July 7th, 2023 by Carolyn Foley

Meet Our Grad Student Scholars is a series from Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) celebrating the graduate students doing research funded by the IISG scholars program. To learn more about our faculty and graduate student funding opportunities, visit our Fellowships & Scholarships page. Emma Donnelly is a master’s student in the School of Environmental Sustainability at Loyola University Chicago. Her thesis research is focused on residential mobility and the value of water quality restoration in Great Lakes Areas of Concern.

For decades, legacy pollutants from historical industrial activities have created health concerns for residents in the Great Lakes region. High costs are often a burden in the cleanup process and become a continuous obstacle in tackling water quality issues that affect residents and wildlife. Loyola student Emma Donnelly is conducting research that provides promising insights into the economic benefits of investing in remediation of heavily polluted locations around the Great Lakes. Cleaner water and healthier ecosystems have the potential to expand opportunities for development and recreation, while enhancing local economies and wildlife habitats.

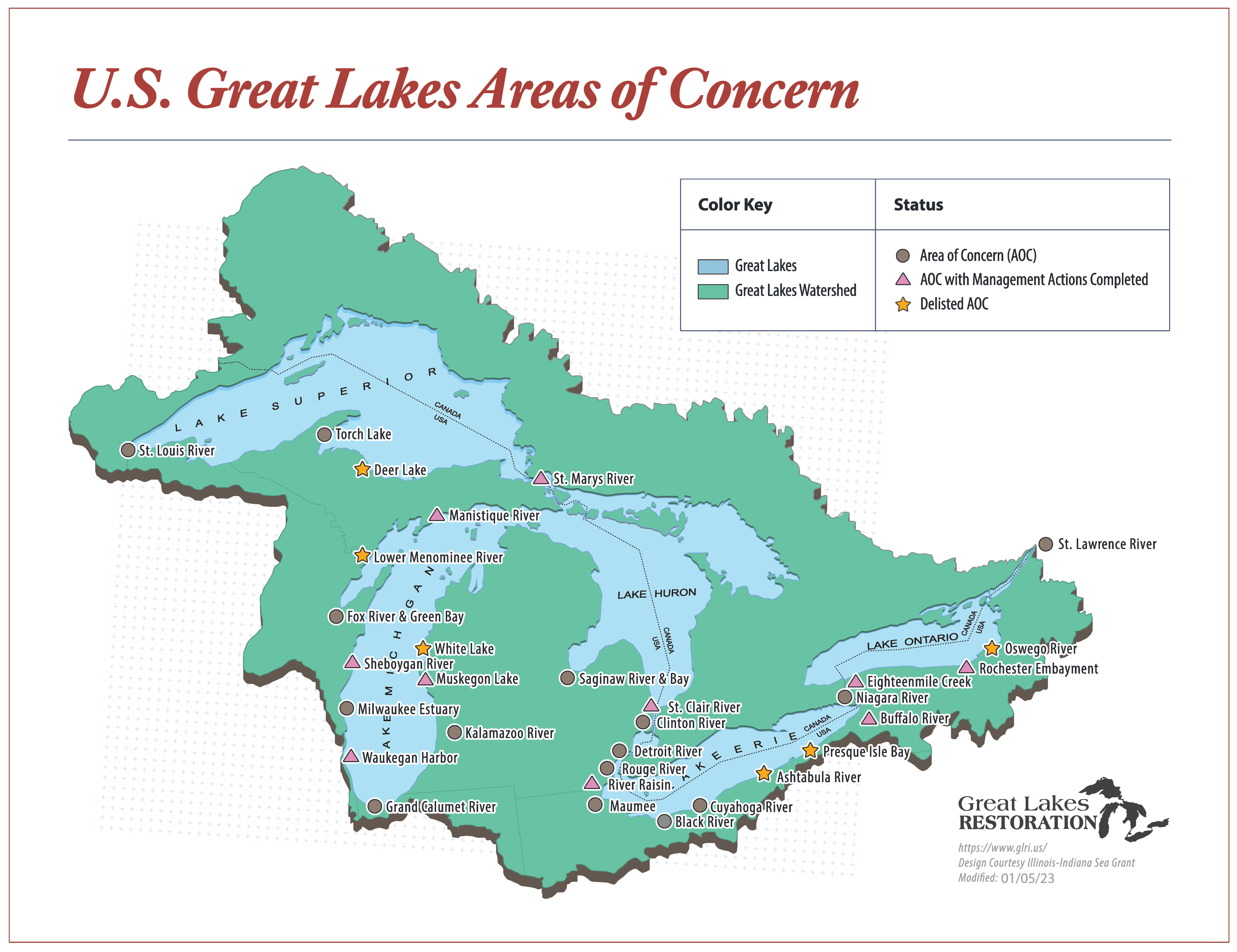

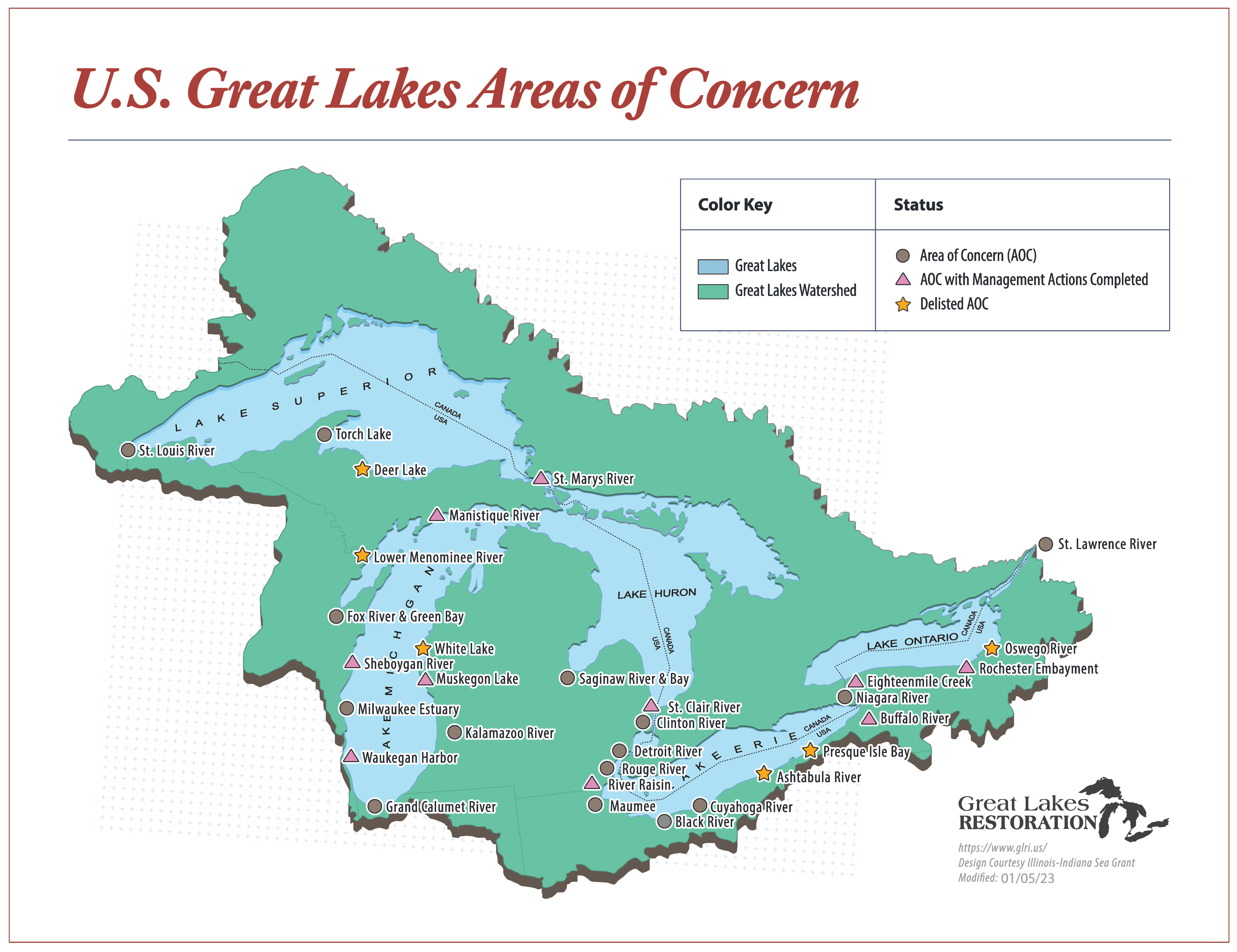

Location and status of the U.S. Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Updated January 5, 2023.

Legacy pollutants, well-known industrial substances, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), not only create health concerns for communities but also threaten the wellbeing of wildlife and limit recreational activities and development of coastal areas. In 1987, the United States and Canada established the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement in an effort to address concerns about legacy pollutants in the region. This agreement established Great Lakes Areas of Concern (AOCs) to be prioritized for cleanup. Between 1985 and 2019, the United States and Canada spent $22.78 billion restoring AOCs. This has prompted people to ask questions such as: Do the benefits of cleanup outweigh the costs? Might additional cleanup be worth it? Answering questions like these is essential to evaluating the cost-effectiveness of the AOC program.

