July 25th, 2018 by Carolyn Foley

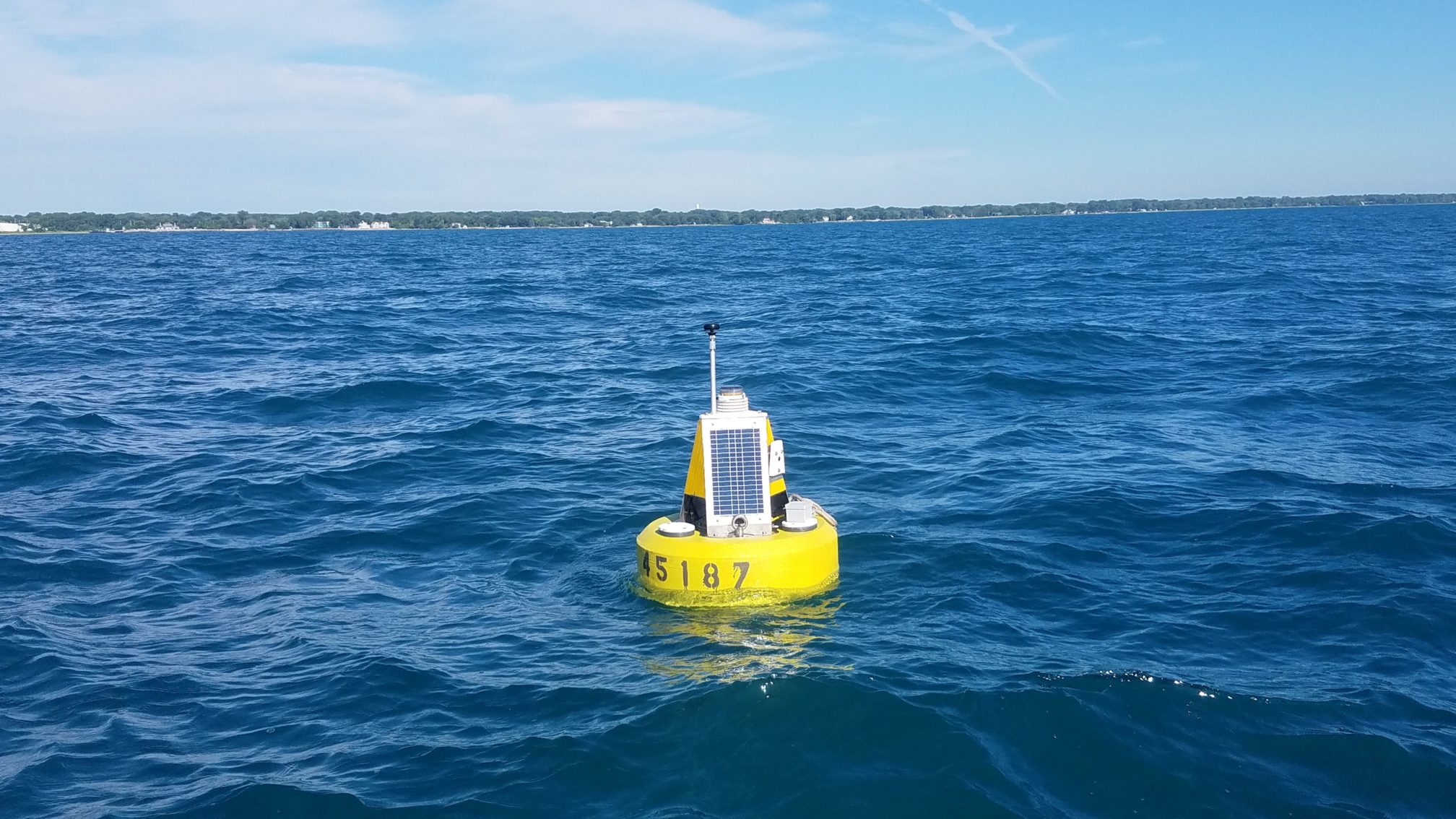

Lake Michigan now has two new buoys that monitor lake conditions in real-time. Placed about a mile offshore in Illinois waters—close to Waukegan and Winthrop Harbor—each buoy will measure air and water temperatures, wave and wind conditions, and water currents every 20 minutes while deployed. The buoys are also equipped with webcams that transmit an image and video once per hour during daylight hours. Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant will host the most recent data and images on their program website, while data will be managed by Great Lakes Observing System (GLOS).

