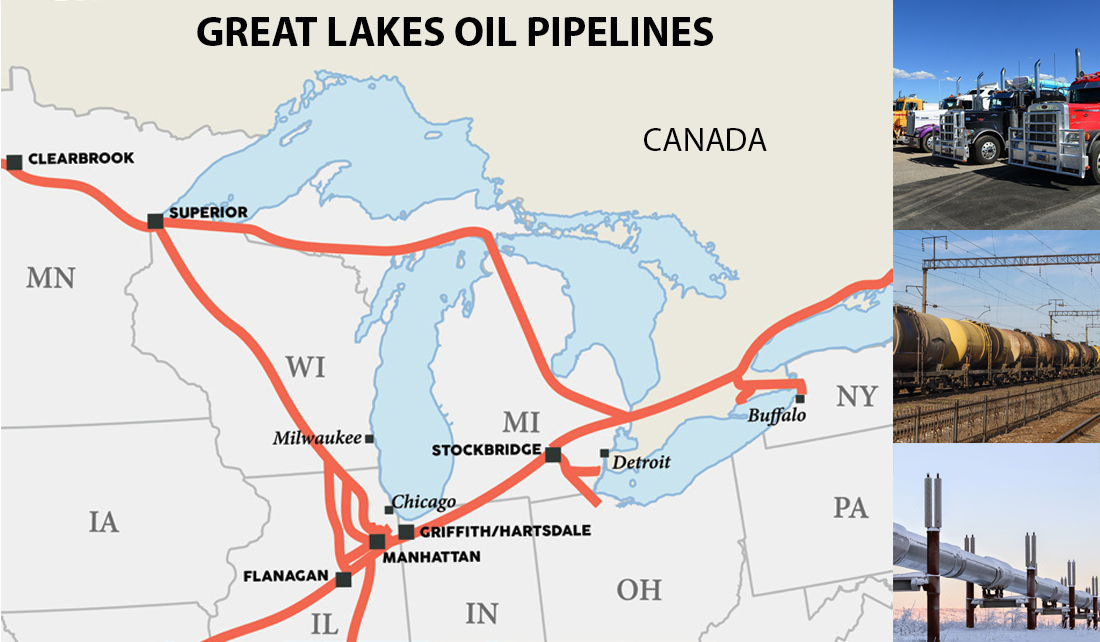

Every day millions of barrels of crude oil are piped, trucked, freighted, and shipped throughout the Great Lakes basin from the Canadian Alberta oil sands and the Bakken oil fields to refineries across the nation. This much crude oil moving around the Great lakes region is not only a challenge for transportation systems but is bringing concerns over the safety of crude oil transport front and center.

Yet crude oil is important to the region, creating economic growth in the form of jobs, industry, agriculture, and government revenue.

Last fall, the Great Lakes Sea Grant Network invited people from academia, industry, and non-profit organizations to Chicago to discuss research that would address concerns inherent to transporting this vital commodity. The goal of the resulting research agenda is to support optimal movement of crude oil throughout the Great Lakes with regards to public safety, the economy, and environmental protection of coastal resources.

“We learned that decision makers have many questions that need to be answered related to the transportation of crude oil,” said Margaret Scheneemann, IISG water resource economist and one of the meeting facilitators.

The Chicago workshop followed an initial two-day spring gathering held at Wingspread in Racine, Wisconsin, which brought a diverse set of stakeholders together to get on the same page regarding this complex issue. They reached an agreement on the primary issues surrounding crude oil movement.

“The first workshop really set the stage for subsequent dialogue,” said Schneemann. “Given that we’re going to move oil in the basin, can we work together to look at our options and identify what we need to do to better understand those options?”

For example, oil pipelines have become a hot-button issue, especially for some environmental groups and activists.

Ever since the first black gold was commercially drilled in western Pennsylvania in 1859, getting the oil to market has been a challenge. Initially the cost to transport it to the railroad was more than the oil itself was worth. So in 1865 the first reliable pipeline was built and the U.S. hasn’t stopped expanding pipelines since.

Today there is more oil than ever before traveling existing routes. Thousands of pipelines snaking through the nation move the bulk of the oil on land. Where pipelines don’t exist or aren’t sufficient, oil is moved by water, truck, or rail. In the past five years, railroads have seen a 700 percent increase in transporting oil on a system that was never meant to carry that amount.

Regardless of the method of transporting oil, incidents are bound to happen.

Dale Bergeron, Minnesota Sea Grant marine extension educator, is using his background in strategic planning and conflict resolution to encourage stakeholders to slow down and address the situation with a sound science-based, management strategy.

In addition, Schneemann will encourage stakeholders to undertake a monetary accounting of the benefits and risks so that decision makers can make apples-to-apples comparisons.

Statistically speaking, the risk is low that pipelines will fail, but one major spill can be catastrophic as residents near the Kalamazoo River in Michigan saw in 2010 when an Enbridge pipeline ruptured and caused the largest inland oil leak in the United States.

“What is the reality today and what are the impacts of various choices?” Bergeron said. “If we shut down a pipeline, it would not stop the flow of oil. It would just seek another route and perhaps a less safe one. Because refineries need stock, industry needs it, agriculture depends on it, and citizens demand it.”

This story appears in the latest edition of The Helm.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension.