“Meet Our Grad Student Scholars” is a series from Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) celebrating the graduate students doing research funded by the IISG scholars program. To learn more about our faculty and graduate student funding opportunities, visit our Fellowships & Scholarships page. Brooke Karasch is a doctoral student in the Environmental Sciences Program at Ball State University. She is currently in her third year in the program and works on research focused on the development of learning and antipredator responses. As a model for this work, she uses fish — mainly fathead minnows. In the work that’s being funded by Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, she uses lake sturgeon. Her broader research interests focus on how behavioral ecology can be used to further conservation goals.

This lake sturgeon is about 2-3 weeks old. It’s developing the characteristic snout and the sharp scutes, or protective scales, in a ridge along its back. Although this sturgeon was less than 2 inches long at the time, adult lake sturgeon can reach 7 feet.

Have you ever thought about how an animal knows which other animals it should be afraid of? Probably not, but this kind of question is what Brooke Karasch thinks about all day in her PhD research. The Ward Lab at Ball State University—where she conducts her work—focuses on a few different areas of animal behavior, including the effects of pollution on behavior, the sensory inputs that affect behavior, and most interestingly for her, the early life development of learning. In her work as an Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant Grad Student Scholar, Brooke is focused on how lake sturgeon learn to recognize and respond to a predator at their earliest life stages.

Before this research could begin, Brooke needed one key component: lake sturgeon gametes. To procure lake sturgeon sperm and eggs, she worked with collaborators at the Black Lake Sturgeon Facility. The team of fisheries technicians ventured out to the Black River beginning in late April. Divers donned wetsuits and snorkels, and returned to the surface with over 250 adult sturgeon over the course of the breeding season. Not all of them were ready to breed at the time of capture, but by early May, they’d collected gametes from 8 adult males and 8 adult females for Brooke, and other researchers, to use. (All sturgeon were released unharmed!)

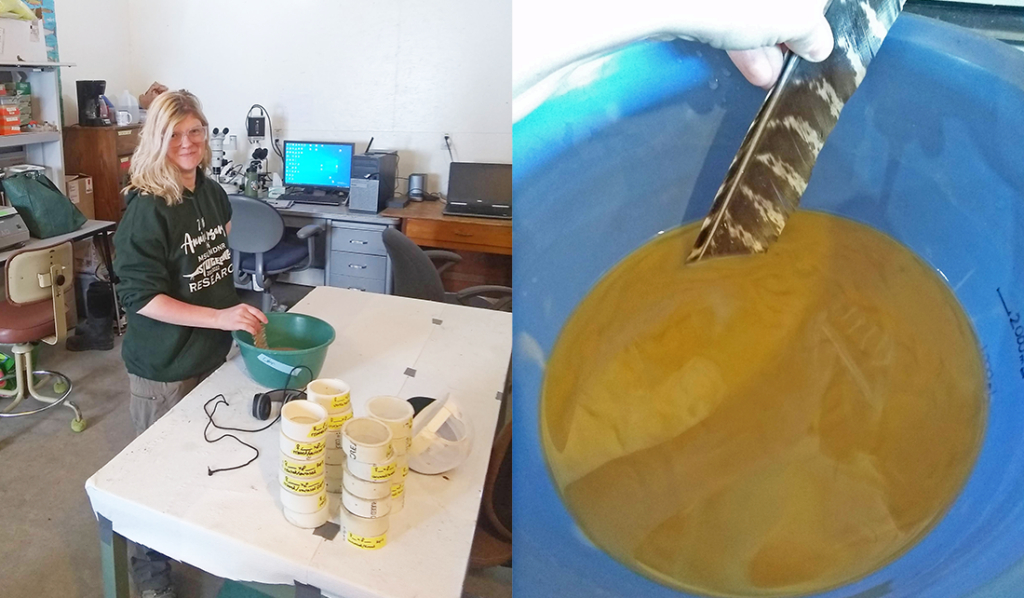

Lake sturgeon are broadcast spawners, which involves the release of both eggs and sperm into the water column, so a given female’s eggs might be fertilized by sperm from many different males in the wild. However, for research purposes, it’s useful to know who the parents are. So, upon bringing the male and female gametes to the lab, they were hand-fertilized using a technique that the Black Lake facility developed — carefully stirring the eggs and sperm in a concoction of clay and water, using a turkey feather. The clay is to prevent the embryos from sticking together, which can make them more susceptible to disease. The feather is used to gently keep them in motion while the clay coats them.

After collecting eggs and sperm from adult lake sturgeon in the Black River, Karasch fertilized them manually. The process is a little strange: eggs and sperm are swirled together, then rinsed, then stirred in a clay mixture for nearly an hour. The clay prevents the eggs from sticking together, which improves survival. She used turkey feathers to stir the eggs because they’re delicate, and the feather is gentle. Finally, she rinsed them with iodine before setting them up in treatments, to help prevent any early infections the eggs might pick up from river water.

Once the eggs were fertilized and began developing as embryos, the experiment began in earnest. Brooke’s work focuses on learning in fish, when they are at the earliest life stage, which is the embryonic stage. What would an embryonic fish need to learn? There is one critical piece of information that all animals need to know at every life stage: which animals are likely to eat them. To teach embryonic fish about predators, Brooke uses associative learning, similar to Pavlov ringing the bell at the same time as he fed the dog, until the dog associated the bell with food.

Brooke presented the sturgeon embryos with two scent-based cues. One was an “alarm” cue, which the sturgeon embryos innately recognized as dangerous; the cue was made of naturally deceased juvenile sturgeon, pulverized and diluted with water. The other was a “predator” cue, which the sturgeon embryos had to learn was dangerous; this cue was made from water that rusty crayfish were kept in for 24 hours.

The embryos were given both cues together from the time they were first fertilized until they began hatching. But there was another twist to this experiment — Brooke also wanted to know how temperature would affect learning for the embryos. Throughout their development, she kept them at three different temperatures: 58°F; 65°F; and varied from 54°-72°F, depending on the river itself. The information gained through varying temperatures is meant to help Brooke investigate how climate change might affect learning in this imperiled species.

Just before the embryos began hatching, Brooke started experimental tests. To determine if they would use their antipredator behaviors without the alarm cue, she tested them in either plain water or water with only the predator cue. This would show if they had learned to associate the predator cue with the alarm cue. First, she tested embryos. Because embryos are inside an egg and are surrounded by the eggshell (called the “chorion”), the antipredator behavior is to hold still and cease movement since they can’t swim away. Normally, embryos wiggle around a little inside their chorion, but if they detect a signal of “danger” such as the scent of a predator, they’ll hold still to hopefully avoid being seen. After completing test on the embryos, Brooke then let them hatch and tested them again a few weeks later.

“Analysis is ongoing, so it’s hard to say just yet what the results of this experiment might be,” said Brooke. “I’m excited to keep digging into the data for the project. This research will provide more information on how learning develops, and it’s especially important to get this kind of information for an imperiled species like the lake sturgeon.”

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a partnership between NOAA, University of Illinois Extension, and Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources, bringing science together with communities for solutions that work. Sea Grant is a network of 34 science, education and outreach programs located in every coastal and Great Lakes state, Lake Champlain, Puerto Rico and Guam.

Contact: Carolyn Foley