December 11th, 2018 by IISG

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) is excited to announce the funding of five new Discovery Projects. These small, one-year projects help researchers achieve bigger and better things, such as larger grants to study critical questions, providing proof of concepts that can be scaled up to support labs or businesses, or generating tools to help communities make the best use of available information. The five projects IISG began funding in 2018 address aquaculture, aquatic invasive species and pollution.

“These five new research projects are asking questions that are highly relevant to aquatic systems in Illinois, Indiana, Lake Michigan and the broader Great Lakes region,” said IISG Director Tomas Höök. “We have great hopes that these Discovery Projects will indeed springboard their principal investigators to other opportunities and outcomes.”

Aquaculture

Karolina Kwasek of Southern Illinois University-Carbondale will explore whether invasive Asian carp could be used to feed very young largemouth bass raised in aquaculture facilities. Largemouth bass are a popular species across the country, but their high protein requirements make them tricky to rear. Kwasek hopes this novel use of Asian carp may support aquaculture growers who wish to raise largemouth bass.

Invasive Species

Eric Larson of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign will use a relatively new concept, that of an avatar species, to predict where a new invasive species might establish. He will use the red swamp crayfish, which is already found in the Great Lakes basin, as an avatar to predict where another potential invader, Chelax destructor, might successfully establish. If successful, this method could potentially be applied to other potential invaders, including fish, aquatic plants, and other macroinvertebrates.

Pollution

Jen Fisher of Indiana University Northwest will investigate whether pollution from failing septic systems might be affecting microbial communities on beach sand, ultimately posing a risk to human health. Her work will be focused in northeast Indiana.

An Li of the University of Illinois at Chicago will assess presence of microplastics in Lake Michigan sediments using samples that have been previously collected and analyzed for other contaminants. Through this work, she hopes to generate protocols that can be applied to sediments in any aquatic system.

John Scott of the Illinois Sustainable Technology Center will examine whether microplastics help introduce per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) to the lower levels of aquatic food webs. His timely work has the potential to affect fish consumption advisories, if it seems likely that PFAS can be transferred up the food web.

May 2nd, 2018 by iisg_superadmin

University research projects often include an opportunity for a few students to get real-world field or laboratory experience. At Loyola University Chicago’s Micro Eco Lab, biologists Tim Hoellein and John Kelly have often found ways to connect students with their work. But when they set out to implement the lab’s recent Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant project, opportunities for students really took off.

To accomplish this ambitious, comprehensive study to assess microplastic levels in Lake Michigan waterways efficiently and timely, Hoellein and Kelly brought on a post doc to oversee the project. Rachel McNeish looked to students to get much of the work done and the pool of helpers grew to dozens—35 in all, including graduate, undergraduate, and high school students.

“Students were involved with fieldwork, sampling and processing,” said McNeish. They did all the lab work, including data curating—making sure it was entered correctly. Some students have been in charge of specific aspects of the process, making sure it is happening as it should. They then have an opportunity to take a portion of the dataset, analyze it, and present it on campus or at professional conferences.”

For Masters student Lisa Kim, her time spent working on microplastic research and outreach turned out to be life changing. She started her undergraduate tenure at Loyola as a pre-med student, but changed directions after her experience working on the Sea Grant project. “I really fell in love with lab work—getting samples and processing them, and then data analysis and even presenting the results on campus,” said Kim.

She is now an author on the first journal article from the IISG microplastic study, which thus far has found plastic microfibers in the water, sediment and fish in three main Lake Michigan rivers.

Kim is also working on her own research and is exploring opportunities to engage in outreach and in the policy process. “I really want to communicate information about microplastic pollution with everyone. I feel like I got experience working in the lab and doing research, but now I want to bridge the gap between scientists and the community.”

The students come from diverse backgrounds, including some who are first generation college students, and bring a range of interests and experiences. Many are new to the tasks at hand.

“My first time in the field was quite the challenge, balancing being in the canoe with sediment samples and other heavy equipment, all while trying to collect different types of samples from the water,” said Melissa Achettu, a Loyola junior.

