August 28th, 2023 by Carolyn Foley

Meet Our Grad Student Scholars is a series from Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) celebrating the graduate students doing research funded by the IISG scholars program. To learn more about our faculty and graduate student funding opportunities, visit our Fellowships & Scholarships page. Les Warren is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources at Purdue University. He is currently in his fourth year, researching the early life history of larval fish in the Laurentian Great Lakes. For the work being funded by the Great Lakes Fisheries Trust and Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, he is particularly interested in how various natal habitats help contribute recruits to the Lake Michigan alewife population.

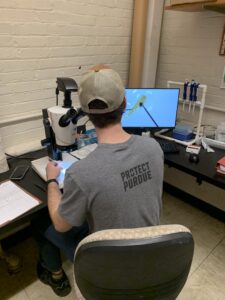

A researcher examines larval fish samples under a microscope. (Photo provide by Les Warren)

In the early 1940s, a small fish from the Atlantic Ocean, alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus), invaded the freshwater habitats of the Great Lakes. Lake Michigan was not excluded from this invasion, and alewife quickly spread throughout the lake. High densities of alewife began to degrade critical habitats and alewife carcasses clogged water intake pipes after winter die-offs. In the 1960s, successful stocking of Pacific salmonids like Coho and Chinook Salmon provided a much-needed predator for alewife. This led to both a decline in the alewife population and the establishment of a major recreational salmonid fishery.

Salmonids have since then become one of the largest recreational fisheries in Lake Michigan, and tourism and charter fishing targeting Pacific salmonids provide a strong economic impact for the surrounding states. Since the early 2000s, however, alewife populations have been on the decline and are currently at an all-time low. This decline in abundance could be attributed to several factors, including habitat degradation and the over-stocking of salmonid species. Although some species of salmonids are flexible in their diets, Coho and Chinook Salmon rely heavily on alewife for up to 90% of their diet.

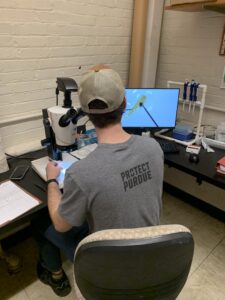

A larval alewife collected from Lake Michigan. (Photo provide by Les Warren)

Les Warren, a PhD student in Hook Lab at Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, is studying the early life history of alewife and how different habitats may influence the survival and growth of alewife in Lake Michigan. Alewife spawn in multiple habitats in Lake Michigan, including drowned river mouth lakes (DRMLs), tributaries, and nearshore environments. Due to its large volume compared to other habitats, the nearshore region of Lake Michigan has been considered the primary source of alewife recruits by previous studies using modeling approaches. However, the main basin of Lake Michigan has undergone ecological changes such as lower productivity offshore, greater water clarity and lower food web changes. These changes are attributed to actions such as lower nutrient loading from tributaries into the lake and the invasion of dreissenid mussels, which aggressively filter the water column. In the past, habitats like DRMLs provided warm, highly turbid environments with relatively high abundance of prey for young alewife to eat. Previous studies have observed young alewife in these environments experience relatively early hatch dates, high growth rates, and higher probability of survival than that of young alewife reared in the main basin of Lake Michigan.

A net to capture zooplankton is towed vertically through the water. (Photo provide by Les Warren)

Over the summers of 2021 and 2022, Les sampled nearshore habitats of Lake Michigan and supplemental habitats such as DRMLs and tributaries. Sampling locations included Muskegon Lake, White Lake, Trail Creek, and the Saint Joseph River on the eastern shoreline of Lake Michigan. At each location, larval alewife were collected using a paired bongo net and surface neuston net. A paired bongo net contains two nets of different mesh sizes to facilitate the capture of various sized larvae throughout the water column. Neuston nets target larval fish at the surface of the water column. Along with the larval fish tows, zooplankton, sonde profiles, ultraviolet radiation profiles, and secchi depths were collected to further compare these habitats spatially and temporally. With the collection of zooplankton at each site, Les was able to quantify the abundance of prey available for larval fish. Secchi depth is a way to compare water clarity between habitats and connects directly with exposure to ultraviolet radiation. One exciting aspect of this study was the ability to work with collaborators at Miami University to assess the amount of potential UV exposure for larval fish in each of these habitats.