Waukegan Harbor. Image source: https://www.visitlakecounty.org/WaukeganHarborandMarina.

Waukegan Harbor in northeastern Illinois is one of the 43 AOCs designated through the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. Legacy pollutants were first discovered in the harbor in 1975. Since its listing as a Superfund site in 1981 and designation as an AOC in 1987, the Waukegan Harbor AOC has undergone significant remediation. It currently holds the status of “Management Actions Complete,” meaning that all cleanup projects have finished and the AOC is being monitored for delisting.

Over $73 million has been invested in contaminated sediment remediation in Waukegan Harbor. Measuring the economic effects of restoration is essential to understanding the consequences of remediation. In many AOCs, there is a stigma associated with contamination of the water, so remediation of the harbor could contribute to new economic activity in downtown Waukegan. The harbor provides a space for employment at industrial facilities as well as recreational opportunities at public parks and beaches on Lake Michigan, and access to these uses—resulting in economic benefits to the city—can be improved through cleanup.

The goal of Emma Donnelly’s research is to estimate the economic value of restoring the Waukegan Harbor AOC. Her methodology uses an analysis of house sales in Waukegan before and after several milestones of cleanup progress. The analysis relates home prices to property characteristics, including proximity to the boundaries of the AOC. Specifically, in her study, Donnelly examines the effect of the removal of Beneficial Use Impairments (BUIs) on home values. BUIs are water uses that have been restricted because of pollution (e.g., restrictions on recreation and consumption of fish). An AOC is delisted once all of its BUIs have been removed. In the Waukegan Harbor AOC, five BUIs were removed between 2011 and 2020. Only one BUI has yet to be removed—restrictions on fish and wildlife consumption—although it is expected to happen by 2026.

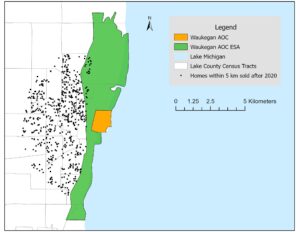

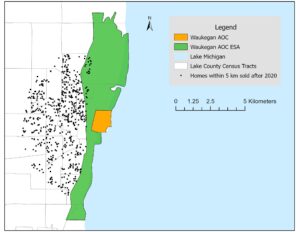

Map of the Waukegan Harbor Area of Concern (AOC) and Extended Study Area (ESA), plus locations of nearby homes that have been sold since 2020.

Donnelly’s analysis provides evidence that local residents value the cleanup of the Waukegan Harbor. The results of the hedonic analysis of Waukegan Harbor indicate that home prices increased by $12,832 per household, or $169 million in aggregate for all households within five kilometers of the AOC.

Donnelly also finds the benefits of the cleanup only emerged after the fifth BUI was removed, suggesting that substantial cleanup may be required before benefits capitalize into housing prices. Her results indicate that the benefits are concentrated in homes approximately 1 to 3 kilometers from the harbor, and that benefits decrease with distance from the harbor. This is consistent with prior research that suggests that the benefits of cleanup diminish for homes that are far from the site of cleanup. She believes one reason why she does not find benefits for homes within one kilometer could be because of the nearby industrial area, highway and railroad surrounding the harbor, which separates homes from the immediate vicinity of the AOC; in fact, there are very few homes located within one kilometer of the harbor. Also, other location characteristics that are part of the industrial setting could have lessened the effect of the cleanup on home prices. Overall, Emma’s findings may suggest that for industrial areas with degraded water quality, where households are not located immediately adjacent to the water, substantial progress toward full restoration may be required before benefits start to capitalize in home values.

Sources:

Thirty-five years of restoring Great Lakes Areas of Concern: Gradual progress, hopeful future – ScienceDirect

Waukegan Harbor AOC | US EPA

Waukegan Harbor Remedial Action Plan. Final Stage III Report – Waukegan Harbor RAP – July 1999

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a partnership between NOAA, University of Illinois Extension, and Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources, bringing science together with communities for solutions that work. Sea Grant is a network of 34 science, education and outreach programs located in every coastal and Great Lakes state, Lake Champlain, Puerto Rico and Guam.

Contact: Carolyn Foley

November 27th, 2017 by IISG

Legacy pollutants—chemical contaminants left behind by industry from decades ago and prior to modern pollution laws—remain a burden in some Great Lakes communities. In fact, the U.S. side of the Great Lakes have 27 Areas of Concern (AOC) that are still considered impaired due to risks to human health, pollution, habitat loss, degradation and other issues.