Ethan Theuerkauf and colleagues from the Illinois State Geological Survey (Prairie Research Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) and the Illinois Department of Natural Resources Coastal Management Program have been working to deploy these buoys for several years. “We plan to use the buoy data to study the drivers of erosion along the Illinois shoreline,” said Theuerkauf, a scientist with the Illinois State Geological Survey and an adjunct professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “It is a bonus that so many boaters and swimmers can also use the information.”

“It’s great to have two more systems that will help scientists and weather forecasters understand what’s happening in the Illinois and Indiana waters of Lake Michigan,” said Jay Beugly, an aquatic ecology specialist with Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, who helped place the buoys in the water on July 19 and is the main support for the Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant real-time buoy program.

Photo credit: Ed Verhamme, LimnoTech, Inc.

Ed Verhamme, a project engineer with LimnoTech, Inc., designed and custom-built these buoys for application along the Illinois shoreline. “These buoys are closer to shore than other buoys in Lake Michigan, which helps scientists better understand how waves and currents affect the shoreline, but also required us to use a different type of buoy”, said Verhamme who also joined Beugly and Theuerkauf during the buoy deployment.

As of July 23, 2018, data from the two new buoys can be found via the GLOS data portal and the National Data Buoy Center by searching buoy numbers 45186 (Waukegan) and 45187 (Winthrop Harbor). These buoys were supported by a NOAA Coastal Zone Management Projects of Special Merit Grant.

Contact: Ethan Theuerkauf ejtheu@illinois.edu, Ed Verhamme everhamme@limno.com, Jay Beugly jbeugly@purdue.edu

August 28th, 2016 by IISG

The first thing IISG Assistant Research Coordinator Carolyn Foley does each morning is feed her kids. Then, while toast is toasting or oatmeal is warming up, she checks the IISG real-time buoys.

“Jayson Beugly, Angela Archer, and I all monitor the buoys to make sure they’re transmitting OK,” Foley said. “But I also look for cool things that are being captured.”

Foley shares these “cool things” via the @TwoYellowBuoys Twitter feed that was conceived during a 2015 IISG staff meeting.

“Jay and I were sitting next to each other during a talk about engaging with social media,” Foley recalled. “He turned to me and said, ‘We should make a Twitter account for the buoys.’ And we both began to laugh.”

Carolyn admits she didn’t know much about Twitter before starting @TwoYellowBuoys, but it seemed like a great platform for communicating the graphs and images constantly generated by the buoys.

“I think visually, and my favorite part of writing scientific manuscripts is putting together graphs in order to tell a story. I hope that seeing how the data illustrate trends and phenomena helps people better understand how scientists use the data to answer complex questions,” said Foley.

“And it doesn’t hurt that looking at the webcam pictures reminds me why I do what I do, especially when I haven’t been able to get near the water lately.”

IISG owns and operates two nearshore buoys in Lake Michigan, one in Michigan City, Indiana and another in Willmette, Illinois. The weather buoys serve a variety of audiences, from the National Weather Service to recreational water users. Data from the buoys, including information on water temperature, wind speed, wave height, solar radiation, and more, is transmitted every 10 minutes.

Foley is especially partial to posting thermocline data on Twitter because she knows anglers make decisions based on water temperature.

The buoy dashboards provide this data in both numerical and graphical form, and users can even access historic data. In addition, webcam images are captured every hour during daylight hours and shared online.

Using @TwoYellowBuoys, Foley has featured local and Lake Michigan-wide comparisons of water temperatures, air temperatures, wave heights, wind speeds, and more. She also pulls together images from the webcams atop the buoys to share with followers.