A researcher examines bongo nets after they have been towed in Lake Michigan. (Photo provide by Les Warren)

Sampling on a weekly basis during two consecutive summers was a logistical challenge. Sampling for Les’s project required scheduling around weather, scientists’ time, and plans to share equipment with the other graduate students and researchers in his lab. However, Les claims that the real work began after bringing all the samples back to the lab. Each sample needed to be picked for larval fish since the nets are rinsed down and the resulting samples are concentrated on the boat. Undergraduate technicians sorted through other matter, including algae and zooplankton, to extract the larval fish from the samples. Once picked, the larvae species were identified before extracting otoliths — ear stones that exhibit alternating light and dark rings, similar to those of a tree — to determine the ages of the larval alewife.

Although the results of the study are in the early stages, the DRML and river mouth habitats were warmer, more turbid, and had higher zooplankton densities than Lake Michigan. Larval alewife emerged on average two weeks earlier in these habitats and, overall, relative larval densities and daily growth rates of larval alewife were higher in the DRMLs and river mouths compared to the nearshore waters of Lake Michigan during both sampling seasons. Results from this study will be compared to a previous study performed 20 years earlier to provide evidence that DRMLs and river mouths are becoming increasingly important habitats to sustaining a healthy alewife population in Lake Michigan.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a partnership between NOAA, University of Illinois Extension, and Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources, bringing science together with communities for solutions that work. Sea Grant is a network of 34 science, education and outreach programs located in every coastal and Great Lakes state, Lake Champlain, Puerto Rico and Guam.

Contact: Carolyn Foley

December 19th, 2019 by Irene Miles

As 2019 draws to a close, I’m pleased to report that here at Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, we’ve had a very good year, and that remained the case through the latter months.

In October, IISG underwent its program site review, which takes place every four years. Through this process, we presented our work from our last omnibus as well as our current activities to the external site review team. The review provides a great opportunity to reflect on our accomplishments and to look forward to new efforts.

The review team was very positive in its response, which, in large part, is due to not only the hard work of the IISG team, but also the great amount of support from our diverse partners, many of whom directly participated in the review.

This fall, we expanded our communication tools and products to share information about the Great Lakes with wider audiences. Inspired by a rich collection of photographs taken by Peter Essick, who works with National Geographic, IISG led the development of a photo essay called Great Lakes Resurgence about Areas of Concern in the region. The Great Lakes Sea Grant Network collaborated to tell the stories of these degraded waterways, to describe the progress of cleanup efforts and report local impacts of coastal restoration.

IISG now has a monthly podcast series, Teach Me about the Great Lakes, which debuted in December. Hosted by Stuart Carlton, the program’s assistant director, the podcast helps Stuart—and listeners—learn about the biology, ecology and natural history of the Great Lakes. Stuart is a social scientist who grew up in the south, so he is fairly new to Great Lakes issues. The first installment dove into concerns about microplastics, which have been found in the Great Lakes and many waterways all over the world. The next episode, available in early January, will focus on the geological history of the Great Lakes.

Autumn also brought awards season for the Sea Grant program, both regionally and nationally. We are proud of Pollution Prevention Specialist Sarah Zack, who was honored with the Great Lakes Sea Grant Network Early Career Award at the regional meeting in Sault St. Marie, Michigan. Irene Miles, strategic communication coordinator, won the Communications Service Award at the Sea Grant Extension Assembly, Communicator and Research Coordinator Conference in Savannah, Georgia. Also at the Savannah meeting, Brian Miller, IISG’s former director, was selected for the William Q. Wick Visionary Career Leadership Award, one of Sea Grant’s most prestigious honors.

As we all look forward to 2020, we wish you the best in the new year. For IISG, 2020 will bring an even greater focus to Lake Michigan. Scientists from around the Great Lakes basin will converge on the lake to conduct intensive research through the Cooperative Science and Monitoring Initiative (CSMI). IISG has just released an ESRI story map, Lake Michigan Health: A Deeper Dive, to share the results from the 2015 CSMI field year on Lake Michigan.

The Shipboard Science Workshop will also take place on Lake Michigan in the coming year. During this week-long workshop on the EPA research vessel the Lake Guardian, organized through the Center for Great Lakes Literacy, teachers from the region work side by side with scientists to study one of the Great Lakes. This coming year they set sail on Lake Michigan. We look forward to new science and stories that will emerge from both of these exciting initiatives.