“For the first time, we have a program and funding specifically dedicated to addressing the most pervasive environmental problem facing the AOCs,” said Matt Doss, policy director for the Great Lakes Commission. “Not only has the Legacy Act lead to actual cleanups of contaminated sediments—generating real, on-the-ground environmental improvements—it revitalized the entire AOC program by demonstrating that real progress was possible.”

Over multiple projects, nearly 1 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment in the Buffalo River have been cleaned up through the Great Lakes Legacy Act.

The GLLA program is administered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Great Lakes National Program Office in Chicago, Illinois. GLLA uses a unique funding strategy that combines voluntary support from states, businesses, and non-governmental organizations, and the federal government through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant assesses outreach needs and engages stakeholders at the community level where GLLA sediment cleanups take place.

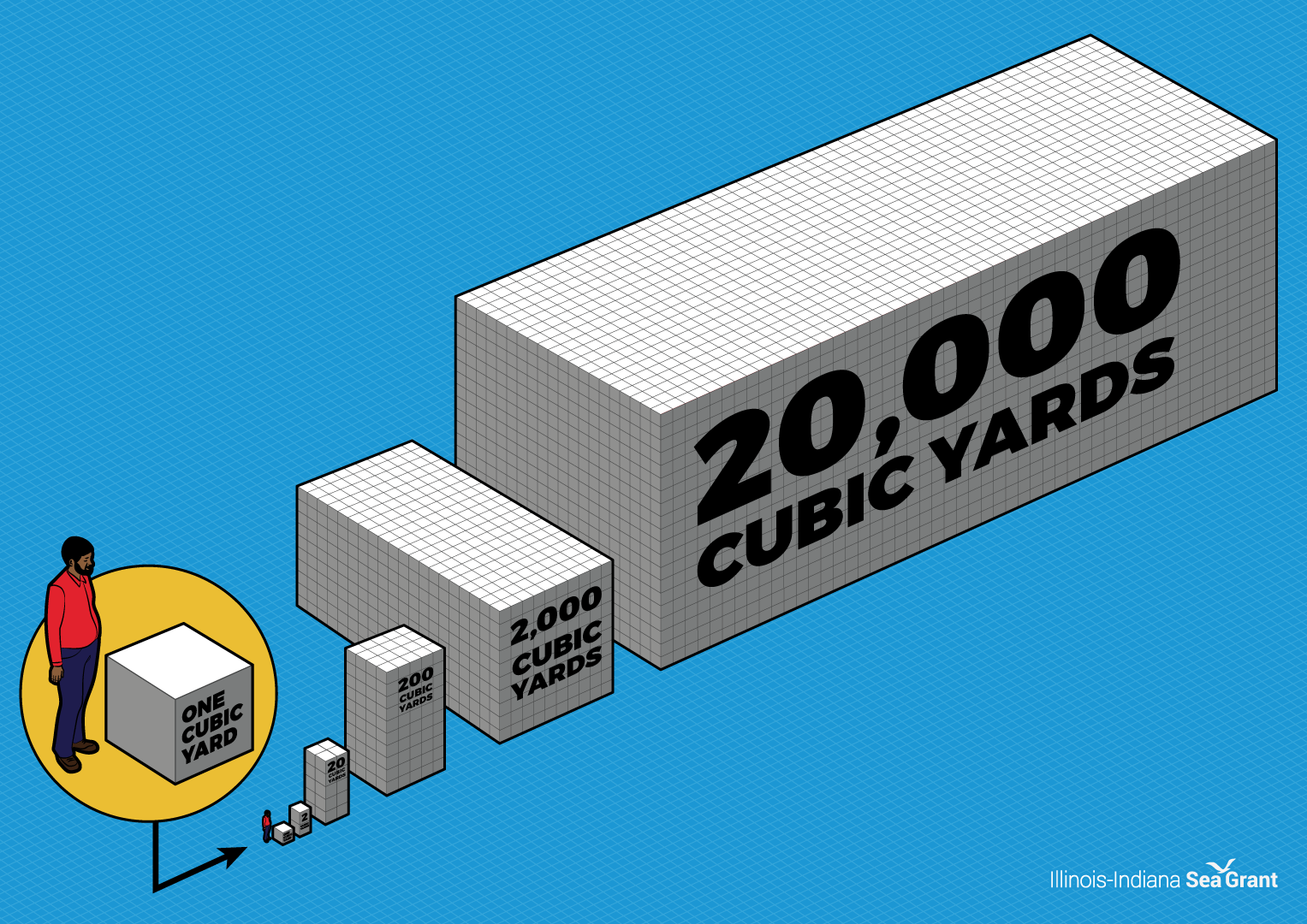