Achettu, who has now been working on the IISG project for 18 months, has been funded by two Loyola fellowships to help with the study and to present findings at an international conference this spring.

With Loyola’s setting in Chicago, some students are also experiencing nature and camping for the first time. And with such a busy lab, they are developing leadership skills and learning to work together.

“I enjoy working in the lab with so many other students because it’s a great learning experience when people of so many backgrounds come together,” said Achettu. “Everyone has their unique inputs and ideas. We all learn patience, teamwork and communication skills.”

McNeish puts herself in that camp. “Undergraduate students have just been phenomenal the whole time I’ve been doing research and throughout my education,” she explained. “I feel like I can teach them many things, but they can also teach me a lot too. It’s a two-way learning system. And working with a large group, everyone has something to learn.”

As the research wraps up, McNeish herself is moving on to a new opportunity. She will start a tenure-track faculty position at California State University Bakersfield this August where, as a freshwater scientist, she plans to develop her own student-focused research program.

December 3rd, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

Residents of Illinois, Indiana, and the broader Great Lakes region will benefit from new IISG research. Altogether, the four, two-year projects will receive more than $780,000 starting in 2016.

Residents of Illinois, Indiana, and the broader Great Lakes region will benefit from new IISG research. Altogether, the four, two-year projects will receive more than $780,000 starting in 2016.

John Kelly, a Loyola University biologist, will survey eight major rivers around the lake to trace the origins of microplastics pollution and what river characteristics—such as

surrounding land use or nearby wastewater treatment plants—may be driving this.

Purdue University’s Zhao Ma will lead an interdisciplinary team that seeks to reduce nutrients, sediment, and E. coli contamination in southern Lake Michigan. The team will use models to assess best management practices (BMP) for reducing runoff and the willingness of individuals to implement these BMPs. Looking at these two approaches together will allow them to optimize the best courses of action to reduce overall pollution.

A project led by Sara McMillan, who studies biogeochemistry and hydrology at Purdue University, will examine drainage ditch design from multiple perspectives. McMillan will compare designs that improve long-term stability and ecological effectiveness.

And Beth Hall, Midwestern Regional Climate Center director, will work with Paul Roebber of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee to improve how flash flooding events in urban centers are predicted and communicated. Hall and Roebber’s project is partially funded by Wisconsin Sea Grant.

July 21st, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

Illinois may be hundreds of miles from the Gulf of Mexico, but it’s a key contributor to the “dead zone,” a section of water the size of Connecticut devoid of oxygen that forms every summer. The culprit is millions of pounds of nutrients from farm fields, city streets and wastewater treatment plants entering the Gulf each year through the Mississippi River system.

Now, the state has just released a plan—the Illinois Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy—to keep those nutrients out of the water.

The collaborative effort began almost two years ago in response to the federal 2008 Gulf of Mexico Action Plan, which calls for all 12 states in the Mississippi River Basin to develop plans to reduce nutrient losses to the Gulf. The process was spearheaded by the Illinois EPA and the Department of Agriculture and facilitated by Illinois Water Resources Center (IWRC) and Illinoi-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG).

The collaborative effort began almost two years ago in response to the federal 2008 Gulf of Mexico Action Plan, which calls for all 12 states in the Mississippi River Basin to develop plans to reduce nutrient losses to the Gulf. The process was spearheaded by the Illinois EPA and the Department of Agriculture and facilitated by Illinois Water Resources Center (IWRC) and Illinoi-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG).

“It’s the most comprehensive and integrated approach to nutrient loss reduction in the state’s history,” says Brian Miller, director of IISG and IWRC. “But what really sets the plan apart is how it was developed. Government agencies, agricultural producers and commodity groups, non-profit organizations, scientists, and wastewater treatment professionals were all at the table working together to create this strategy.”