Tomas Höök

Director, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

November 1st, 2018 by IISG

The Lake Michigan Sea Grant programs, including Wisconsin Sea Grant, Michigan Sea Grant and Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, seek integrated proposals to better understand coastal hydrodynamics and nearshore sediment transport processes on Lake Michigan, to help effectively communicate this information to promote sustainable shore protection, and to increase the integrity of beaches and stabilize bluffs. The result would be more resilient coastal communities and economies.

Research is to be conducted in the 2020–22 biennium. Up to $100,000 per year for two years will be available for funding each of the Michigan, Wisconsin, and Illinois-Indiana portions of a joint research project (i.e., up to $300,000 per year total). Michigan and Illinois- or Indiana-based partners must demonstrate a 50 percent match (1 non-federal dollar for every 2 dollars requested). Match is not required for Wisconsin partners.

By partnering, the three Lake Michigan Sea Grant programs can support broader-scale projects to tackle challenges at a regional scale. In addition, generating collaborations across state lines can enrich the expertise of our in-state research teams.

Pre-proposals must demonstrate plans for collaboration between researchers from two (2) or three (3) of the state programs. The amount of funding available to the research team depends on the number and nature of collaborating partners; e.g., a researcher from Michigan and a researcher from Wisconsin could submit a proposal together for up to $400,000; researchers from Michigan, Wisconsin, and Illinois could submit a proposal together for up to $600,000.

More Information

Deadline

- Pre-proposals are due by 3pm CST (4pm EST) Friday, January 11, 2019.

Questions

For more information, Illinois and Indiana partners can contact Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant Research Coordinator Carolyn Foley (cfoley@purdue.edu).

If you have interest in this topic and/or skills that would be relevant to a research team but you are not sure who to connect with in other states, contact Carolyn Foley (cfoley@purdue.edu), who can provide a Google doc link that is a resource for researchers who may be interested in partnering. Listing your information in this Google doc is not a requirement for submission to this RFP. It simply serves to help researchers find relevant partners.

August 22nd, 2018 by iisg_superadmin

The economic impact of the Illinois and Indiana Lake Michigan recreational fishery on the local economy was more than $44 million in 2015, according to Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) research. Recreational fishing supported 407 jobs in the two states.

IISG funded two studies to estimate the economic value of the Lake Michigan fishery in Illinois and Indiana. At the Illinois Natural History Survey (INHS), Sergiusz Czesny, Craig A. Miller, and graduate student Elizabeth Golebie looked at how much anglers actually spend and estimated the impact of those dollars.

They questioned anglers about their typical fishing trip expenses and found that shore-based anglers spent an average of $56 and boating anglers spent $255. Annual creel surveys, which are done in person along the shoreline, provided a point of contact so that the researchers could target their questionnaires to anglers who fish in Lake Michigan. In Illinois, INHS is responsible for the creel surveys along the shoreline in Cook and Lake counties. In the Indiana counties of Lake, Porter and LaPorte, the creel surveys are done by the state’s Department of Natural Resources.

The researchers estimated the total economic impact of Lake Michigan non-charter anglers in Illinois waters at $22.4 million, providing 231 jobs. Indiana non-charter anglers contributed $12.7 million to the local economy, supporting 176 jobs in the three counties. Illinois charter fishing anglers were also included in this study and comprised the remaining economic impact that altogether totaled more than $44 million.

“There’s a wide range of economic activity going on with fishing,” said Miller. “These numbers provides more evidence that we need to maintain these fisheries. Several sectors of the economy are dependent on a healthy fishery with healthy fish populations and angler access.”

In both states, the overwhelming majority of fishing—75 percent—was for salmon species, which include coho and chinook salmon, as well as brown, lake and rainbow trout. Only 6 percent was dedicated to yellow perch, and the remainder for other species, such as bass.

Mitchell Zischke and graduate student Xiaovang He at Purdue University, and Benjamin Gramig at the University of Illinois tell more of the story in their economic evaluation research. Using a non-market approach to quantifying the value of the Lake Michigan fishery in the two states to the anglers themselves, they estimated anglers’ willingness to pay for a day-trip spent fishing. They added questions to the 2015 Illinois and Indiana creel surveys to do a travel cost study, estimating the value of fishing based on how far anglers traveled and how much time it took to get to fishing sites.