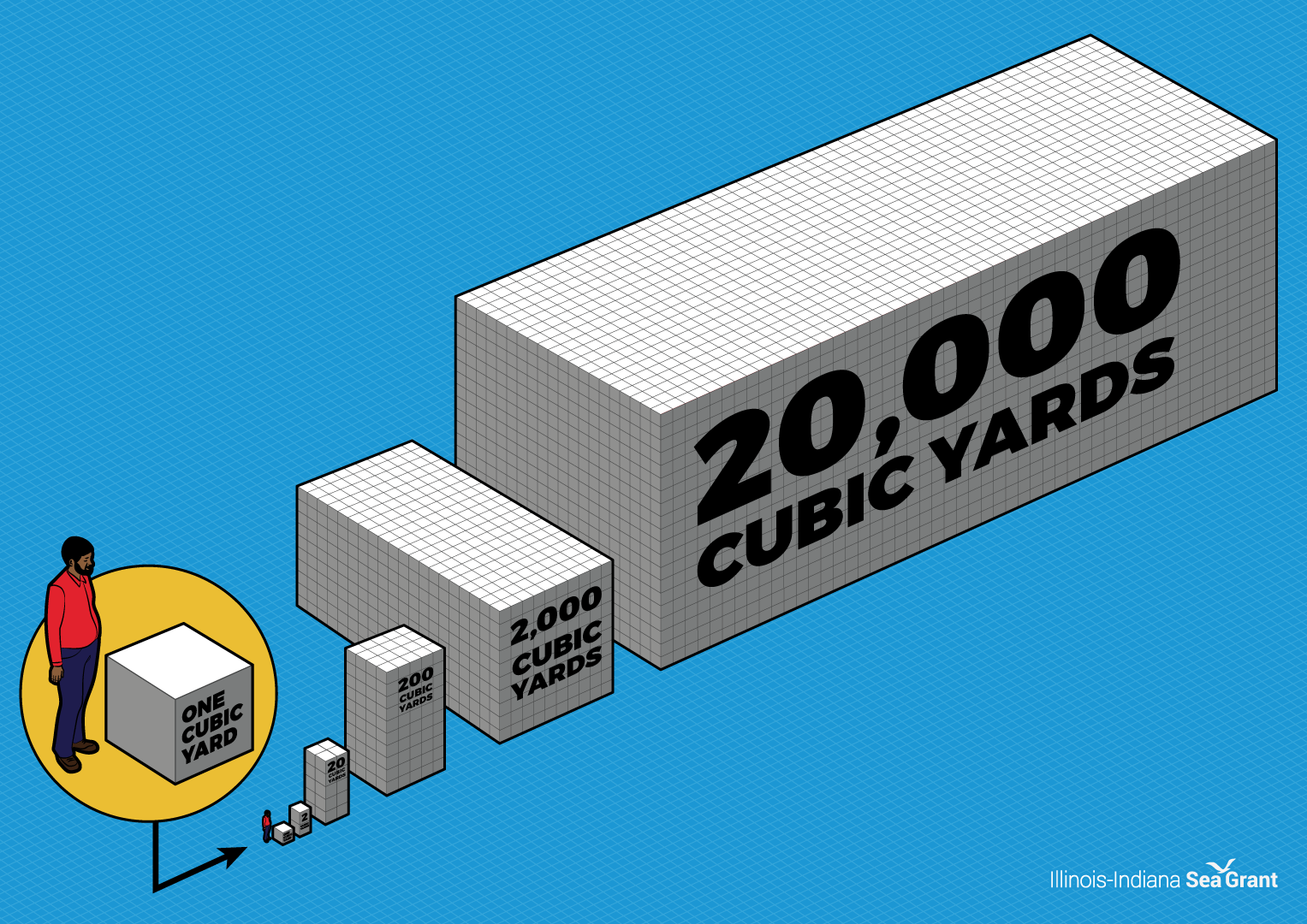

Sediment cleanups come in many sizes. The largest GLLA completed project dredged and capped one million cubic yards of contaminated sediment from the East Branch of the Grand Calumet River in northwest Indiana.

“Together, the State Natural Resource Trustees, Federal Natural Resource Trustees and EPA have spent over $180 million on sediment remediation projects in the Grand Calumet River, supporting a heathier fish community and attracting a robust migratory bird population,” said Bruno Pigott, Commissioner of the Indiana Department of Environmental Management.

To put dredge volumes in perspective, consider how the size of a single cubic yard compares to the average height of a man.

Much has been accomplished in the program’s first 15 years. Under GLLA, 21 projects are complete in six out of eight Great Lakes states, and more are in the planning stage. Through federal support and local funds, over $588 million has been spent to investigate sediment contamination, design cleanups, and implement solutions to pollution in AOCs.

