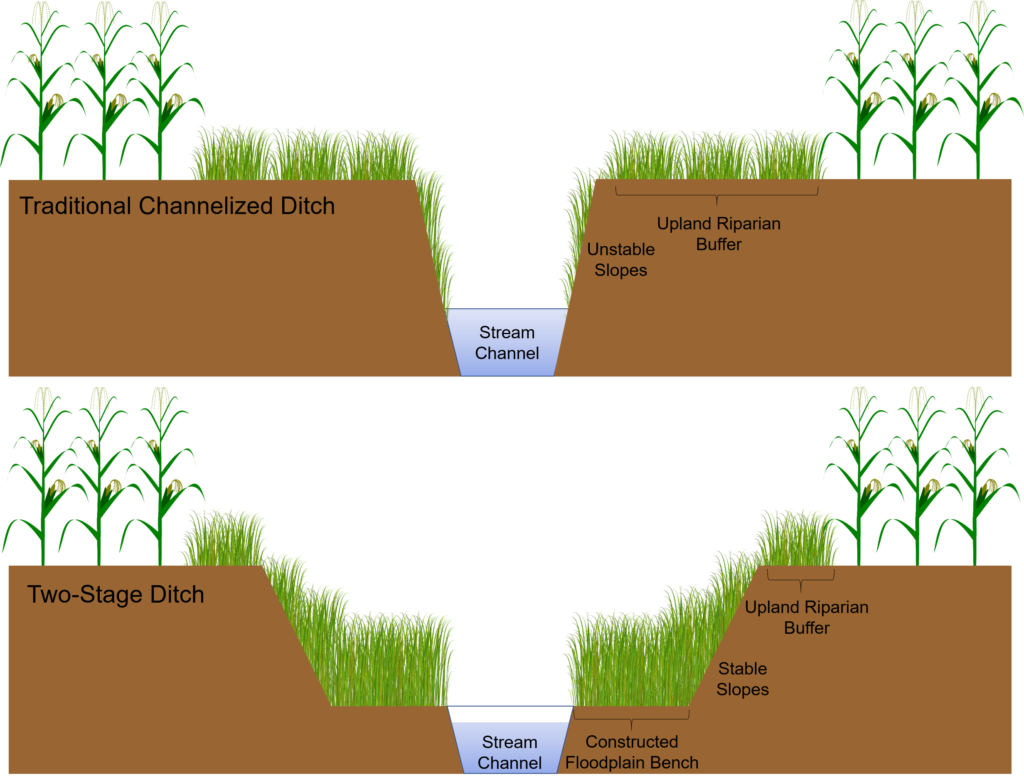

Waterways along Midwestern farmlands are typically managed to move stormwater away from crop fields quickly, but this efficient process can wash nutrients and sediment into lakes and rivers, nearby and downstream. Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant researchers have found that a change in waterway management practices can lead to a win-win—water is still quickly drained from crops with two-stage ditches, but because they have more floodplain area, stormwater slows down so more nitrogen is retained along the way.

Sara McMillan at Purdue University and Jennifer Tank at University of Notre Dame are monitoring nitrogen and phosphorus loads coming from two-stage ditches in farmland waterways to document how effective restored floodplains are at holding nutrients in place. “By restoring mini-floodplains on each side of these formerly channelized ditches, you add the potential for enhanced biology and hydrology to cleanse the water through nutrient and sediment removal,” said Tank, whose primary work is in ecology and environmental biology.

“Floodplains provide a way for water to spread out and slow down—allowing sediment to accumulate and plants and soil microbes to thrive. When plants thrive, this allows organic matter in the soil to increase,” said McMillan. In this environment, microbes use nitrogen for energy, removing it from the water as they transform it into a gas—a process called denitrification.

(Graphic courtesy of Brittany Hanrahan)

Brittany Hanrahan, whose doctoral research at Notre Dame was a part of this study, compared the effectiveness of reducing nitrogen in two-stage ditches with waterways in which traditional channelization management has stopped for at least a decade. Over time, these channels in northern Indiana developed mini-floodplains and began to look like more natural streams. The two-stage ditches in the study were about 10 years old.

Hanrahan, who now has a postdoctoral position with the USDA Agricultural Research Service, found that denitrification was 30 percent higher along two-stage floodplains compared to the naturalized ones. The two-stage ditches have more floodplain area than the naturalized channels and are designed to flood more often, which allows denitrification to happen more frequently.

“We calculated that it would take nearly 30 years for the floodplain in the naturalized ditch to accumulate the surface area of floodplain that is constructed in just one day in the two-stage ditch,” said Hanrahan. “Jump-starting the biology with two-stage construction really helps to remove more nitrogen even immediately after construction.”

While slowing down floodwater is conducive to denitrification, phosphorus goes through a different biological process. In fact, if floodwater stands long enough, phosphorus may be released from particles in the soil and water. On the other hand, creating space for water to spread out and slow down can enhance the settling of sediment particles with phosphorus attached.

The design of the two-stage ditch, including the height and width of the floodplain, can make a difference in terms of flooding frequency and duration. One general practice, according to McMillan, is to triple the width of the channel—if it is a 10-foot wide channel, 10 feet are added on either side so it is 30 feet wide.

“We’re pretty confident from previous research that it takes a long time for phosphorus to be released, so it’s not likely that we’re causing a net release of phosphorus that is stored in soils,” said McMillan, who is in Purdue’s Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering. “While we think that these ditches pose a net benefit for both phosphorus and nitrogen, phosphorus is indeed more complicated.”

Most two-stage ditches can be found in Indiana, which may be because the USDA Environmental Quality Incentives Program covers the majority of the cost of installing them in the state. It’s a one-time construction cost, whereas dredging to maintain trapezoidal channels needs to happen every few years, depending on the system. “With a two-stage ditch, the velocities in the main channel, which is the original channel, are fast enough during high flows that it is always self-cleaning,” said Tank. “You never have to dredge again.”