“In addition to direct expenditures, anglers allocate time and effort to fishing instead of work or other activities, and this is the basis for these estimated values,” said Gramig.

Anglers interviewed during the 2015 creel surveys along Lake Michigan were willing to pay an average of $30 to take a day trip fishing and their average travel distance was 28 miles. Illinois anglers have a slightly higher willingness to pay than those from Indiana and boaters have a higher average, at $40, than shore-based anglers, who are willing to pay $26.

The total estimated non-market economic value of recreational fishing was $3.6–4.0 million, which represents additional value over and above expenditures on food, fishing supplies and other associated items included in Miller and Czesny’s estimates.

“Support for the economy through recreational fisheries is a complex web,” said Zischke. “Having some understanding of these numbers is important. For example, if there’s a potential to open up a fishing site, it’s critical to know that it may add millions of dollars to the economy.”

Zischke and Gramig also looked at 30 years of creel survey data to get a historical perspective on the Lake Michigan fishery and connect trends with environmental or management changes.

The data revealed that while the two states share Lake Michigan waters, they have noteworthy differences in fishing practices. “We noticed a large decline in the fishing effort in Illinois,” said Zischke. Fishing effort back in the mid-1980s added up to over 2 million angler hours per year—since the early 2000s it has stabilized at 500,000 annual angler hours.

Zischke attributes the reduction in Illinois fishing hours to the drop in yellow perch numbers. “The decline in fishing effort follows a similar timeline to declines in catch rates of yellow perch,” he said.

“In Indiana, however, we did not find a similar decline in fishing hours,” said Zischke. “Fishing hours have been stable at 300,000–400,000 over the last 30 years. Typically, the catch rates of yellow perch in Indiana have been historically lower than in Illinois and they have actually been quite stable through time.”

The historical creel survey data also revealed that most Illinois anglers have engaged in shore-based fishing, whereas Indiana anglers have been predominantly on boats. This may be due to the fact that Illinois has a higher population along the lakefront and more access to fishing along its shores.

The research team has made the creel surveys’ 50,000 records collected from 1986 to 2013 available for other researchers, resource managers and anglers to easily access on the Angler Archive website. Plans are in the works to update the website with more recent data.

July 5th, 2017 by Carolyn Foley

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) is proud to support two real-time monitoring buoys in southern Lake Michigan, one located just north of Michigan City, Indiana and the other near Wilmette Harbor, Illinois. Recently, users have started pitching in with donations to help keep the buoys afloat.

The buoy program started when a Purdue researcher pointed out that there were no real-time data being collected in Lake Michigan’s Indiana waters. A few years later, concerned citizens and sailors pointed to a similar need for the Illinois shoreline. Now, the two IISG buoys are filling information gaps for anglers, sailors, swimmers, and weather professionals who are interested in this part of the lake.

Over the years, buoy users have made phone calls, emails, and interactions through Twitter and Facebook to share that the buoys are valued and needed. We at Sea Grant have enjoyed hearing how our fans use buoy information. All told, lake enthusiasts are checking our real-time buoy data nearly 30,000 times per year!

Putting a buoy in the water, year after year, requires many things to happen. Weather conditions, equipment, people, and technical services have to come together perfectly to keep the buoys operational. This program would be impossible without sufficient funding.

Sea Grant’s buoy managers, Carolyn Foley and Jay Beugly, try to support the buoys with grants, but those funds can be hard to come by. When the unexpected happens, like a power-generating solar panel comes loose, or it takes three trips to remove a hook found tangled in wires at a depth of 30 feet, we burn through our funds pretty quickly.

IISG is constantly on the lookout for partnerships to help keep the buoys afloat, but you can also make a donation. The funds raised will go directly toward the buoy program, supporting data charges, travel costs, repairs, and upgrades. Already, folks are stepping up and donating to keep the buoys operational.

We love providing the buoy data as a service to everyone and helping families stay safe during these summer days. Please join your fellow buoy fans and consider donating today!

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

January 10th, 2017 by IISG

Researchers at Purdue University are suggesting that fishing by Lake Michigan charter boat anglers has changed in recent years—and the scientists didn’t even have to visit the lake to notice these differences.

In fact, Nicholas Simpson who is the primary author on the study has never even fished Lake Michigan.