“The Legacy Act is now among the most successful cleanup programs in the region and a cornerstone of the AOC program,” said Doss.

For the most comprehensive web coverage of sediment cleanups under the Great Lakes Legacy Act, visit www.greatlakesmud.org or follow Great Lakes Mud on Facebook.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

October 12th, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

Lincoln Park and I are both coming to the end of an exciting chapter this fall. As my internship with

IISG comes to a close, Phase 2 sediment remediation work in in Lincoln Park in Milwaukee is also finishing up.

Four years and more than 170,000 cubic yards of contaminated sediment later, Lincoln Park is looking to reap the benefits of the newly cleaned Milwaukee River. As contractors work to remove equipment, sediment samples are being taken to ensure no contamination has been missed.

To commemorate this truly historic milestone, IISG environmental social scientist

Caitie Nigrelli and I traveled to Milwaukee to spend some time on the river and celebrate the success with our clean-up partners. Hospitable as usual, Friends of Lincoln Park members took us around the city allowing us to catch a glimpse of the possibilities that environmental reinvestment holds for community revitalization.

Within the park, we took advantage of the warm fall weather for a canoe trip through the remediated portion of the river. As we paddled, perennial grasses and beaver-cut branches secluded us from Lincoln Park’s urban setting. We were not the only ones out experiencing the newly restored park; kill-deer, great blue herons, and other wildlife were also enjoying a clean habitat.

Although remediation work is complete, there is still much to be done within the park. Much like sediment remediation, successful ecosystem restoration is a long process. Started in 2012, the 11-acre Phase 1 restoration work is finally showing the fruits of its labor.

Many bees could be seen buzzing around native asters (see photo) and goldenrod on the shoreline at the west end of the park. Like Phase 1, restoration work in the East Oxbow of the river will bring a diversity of native plant species, stabilize the shoreline, and provide habitat for fish and wildlife.

After watching the sun set over the river, Caitie and I completed our day at the

Friends of Lincoln Park restoration celebration. Over cake and ice cream, representatives from the Milwaukee County Parks and CH2M, an environmental consulting company, presented information on the remediation and restoration progress.

The neighborhood unity fostered through this river cleanup is impressive. As a new chapter begins for the river, park, and neighbors alike, seeds of passion and park investment are spreading, akin to the native seeds of restoration to come.

-Carly Norris

April 29th, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

Over 200 bags of trash, some shopping carts, mattresses, and a port-o-let were removed from Milwaukee’s Lincoln Park earlier this month during an annual river cleanup led by Milwaukee Riverkeeper. The event drew nearly 3,500 residents and local officials to rivers across the city. Almost 100 of these volunteers were members of the Friends of Lincoln Park. Formed last October, this cleanup was the group’s first outreach project, with many more slated for 2015.

Members of the Lincoln Park community first came together in response to ongoing efforts to rid the Milwaukee River bottom of legacy contaminants like PCBs and PAHs. Phase two of the Great Lakes Legacy Act project was underway, and with the river making up such a large portion of the park, the community was taking notice. With support from focus groups conducted by Caitie McCoy and UW-Extension’s Gail Epping Overholt, residents were inspired to create a way to voice their thoughts and concerns on the direction of the park.

The result was the Lincoln Park Friends Group, who, in association with Milwaukee County Parks, the Park People, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, and Wisconsin Sea Grant, is now working to revitalize Lincoln Park in a way that brings together the surrounding community.

The result was the Lincoln Park Friends Group, who, in association with Milwaukee County Parks, the Park People, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, and Wisconsin Sea Grant, is now working to revitalize Lincoln Park in a way that brings together the surrounding community.

“Most members have grown up enjoying the parks,” said David Thomas, secretary for the Friends of Lincoln Park. “We all think of the parks as a valuable community resource.”

The group hopes to instill a similar sense of stewardship in other community members. Along with plans to clear out areas overgrown with invasive plants, some members have expressed an interest in creating youth groups to provide opportunities to learn how to fish or canoe and to get to know the park’s natural surroundings in general.

“There’s a ton of work to do, but we want to build organically,” Thomas added. “We want to build it slowly, and we want it to be strong and sustainable.”

***Photo credit: Friends of Lincoln Park

April 23rd, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

A closer look at web tools and sites that boost research and empower Great Lakes communities to secure a healthy environment and economy.

Residents living near sediment remediation projects can now stay up-to-date on cleanup goals and milestones with GreatLakesMud.org. Developed by IISG, this comprehensive site provides information on waterways selected for cleanup and restoration through the Great Lakes Legacy Act.