“It’s not up to us to predict what’s going to happen—the National Weather Service and others use the data for that purpose,” said Foley.

“But to be able to visualize what has happened and link it to real things that people have experienced, like storms or temperature shifts, is really fun and hopefully neat for people to see and understand.”

Carolyn Foley and Abigail Bobrow also contributed to the story. Joel Davenport created the illustrations.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

June 9th, 2016 by IISG

IISG Associate Director of Research Tomas Höök has been elected president of the International Association for Great Lakes Research (IAGLR) for the 2016-2017 term. IAGLR, which got its start in the 1950s, is an organization made up of scientists conducting research of large lakes throughout the world.

Höök, currently the vice president, has been member of the organization since his days in graduate school at the University of Michigan.

“We try to keep IAGLR functioning smoothly and facilitating exchange of research information regarding large lakes of the world,” said Höök. That said, we are also exploring opportunities to grow IAGLR. Specifically, we are seeking to hold meetings in addition to the annual conference on Great Lakes research. Ultimately, we hope to better connect Great Lakes researchers with environmental managers, communicators, and educators.”

This year’s IAG LR conference was held in Guelph, Ontario from June 6-10 and several IISG researchers presented and chaired sessions.

LR conference was held in Guelph, Ontario from June 6-10 and several IISG researchers presented and chaired sessions.

Jay Beugly, aquaculture ecology specialist, presented on the usefulness real-time buoy data provides to a variety of stakeholders, ranging from recreational boaters to weather service professionals in the southern basin of Lake Michigan. Fellow IISG collaborators Carolyn Foley, Angela Archer, and Tomas Höök, along with Cary Troy of Purdue University, and Ed Verhamme, of LimnoTech were also part of the project.

A presentation by Community Outreach Specialist Kristin TePas shared best management practices for setting up and conducting science-based videocalls with K-12 classrooms. She also co-chaired a session on Great Lakes education and outreach.

Carolyn Foley, assistant research coordinator, shared her work on the contribution and effects of different terrestrial nutrient sources on the diets of small-bodied fishes in nearshore Lake Michigan.

Paris Collingsworth, Great Lakes ecosystem specialist, presented findings from research derived from two programs that monitor phosphorus and chlorophyll in Lake Erie. The goal was to paint a more complete picture of lower food web level dynamics. Collingsworth also co-chaired a session dedicated to ecological connections in Lake Michigan.

In addition to contributing to eight presented projects, Tomas Höök a co-chaired a session on the global stressors on large-lake ecosystems.

November 3rd, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

Every year as winter approaches, the Michigan City and Wilmette buoys are taken out of Lake Michigan. So we were wondering, what happens to them? Where do they go? The best people to tell us about the off-season lives of the buoys are the individuals who work the closest with them — IISG Assistant Research Coordinator Carolyn Foley and Aquatic Ecology Specialist Jay Beugly. Here’s what they had to say.

Why do we need to take the buoy out? Why can’t it stay in all year? The main reason to take the buoy out is that the lake ices over in the winter. Weather conditions when there is not ice can also get very, very rough — rougher than what the buoy is meant to withstand (though we’re always trying to make things stronger and more rugged). The delicate instruments that take measurements also need to be cleaned and maintained to be sure we can keep transmitting the best data possible.

Is it hard to get it out? It must weigh a lot! How many people does it take? It is much easier to retrieve the buoy at the end of the year than to put it out in the springtime. You usually need one person to captain the boat and 4-5 people to help pull up the ballast weights and stop the buoy from bouncing against the boat.

Where does the buoy go once it’s out? A warehouse? A garage? The buoys are usually stored at the Purdue University West Lafayette campus, in the Civil Engineering building. Sometimes they are stored at LimnoTech’s headquarters, in Ann Arbor, MI. The buoys tend to move around during the winter, especially if they need upgrades. So keep your eye out for buoys on trailers when you’re travelling down I-65 or I-94.