Working with Tomas Höök, fisheries ecologist and IISG associate director for research, Simpson, then an undergraduate, compiled 21 years of charter fishing data obtained from the Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin Departments of Natural Resources (DNR).

The data, derived from more than 500,000 trips, were readily available from the records charter anglers are required to report to their state DNR after each trip: number of fish harvested—not just caught, location fished, and hours spent fishing.

Simpson, Höök, and their co-authors evaluated patterns for five salmonid species—brown trout, Chinook salmon, coho salmon, lake trout, rainbow trout—harvested from May to September during 1992–2012.

“Because we’re looking at charter fisherman data, there are some biases,” Höök acknowledged. “They’re not randomly going out to catch fish. They go where they believe they’re more likely to catch fish.”

But there is an advantage to examining these data. Researchers often attempt to catch fish in a systematic, unbiased way, and may be limited by factors, such as funding timelines or resources. As a result, “the number of times the lake is fished or the overall number of fish caught wouldn’t be that much,” Höök pointed out. “Here we’re taking advantage of a huge number of people fishing over a long time period.”

The data set covers a time when the lake itself has changed dramatically. Lake temperature and other physical and biological factors are different today than they were in 1992. Over the course of the data set, the distribution and number of prey fish, such as alewives, available for salmon varied greatly.

In addition, while it may be hard to remember a time when zebra and quagga mussels—invasive filter feeders—didn’t line almost every inch of Lake Michigan, zebra mussels were just becoming an issue in the first year of data. Numerous studies have suggested that the mussels have changed the structure of the Lake Michigan food web over time.

The researchers assumed that salmonid species would not be immune to these changes, and some patterns emerged from the charter anglers’ records.

Over time, the amount of time charter anglers spent fishing increased. The anglers also shifted their efforts closer to shore and toward the western and northern parts of Lake Michigan. However, patterns in the harvest of individual salmonid species paint a complicated picture.

Harvest of lake trout and rainbow trout by charter anglers shifted closer to the shore. The same was not true for Chinook and coho, where harvest was consistently farther out in the lake. Brown trout were harvested progressively further west and south, while lake trout were harvested progressively further east. Multiple species were harvested in new locations and at new depths.

In general, the researchers suggest that many of the changes are related to salmonid feeding.

“Previous research has shown the brown trout and rainbow trout and to an extent lake trout are a little more flexible in their diets,” Simpson said. “They were more apt to shift closer to shore and to shallower depths for food. Chinook salmon and coho salmon may not have displayed those trends because they’re more reliant on alewife as prey, which tend to live farther out in the lake.”

“There’s no previous research in the literature that would suggest that coho or Chinook salmon would vary their diet as much as the other three species,” Simpson added.

The researchers stopped short of definitively declaring that fish are changing where they dwell in response to changes in distributions of Lake Michigan nutrients and prey, but they’re confident the results from this paper will be useful.

“The depth and breadth of this data set is what makes it powerful,” said Höök. “While we have to be aware of the biases, fisheries researchers do use catch and harvest data to infer species distributions.”

And while fisheries managers will ultimately need to consider this analysis alongside their own monitoring efforts, Simpson said, “I think it’s useful for fisheries managers especially on Lake Michigan to be able to see that there are shifts occurring.

The study on their findings was recently published in the Journal of Great Lakes Research.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

August 28th, 2016 by IISG

The first thing IISG Assistant Research Coordinator Carolyn Foley does each morning is feed her kids. Then, while toast is toasting or oatmeal is warming up, she checks the IISG real-time buoys.

“Jayson Beugly, Angela Archer, and I all monitor the buoys to make sure they’re transmitting OK,” Foley said. “But I also look for cool things that are being captured.”

Foley shares these “cool things” via the @TwoYellowBuoys Twitter feed that was conceived during a 2015 IISG staff meeting.

“Jay and I were sitting next to each other during a talk about engaging with social media,” Foley recalled. “He turned to me and said, ‘We should make a Twitter account for the buoys.’ And we both began to laugh.”

Carolyn admits she didn’t know much about Twitter before starting @TwoYellowBuoys, but it seemed like a great platform for communicating the graphs and images constantly generated by the buoys.

“I think visually, and my favorite part of writing scientific manuscripts is putting together graphs in order to tell a story. I hope that seeing how the data illustrate trends and phenomena helps people better understand how scientists use the data to answer complex questions,” said Foley.