At the heart of Great Lakes Mud are site-specific pages that identify contaminants of concern and outline plans for cleanup and habitat restoration. Here, visitors will find the latest on dredging schedules, truck routes, opportunities for community involvement, and more.

The website also provides insight into how Legacy Act projects are chosen and designed and explains how cleanup strategies like dredging and capping are able to remove the dangers of contaminated sediment while improving aquatic habitats.

Illustrative photos and videos bring these processes to life and help viewers understand how project components that often span several years fit together.

The Great Lakes Legacy Act was passed in 2002 to accelerate sediment cleanup in Areas of Concern, waterways blighted by decades of industrial discharges and poor municipal sewage practices. Since then, the program has cleaned up nearly 3 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment and restored acres of habitat.

For additional information or to request that your waterbody be added to the website, contact Caitie McCoy.

February 11th, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

We talk a lot about the environmental benefits of sediment remediation. These are hard to miss—a trip to the river or harbor is often all it takes to confirm that the aquatic habitat is on the mend. The role of cleanup projects on local economies can be harder to pin down, but the impacts are just as striking. Brandon Steppan, IISG’s new communications intern, has the story.

I’ve lived in the city all my life. With the exception of a few parks and forest preserves, I never really saw environmental health as being all that connected to the welfare of my community. The only rivers that ever made the news were the Chicago River on St. Patrick’s Day and the Des Plaines River whenever it flooded—especially if that meant Gene and Jude’s, an iconic hot dog stand in River Grove and arguably the best place to get a Chicago-style hot dog, would have to shut down for repairs.

What I’ve learned about other Great Lakes communities in the short time I’ve been with IISG has already made me reevaluate just how valuable a healthy river can be—not just in terms of environmental integrity, but in dollars and cents. Results of economic studies of Great Lakes Areas of Concern (AOCs) have listed the values of what a clean waterbody would be for those communities, with numbers ranging from $6 million for one small neighborhood to $19 billion for all 31 original AOCs in the U.S. To get these numbers, economists and social scientists looked at money brought in from tourism, real estate values, and residents’ willingness to pay for a cleaner waterway.

One of the more remarkable returns came from a 2004 examination of the Waukegan Harbor AOC in Illinois. An analysis of housing data and resident perceptions determined that proximity to the PCB-ridden harbor substantially drove down property values. When surveyed, Waukegan homeowners revealed they would be willing to pay more for their property if it meant full cleanup of the harbor—a collective value of $436 million, much more than the projected cost for remediation.

My initial reaction to these reports was a mixture of confusion and surprise. But as I took into account the number of people in each area and how they rely on their local rivers not just for livelihood but for quality of life, the numbers no longer seemed all that surprising. The hazards of a toxic river bed aren’t always obvious, and unfortunately, neither are the benefits of remediation. Having these numbers available helps create a conversation where those benefits are no longer vaguely environmental, but economically tangible.

***Photo from the Waukegan Port District.

November 3rd, 2014 by iisg_superadmin

After decades of remediation work, two Michigan sites are no longer considered Areas of Concern (AOCs). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency officially removed Deer Lake in the Lake Superior basin and White Lake in the Lake Michigan Basin from the list of toxic hot spots last week.

These are the third and fourth U.S. sites to be delisted since a 1987 cleanup agreement with Canada identified areas hit hardest by legacy pollutants like PCBs and mercury. The Oswego River in New York became the first in 2006, and Pennsylvania’s Presque Isle Bay was delisted last year.

From the Detroit Free Press

The Deer Lake AOC, along the southern shore of Lake Superior on the Upper Peninsula, was listed because of mercury contamination that leached into water flowing through an abandoned iron mine, as well as other pollutants. Mercury contamination in fish—and reproductive problems—also were documented in animals and birds, including bald eagles.

The remediation efforts included a Great Lakes Restoration Initiative grant for $8 million that helped pay for a project diverting water from Partridge Creek. It previously fed the stream flowing through old mine workings under Ishpeming, which then ran into another creek and into Deer Lake.

The White Lake AOC was on Lake Michigan in Muskegon County and had been contaminated by pollution—especially organic solvents—from tannery operations, chemical manufacturing and other sources, degrading fish and wildlife habitats.

A $2.5-million grant was used to remove contaminated sediment and restore shoreline, with more than 100,000 cubic yards being removed. Read more

More than two dozen AOCs remain throughout the Great Lakes states. But as many as 10 are targeted for completion in the next five years thanks in part to funding from the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, which will enter its second phase next year.

Two of the sites slated for delisting are the Buffalo and Grand Calumet rivers, where IISG’s Caitie McCoy has partnered with federal, state, and local groups under the Great Lakes Legacy Act to connect nearby communities with the remediation and restoration. A big part of this work has focused on integrating environmental cleanup projects into the classroom with place-based curriculum and stewardship projects.