Aquatic species attach easily and quickly to things in the water. Has that ever happened to any of the buoys? What did you do? Every year! Quagga mussel veligers floating around Lake Michigan are always looking for hard structures to attach to, and even if we only put the buoy out for one month, we find young quaggas that have attached themselves. Though some of the surfaces on the buoy are smooth enough to stop the quaggas from attaching, they always manage to find their way into nooks and crannies. We carefully inspect the buoy before leaving the lakeside and remove anything we see, either manually or with help from a hose.

Does the buoy get a tune-up? Like a thorough wash-down? A paintjob? The main hull gets cleaned off and all of the sensors are removed and cleaned. Depending on the sensor, this may mean an acid wash or just a good wipe down. One year we had to replace a solar panel that had completely fallen off, so we’re always double-checking that everything is where it’s meant to be.

What happens to the buoy website? Is all the archival data still available? The IISG buoy data websites go offline while the buoys are not in the water, but the main IISG buoy pages are still active. Historic data can always be found at the NDBC page (buoys 45170 and 45174, respectively), and at greatlakesbuoys.org. People who want to use the data should pay attention to notes like “Data have not been quality-checked” – if the data haven’t been quality-checked, they may contain really weird, fluke readings (like the 100-foot wave that the Michigan City wave height sensor recorded in 2014). We try to quality check the whole year of data within a few months of retrieving the buoy. People are also always welcome to email us to ask questions about the data.