“And it doesn’t hurt that looking at the webcam pictures reminds me why I do what I do, especially when I haven’t been able to get near the water lately.”

IISG owns and operates two nearshore buoys in Lake Michigan, one in Michigan City, Indiana and another in Willmette, Illinois. The weather buoys serve a variety of audiences, from the National Weather Service to recreational water users. Data from the buoys, including information on water temperature, wind speed, wave height, solar radiation, and more, is transmitted every 10 minutes.

Foley is especially partial to posting thermocline data on Twitter because she knows anglers make decisions based on water temperature.

The buoy dashboards provide this data in both numerical and graphical form, and users can even access historic data. In addition, webcam images are captured every hour during daylight hours and shared online.

Using @TwoYellowBuoys, Foley has featured local and Lake Michigan-wide comparisons of water temperatures, air temperatures, wave heights, wind speeds, and more. She also pulls together images from the webcams atop the buoys to share with followers.

“It’s not up to us to predict what’s going to happen—the National Weather Service and others use the data for that purpose,” said Foley.

“But to be able to visualize what has happened and link it to real things that people have experienced, like storms or temperature shifts, is really fun and hopefully neat for people to see and understand.”

Carolyn Foley and Abigail Bobrow also contributed to the story. Joel Davenport created the illustrations.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

June 2nd, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

With the water sports season in full swing, a coalition of Indiana officials and community groups is hosting a Water Safety Day to raise awareness of safe boating and swimming practices. Hoosiers are invited to the U.S. Coast Guard Station in Michigan City on June 6 from 10 am to 2 pm.

More than 20 people drowned in Lake Michigan last year, and many of those incidents took place at the southern end of the lake. Since 2010, roughly 380 people have drowned in the Great Lakes according to data collected by the Great Lakes Surf and Rescue Project (GLSRP).

Water Safety Day will feature information on everything from choosing proper boating equipment to tools developed by the National Weather Service (NWS) and Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM) that tell beach-goers when and where it’s safe to be in the water. Paddlers and boaters can also hear about best practices from the Northwest Indiana Paddling Association (NWIPA) and the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG).

The event will also feature messages from a new regional water safety campaign with tips for steering clear of dangerous currents and waves. The Be Current Smart campaign encourages swimmers not to jump off structures or enter the water when waves are high. And parents are reminded to “be a water watcher” and keep a close eye on children while they’re in the water.

In addition to hosting Water Safety Day, the Southern Lake Michigan Water Safety Task Force will also participate in several Coastal Awareness Month events slated through June. The group, which was formed last year by IISG, includes representatives from Indiana’s Lake Michigan Coastal Management Program, Indiana Dunes State Park, USCG, NWS, IDEM, GLSRP and NWIPA, as well as officials and beach managers in several coastal communities.

April 28th, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

Swimmers, boaters, and anglers visiting Indiana’s coastline can once again learn about conditions in southern Lake Michigan with real-time data collected by the Michigan City buoy. The buoy, launched for the first time in 2012, returned to its post four miles from shore today to collect data on wave height and direction, wind speed, and air and surface water temperatures.

The only one of its kind in the Indiana waters of the lake, the Michigan City buoy and its temperature chain helps anglers and boaters find fishing hot spots and identify the safest times to be out on the lake.

The only one of its kind in the Indiana waters of the lake, the Michigan City buoy and its temperature chain helps anglers and boaters find fishing hot spots and identify the safest times to be out on the lake.

Scientists at the National Weather Service in northern Indiana will also use wave height and frequency data collected throughout the season to better anticipate the locations of strong waves and currents that cause dangerous swimming conditions. Real-time data on nearshore temperatures and wave characteristics is also vital for research on fisheries and nearshore hydrodynamics.

Data will be available on IISG’s website until the buoy is pulled out for the winter in mid-October. The site shows snapshots of lake conditions—updated every 10 minutes—as well as trends over 24-hour and 5-day periods. Buoy-watchers can also download raw historical data at NOAA’s National Data Buoy Center.

And starting later this season, our website will also relay data collected by a new environmental sensing buoy placed north of Chicago. In addition to allowing people to track waves and temperatures, the data collected by this buoy could also help officials warn beachgoers when contamination levels may make swimming unsafe.