An IISG-funded researcher found that the mixture of pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) present in Lake Michigan can have significant negative effects on fathead minnow embryos.

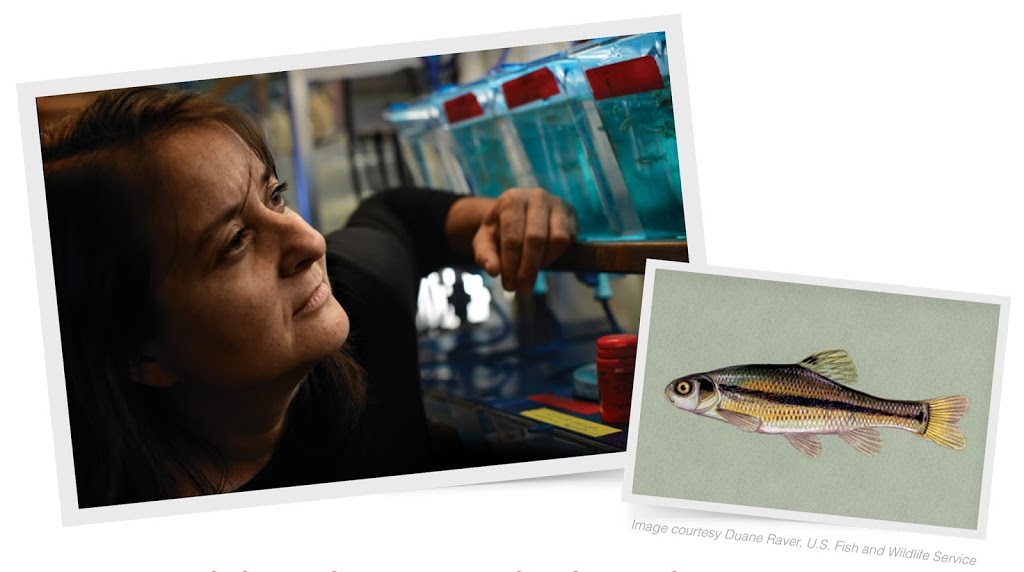

Maria Sepúlveda, a Purdue University ecotoxicologist, is telling the next chapter on research of PPCPs in Lake Michigan. In 2011, Ball State researchers, also funded by IISG, examined the concentration and detection of pharmaceuticals in the nearshore waters in Lake Michigan.Sepúlveda chose to study two of the chemicals found in that study: triclocarban, a compound found in antibacterial soaps, lotions, and toothpaste, and cotinine, a metabolite of nicotine. Both of these chemicals find their way into Lake Michigan through sewage wastewater treatment effluent.

The researchers created realistic field concentrations in the laboratory, examining effects of the chemicals both individually and in a mixture. They also examined acute and chronic toxicity of field-observed levels of chemicals on four organisms from different parts of the food chain: green algae, diatoms, zooplankton (water flea, Daphnia magna), and fathead minnow embryos.

Medicines in Lake Michigan impact minnow embryos Sepúlveda found that when she tested the four organisms with individual compounds at levels similar to those found in Lake Michigan, they remained largely resistant with the exception of the fathead minnow embryo, which was slightly affected by the triclocarban. When she exposed the organisms at the bottom of the food chain— diatoms, zooplankton, and Daphnia magna—to the mixtures, they were not affected even at high levels. Yet the hours-old fathead minnow embryo proved to be significantly susceptible to the contaminants.

“This is not surprising since embryos are known to be more sensitive to most contaminants compared to adults,” said Sepulvida. “The fish embryos were more sensitive than anything else we tested. “We chose this species because there was no data in the literature and therefore our values are novel,” she added.

Research on PPCPs in Lake Michigan and the Great Lakes overall is limited, so she cautions that these results are very preliminary. “It would be ideal if we had more data from not just Lake Michigan, but from the Great Lakes in general. But there’s just not a lot of data on pharmaceuticals from the Great Lakes right now,” Sepúlveda said.

“There are over 200 pharmaceuticals that people look for all the time in surface water. It’s overwhelming when you start thinking about it. It’s very complicated to study in a lab or in the field.”

This story appears in the latest edition of The Helm.