Meet Our Grad Student Scholars is a series from Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) celebrating the students and research funded by our scholars program. To learn more about our faculty and graduate student funding opportunities, visit Fellowships & Scholarships.

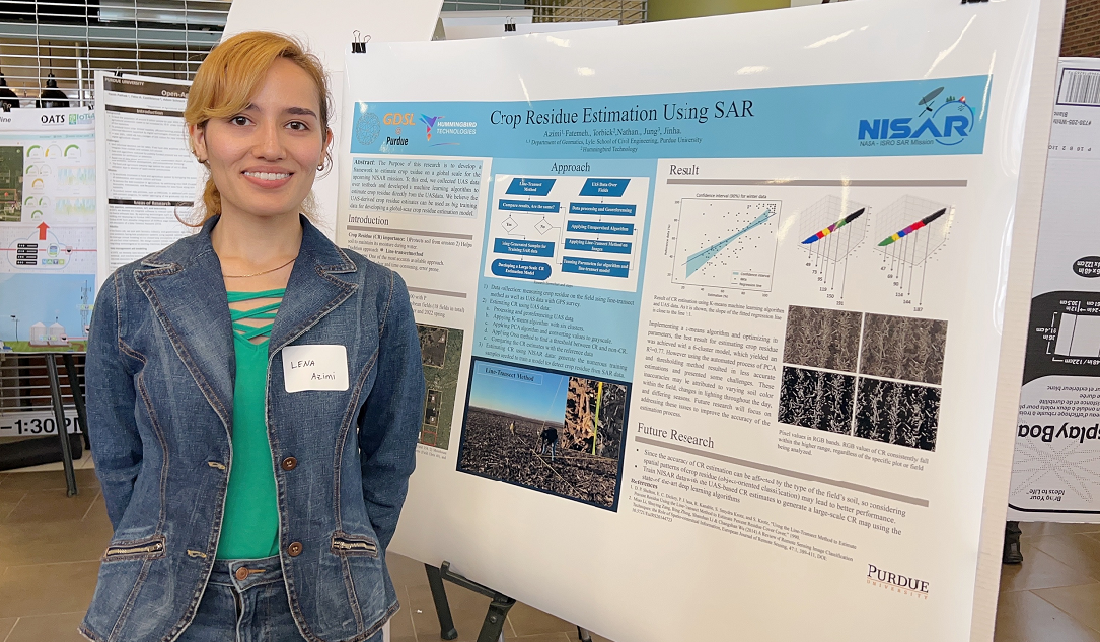

Lena Azimi is a fourth-year Ph.D. student in the School of Civil and Construction Engineering at Purdue University, specializing in geomatics with a background in environmental engineering. During her master’s program, Azimi encountered remote sensing technology, which provides a way to collect data from a distance, especially remote or hard-to-reach places. This experience led her to pursue a Ph.D. degree and dive deeper into remote sensing and tackle urgent environmental challenges.

My current research focuses on using synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data to estimate soil moisture with finer spatial and higher temporal resolution. Measuring soil moisture is a big deal for water resource management, irrigation scheduling, and even forecasting floods and wildfire risk assessment.

Sustainable agriculture hinges on knowing how much water is in the soil. Too little, and crops suffer. Too much, and you risk diseases, soil salinity, and wasted resources. With more precise soil moisture information, farmers can fine-tune irrigation schedules, boost yields, and save money.

Soil moisture data isn’t only about agriculture. It’s a critical input for flood forecasting. When soil is already saturated, it can’t absorb much more water, making flooding more likely. Knowing soil moisture also helps predict wildfire risks, track droughts, and support ecology research. The broader water resource management stakeholders include governments, NGOs, and industries that need reliable, high-quality data to make informed decisions. I hope that by improving these estimates, we can give decision-makers a powerful tool to plan for both current climate realities and future uncertainties.

Soil moisture measurements may sound simple, but it is a challenging problem due to the complexity involved in the phenomenon. While in-situ sensors can accurately measure soil moisture, they have limited spatial coverage and don’t always capture how much soil moisture can vary across different areas. In addition, the in-situ sensors need frequent maintenance and calibration. That’s where remote sensing steps in—offering a broader view and consistent data collection across wide regions.

SAR, in particular, provides data in nearly all weather and lighting conditions, making it ideal for soil moisture estimation. However, the existing models we use to convert raw radar data into soil moisture metrics often miss the mark compared to ground truth measurements. By refining these models, I hope to contribute more accurate and higher-resolution soil moisture estimates that can benefit many stakeholders, from farmers to policymakers.

My Ph.D. research focuses on improving soil moisture estimation methods, particularly in water-scarce regions. One exciting development is our use of drone-based SAR for ultra-high-resolution data. Drones can fly low, capture fine details, and offer a level of control that satellites can’t match. That means farmers and resource managers could one day receive near-real-time, high-quality data to inform water use, benefiting their bottom line and the environment.

Handheld soil moisture probe used for ground reference soil moisture data collection – June 2024

To get the best results, we collect data from multiple angles – four flights around the field. We use SAR, LiDAR, and RGB imagery. LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) helps us measure soil roughness and gather structural information on crops. RGB (red, green, blue) imagery provides familiar, photo-like images. And, of course, we gather on-the-ground reference soil moisture data using handheld probes or permanently installed sensors.

Combining all these data demands an interdisciplinary mindset and a willingness to juggle different file formats, sensor limitations, and analysis techniques. But the payoff is huge: a clearer, more nuanced picture of how soil moisture changes over time and space.

As much as I love my research, I’m equally passionate about teaching and mentoring. I’ve worked as a teaching assistant for courses like Principles of Geomatics and Surveying, as well as Environmental Hydrology. There’s nothing quite like watching a student’s face light up when they grasp a new concept.

Collecting data in the Pinney Purdue Agricultural Center fields at the Agronomy Center for Research and Education.

I also mentor undergraduate students, helping them discover research topics, formulate questions, read scientific literature, dive into coding, and interpret their findings. My approach is scaffolding I guide them early on, then step back to let them learn independently. The ultimate goal is to instill confidence and competence, helping them become researchers in their own right.

My journey combines environmental sustainability, remote sensing, and education, and I believe these fields can unite to address global water challenges. By refining soil moisture estimation, collaborating with experts in other disciplines, and nurturing the next generation of scientists and engineers, we can protect our planet’s water resources and improve the quality of life worldwide.

I’ve shared some snapshots of our data collection adventures and the fun moments we enjoy in the Geospatial Data Science Lab (https://gdsl.org).