August 6th, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

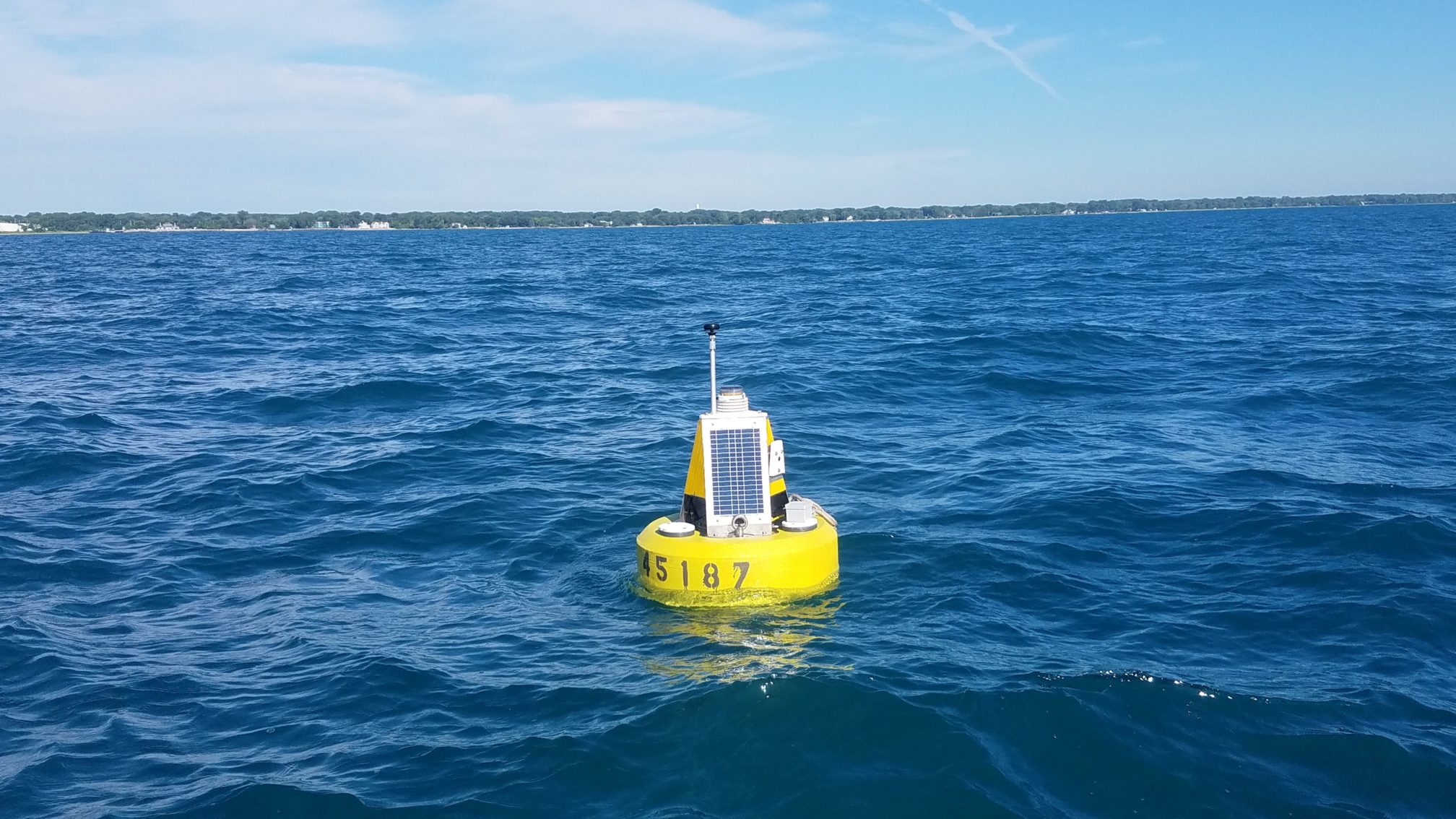

Boaters and beachgoers visiting the Chicago area this summer will have access to even more real-time data on lake conditions with a second nearshore environmental-sensing buoy that was launched in Lake Michigan on Tuesday, August 4, 2015.

The new buoy, located roughly four miles off the coast of Wilmette, Ill., relays information on wind speed, air and water temperature, wave height and direction, and other environmental characteristics from May to October each year.

Tom Palmisano, an owner of Henry’s Sports and Bait shop in Chicago, volunteered his boat and time to take out the anchor portion of the buoy.

“The buoy will be useful for anybody who does anything on the water,” said Palmisano, a longtime commercial and recreational diver.

The Sheridan Shore Yacht Club in Wilmette donated use of their crane to lift the hulking sections — totaling over 600 pounds — into the water.

The TIDAS 900 Wilmette buoy is a joint project between Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) and LimnoTech to help advance understanding of nearshore waters, alert the public to hazardous conditions in real time, and improve weather forecasts. Staff from Purdue University Civil Engineering also assisted on the project. This one is also equipped with a webcam enabling people to actually see the conditions on the lake.

“This is a tremendous leap forward,” said Ed Fenelon, a National Weather Service (NWS) meteorologist with the Chicago office. “Before this buoy, there was a data void in almost all of the nearshore area.”

Data from the first buoy launched in 2012 off the coast of Michigan City, Ind., has already led to adjustments in wave forecast models and boosted understanding of fisheries and nearshore dynamics.

Data from the Wilmette buoy will also be used to improve predictions of hazardous weather conditions and issue swim and small water craft advisories.

“To accurately forecast the future, you have to have a detailed measurement of current conditions,” Fenelon added. “This buoy will give us just that.”

Current lake conditions will be updated every 10 minutes and be available at the IISG Wilmette Buoy page. The mobile-friendly sites highlight conditions of particular interest to recreational users, such as wave height, wind speed, and surface water temperature.

Along with graphs showing trends over recent time periods, this information will tell boaters and kayakers when it’s safe to be on the water and help anglers target specific species.

“We have talked with many different groups in the area, from anglers and boaters to scientists, and the response to the buoy has been overwhelmingly positive,” said Jay Beugly, IISG aquatic ecology specialist. “People are excited that this information is so easily accessible.”

The Wilmette buoy was funded through the Great Lakes Observing System (www.glos.us), which is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) greater Integrated Oceanic Observing System network.

Information collected from the buoys is also fed into the National Data Buoy Center (http://www.ndbc.noaa.gov/) operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the more localized http://greatlakesbuoys.org/. Forecasters, researchers, and others can download raw historical data for Michigan City buoy ID 45170 or Wilmette buoy ID 45174 from any of these websites.