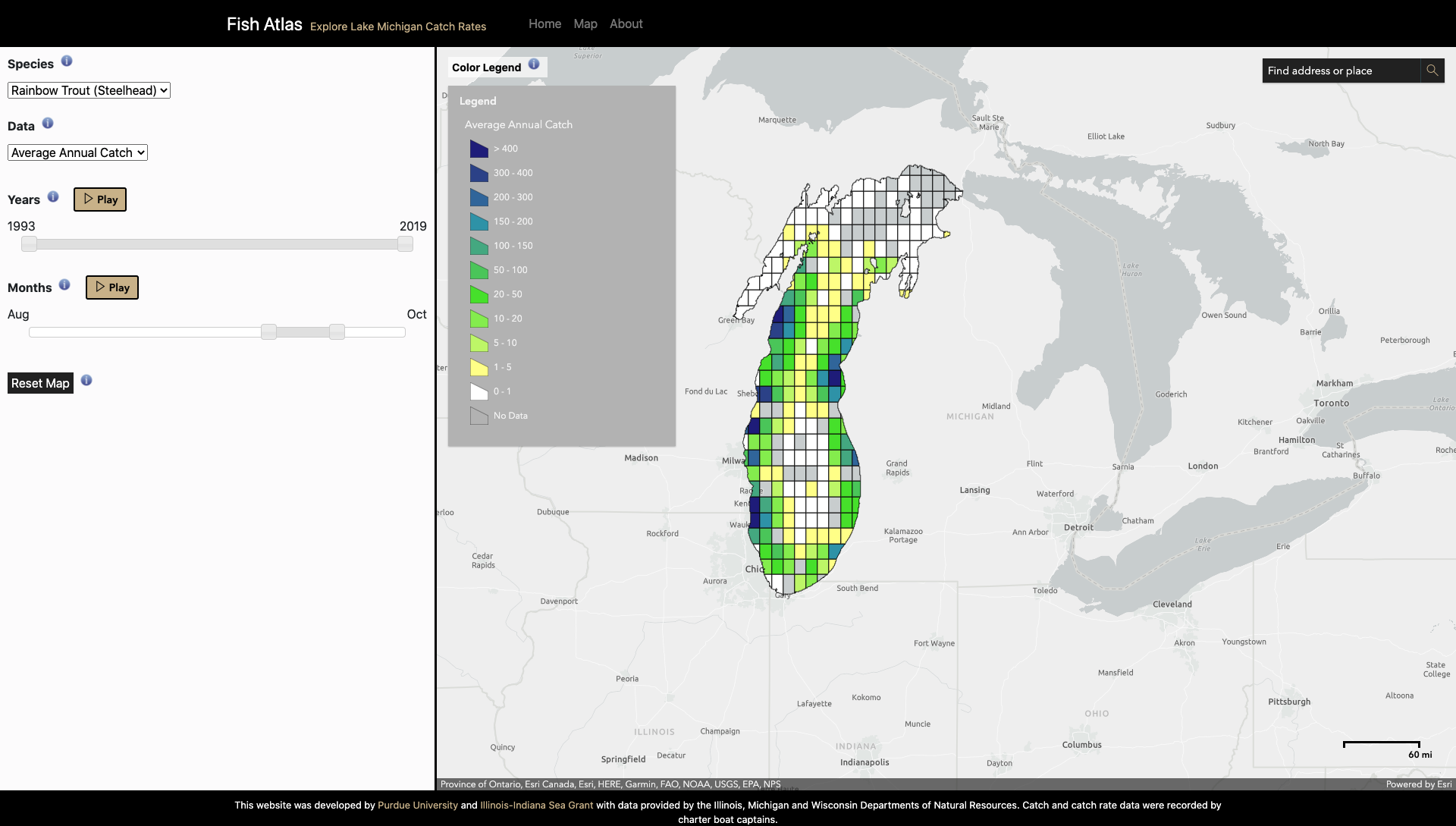

Fish Atlas is meant to help scientists, developers, land managers, fishers and anglers to look at spatial trends of five popular species: Chinook salmon, coho salmon, brown trout, lake trout and rainbow trout. It was developed in 2016 to make available to the public the historical data that has been collected by fisheries agencies, showing catch rates by location over time. Originally going back to 2012, the improved tool now incorporates data from 1993 onwards, adding 19 years of charter boat data to public access.

Developed by Mitchell Zischke of Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant and Purdue University’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, this clear and versatile method of visualizing fishing data in Lake Michigan offers a wide variety of people the chance to locate fish they might otherwise be unable to catch. Before Fish Atlas, people could request data from fishing agencies, but the information was neither publicly available nor easily accessible.

Users can now filter this historical data by species and time period. After selecting a species, the user will see a colored grid. Each square represents 10² kilometers of Lake Michigan and is color coded according to the number of fish caught there during the selected time period. Charter boats and other recreational fishing boats can use Fish Atlas to look at the lake as a whole and understand fish movements beyond just their specific launch area, allowing them to more accurately plan trips.

The revitalization of Fish Atlas has done more than improve the success of fishing trips; the partnership between fisheries and academia has been strengthened to encourage more open communication among different entities studying Lake Michigan fish. In the future, data will be updated yearly to encourage the most accurate readings. Zischke said, “If you start looking at different species and how their catch rates vary across the lake with the season, different species have quite different movement patterns.” One example of this is fish that move from being extremely concentrated in one part of the lake to spreading out over the course of an entire summer.

Beyond the direct impacts in Lake Michigan, data on species movement can be applicable to the other four Great Lakes. Salmon and trout are found in all five lakes, so learning how they move in each lake can help people understand these ecosystems more completely. Mapping tools can also be used in public engagement, which means that Fish Atlas can help increase interest in Lake Michigan among local communities—possibly connecting people to the local environment, enhancing their sense of place and desire to take care of the lake’s natural resources. Zischke hopes that the Fish Atlas data visualization project for the Great Lakes will someday be used as a model for ocean systems and movement.

In the future, Zischke hopes to enhance the visualization aspect of the current Fish Atlas model to include time series data, which would allow the user to see catch rates over time, as opposed to the current model which focuses more on catch rates through space. By combining the two, users will be able to find the most accurate data on fish migration patterns.

For those catching fresh fish this summer, Zischke recommends fish tacos garnished with local vegetables. You can find this and other Sea Grant favorites on the Eat Midwest Fish recipes page.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

Writers: Sarah Gediman, Hope Charters

Contact: Mitchell Zischke