I’m aboard a 180-foot research vessel traversing Lake Huron; the ship is the U.S. EPA R/V Lake Guardian, and the goal is to take the pulse of this gaping freshwater entity. Every year the Cooperative Science and Monitoring Initiative (CSMI) comprehensively surveys one of the five Great Lakes. As a result, it’s been five years since we’ve taken a long look at Lake Huron.

Those working on this particular six-day research cruise vary from marine technicians who live on the ship for the whole sampling season, to scientists from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) onboard for the week to collect data and bring it back to their labs.

Left: A larval fish seen under a microscope. Right: The trawl net used to sample larval fish being pulled in over the sunrise.

And me?

I’m here with IISG as the Great Lakes communication and outreach intern, helping out with the sampling and observing so that when I’m back on land, I can use this experience to enhance my translations of scientific studies from the 2015 CSMI survey of Lake Michigan to engaging, accessible outreach materials for policy makers, fisheries managers, and the general public.

Clark working on the fantail.

I am on the 4 a.m. to 4 p.m. shift of this around-the-clock undertaking. At 3:30 a.m., I’ve got to hastily get up and shuffle down the hall to relieve the night shift on the back deck. I pull on my rain boots, life jacket, and hardhat, then grab a clipboard to record the samples as they come in. There are six sampling sites to complete on this cruise, and each composes a “transect,” a narrow section of water which runs perpendicular to the shoreline, providing an offshore, mid-shore, and nearshore snapshot.

Each station has a sampling agenda. If a station is reached at night, this protocol begins by sampling benthic, shrimp-like animals known as Mysis under red light. If the sun has already risen, we use an extremely large and well-outfitted CTD—an instrument that measures conductivity, temperature, and depth as it is deployed through the water column.

Next up is the zooplankton sampling, followed by two ichthyoplankton tows to sample larval fishes—the early stage in a fish’s life history where they are mere millimeters in length, floating about eating the zooplankton we sampled just prior. The larval fish collected are separated from the various bycatch of flotsam and examined back at USGS headquarters for a variety of parameters including species, length, and age.

The age data, collected by examining growth increments on the larvae’s minute otoliths (inner ear bones), is reported in days old. I find them enormously cute, in an E.T.-without-legs kind of a way.

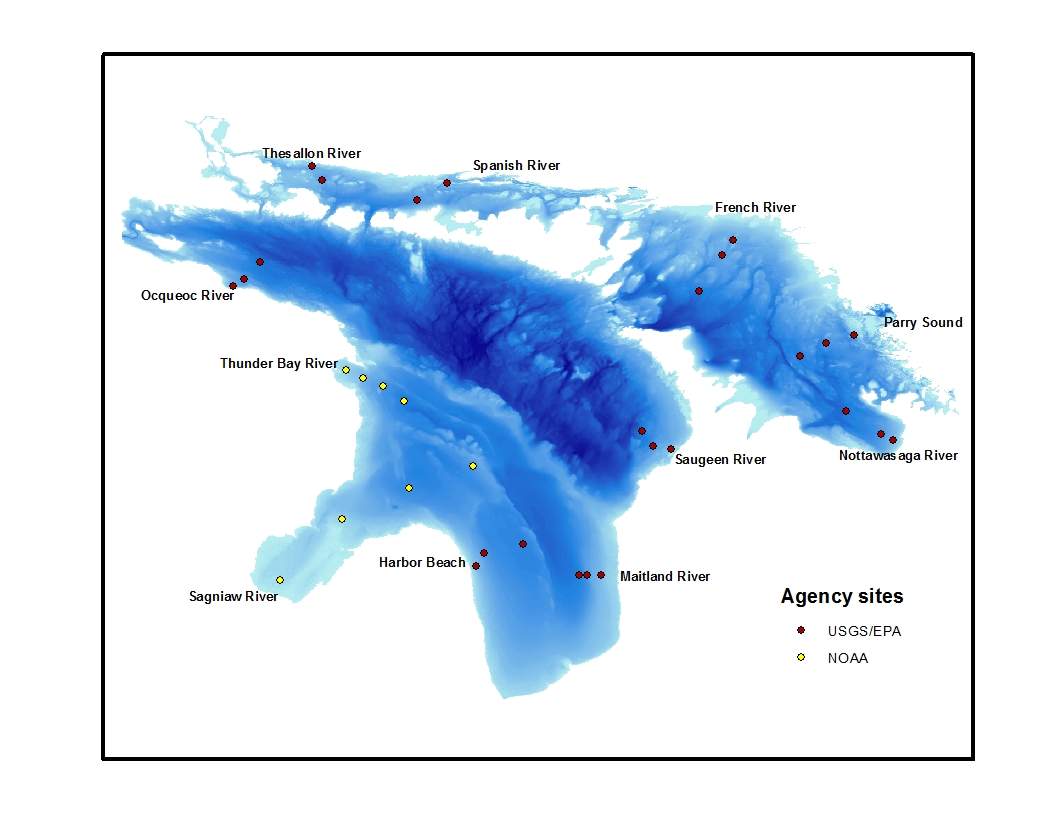

Map of the CSMI survey stations in Lake Huron. During this cruise Harbor Beach, Maitland River, Saugeen River, Nottawasaga River, Parry Sound, and French River transects were sampled, in that order.

After each of the three stations have been surveyed, a large sampling instrument called the Triaxus is towed back along the entire transect to gather information across the full survey area. Depending on the length of the transect, this can take a while.

I have found this a great time to hit the galley and grab a second or third breakfast, depending on the day. After all, by 9 a.m. I’ve been awake for a good five to six hours and there’s more sampling to do.

We then lower the Rosette, a big water sample collector, to measure the amount of chlorophyll in the water. We also put nets down six different times to collect zooplankton. We then used a big net to collect larval fish out the side or behind at different depths throughout the water column. We also towed the Triaxus for a few hours. We head to the next transect and do it all over again.

And—if we’re lucky—in exchange for all our hard work, the next time I crawl out of my bunk at 3 in the morning I get to witness a scene like this one:

Emily Clark is working with Paris Collingsworth and Kristin TePas as a summer intern with IISG where she is creating outreach materials for the results of the 2015 Lake Michigan CSMI field year. Clark is a student at College of Charleston in South Carolina studying biology, environmental studies, and studio art.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.