***Deer Lake in Ishpeming. Credit: Stephanie Swart, Michigan Department of Environmental Quality.

October 30th, 2014 by iisg_superadmin

For anyone familiar with the Grand Calumet River, the changes over the last few years are impossible to miss. The historically industrialized river, long ago abandoned by both people and wildlife, is now home to birds, fish, and other aquatic life in many areas. The revitalization is due to a series of remediation and restoration projects that will remove more than 2 million cubic yards—roughly 130,000 dump trucks—of contaminated sediment and add native plants to banks and marshes by 2015.

The east branch of the river is one of these revitalized areas, and it is there that representatives from government agencies and non-profit organizations, including IISG’s Caitie McCoy, met earlier this month for a tour of the remediation projects.

The tour, coordinated by Save the Dunes, was aimed at highlighting the work and thanking representatives from the offices of U.S. Rep. Pete Visclosky, D-Merrillville, and U.S. Sen. Joe Donnelly, D-Ind., for their support in the efforts and encouraging support for future funding.

“They’ve been our champions to maintain (Great Lakes Restoration Initiative) funding for the last four or five years,” Nicole Barker, executive director of Save the Dunes, said. “We are indebted to them.”

The group visited some of the river’s biggest success stories, including Roxana Marsh, which has been free of high levels of PCBs and heavy metals for over two years. They also heard from officials about local changes that are helping to secure the long-term health of the river. In Hammond, IN, for example, raw sewage that was previously discharged into the newly-remediated river is now being redirected to the city’s wastewater treatment plant.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the tour came during the stop at Seidner Marsh. Remediation for this part of the river wrapped up earlier this year and attention has been turned to dredging wetlands and rebuilding habitats. The group was able to see these efforts first-hand as workers delivered barge after barge of fresh sand to be spread along the riverbed.

“It is important that these restoration projects do more than just remove contaminated sediment,” said Caitie. “We also want to help jumpstart wildlife populations, and that includes the invertebrates and microorganisms that live at the bottom of the river. The clean sand gives them a home, a place to burrow in.”

Cleanup and restoration on the Grand Calumet will continue for many years—six of the nine project areas are still in progress. But residents and visitors can expect to see a clean river bottom with a thriving plant community as early as 2024.

October 13th, 2014 by iisg_superadmin

The Trenton Channel, part of the 32-mile Detroit River, could see a cleanup in 2016 through the Great Lakes Legacy Act, which combines federal funding with local support. Before that can happen though, voluntary partners must agree to help fund this final cleanup stage. The Detroit River is one of 29 remaining Areas of Concern in the U.S., a result of decades of poor environmental practices. The fast-moving Trenton Channel is one of the top sources of pollution in the river system due to its history of industrial and municipal practices.

Scientists and engineers are currently designing a cleanup plan to address approximately 240,000 cubic yards of sediment in the upper portion of the Trenton Channel. A majority of the community surrounding this remediation project is looking with optimism and enthusiasm to the clean-up efforts. Yet these feelings are by no means unanimous.

Caitie McCoy, IISG social scientist, and her two summer interns—Mark Krupa and Erika Lower—conducted a needs assessment with local stakeholders of Trenton Channel, including environmentalists, recreation enthusiasts, property owners, and city officials. They found that the channel is viewed as important to the region, but that the clean-up plan is viewed with some skepticism.

Caitie explains:

I assumed that everyone would be overjoyed that a sediment remediation project was happening in their community. Yet there were quite a few concerns about the safety and effectiveness of the project. About a third of the stakeholders we interviewed said that cleaning up pollution would provide no significant community benefits.

This needs assessment has given our outreach team a better sense of what is important to our stakeholders. We have a better sense of what information they want about this project.

Increasingly, social science provides the go-to method for Sea Grant programs to develop informed outreach efforts. In the 2014-2015 research cycle, 29 programs funded 59 social science research projects. Additionally, state Sea Grant programs are hiring social scientists.

More from Caitie:

Large-scale needs assessments are a wise investment for big outreach projects. Needs assessments give us detailed information about our audience concerning a topic of interest–in this case, it was sediment remediation. This information would otherwise be difficult to obtain. Even working with an outreach team composed of local leaders, we make a lot of assumptions about our stakeholders. Needs assessments help us cut through those assumptions so that we can understand what our stakeholders are really interested in or concerned about. This helps us design better messaging and better outreach events for our stakeholders.

To learn more about what the researchers learned from Trenton Channel stakeholders, you can download A Needs Assessment for Outreach in the Detroit River Area of Concern’s Trenton Channel.