The approach outlines a set of voluntary and mandatory practices for both urban and agricultural sources for reducing the primary drivers of the algal blooms that lower oxygen levels—phosphorus and nitrogen. By targeting the most critical areas and building on existing state and industry programs, these practices are expected to ultimately reduce the amount of nutrients reaching Illinois waterways by 45 percent.

Led by researchers at the University of Illinois, the study uncovered numerous cost-effective practices for reducing nutrient losses. At the heart of the strategy is a scientific assessment that used state and federal data to calculate Illinois’ current nutrient losses and determine where they’re coming from.

The plan for wastewater treatment plants is relatively straightforward. The state had already begun to cap the amount of phosphorus they are allowed to release, restrictions that will likely be expanded under the new plan. The strategy also calls for sewage plants to investigate new treatment technologies that could lower phosphorus levels enough to prevent algal blooms in nearby waterways.

For farmers and others working in agriculture, the options are a little broader. Most of the recommended practices, such as installing buffer strips along stream banks to filter runoff, planting cover crops to absorb nutrients and adjusting nitrogen-fertilizing practices have been used successfully in Illinois for years.

“There is no silver bullet for reducing nutrients,” said Mark David, a University of Illinois biogeochemist and one of the researchers behind the scientific assessment. “It is going to take at least one new management practice on every acre of agricultural land to meet the state’s reduction goals.”

June 10th, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

Victoria Figueroa is a summer intern with IISG. She is on the University of Illinois campus, working with Eliana Brown, stormwater specialist. She will be engaged in raising awareness about the benefits and beauty of rain gardens.

A Chicagoan born and raised, I was not used to being surrounded by so much green. There are plenty of parks in the city, but you never feel like you are surrounded by nature. But when I moved to Urbana for school, I realized just how much of a city kid I was and how much I could enjoy being surrounded by so much green, in particular trees. One night, walking around campus with a couple friends, we thought we would try our luck at climbing trees. This may not have been the best idea as it was dark and the two big (oak, I later learned) trees were surrounded by rocks and overgrown shrubs. But the light coming from the detention pond not too far away was enough to give us the confidence to try.

Now I didn’t succeed, but what was once just a meaningless patch of land on my campus, became a memory I now have a great fondness for. Just imagine my surprise when I learn that those rocks and shrubs I was playing in were not just there for decoration. Those stones and plants were not just there as placeholders. That night my friends and I had played in a rain garden. Our amusement might not have been the use the gardeners and students who built the garden had in mind, but it was very natural.

But what is a rain garden? A rain garden is built in a bowl shape, which gives rainwater runoff from surfaces that do not absorb water, like roofs, sidewalks, and roads, the opportunity to be absorbed. This helps to control flash floods, remove pollutants, improve water quality, and recharge groundwater. Not only do these gardens provide wildlife habitats, but are also an attractive alternative to detention ponds and can be adapted to fit into the existing urban landscapes. This is why it was so easy to walk through a rain garden on my college campus. It did not feel out of place. It was not intrusive and blended well in between the dorm building and its surroundings.

Rain gardens are a relatively new approach to treating stormwater runoff. Stormwater runoff is any water originating from rainfall or melted ice or snow. Stormwater runoff not only transports pollutants, but is also a creator of pollution itself. A study conducted by the Environmental Protection Agency from 1979-1983 found that stormwater runoff contributed to poor water quality in receiving streams. This can be particularly harmful in urban areas because of the great amount of hard surfaces like roads, walkways, and parking lots that do not allow water to be absorbed. This then causes a larger percentage of stormwater runoff than in more rural areas. Therefore it is important for urban areas to be able to manage the excess water that comes along with living in our concrete jungles. Rain gardens were created to mimic natural water retention areas, which existed before the development of urban environments and they began to be developed for residential use in 1990.

There are many ways of going about treating water in urban areas, and rain gardens are a good way to start. They are unassuming and they can be implemented in your own yard. Not only are rain gardens helpful but they can very beautiful as well. Like any garden, its appearance can vary. It really depends on what the gardener makes of it. Rain gardens could have more plants that resemble grass and be very subtle or many blossoming plants and add more color to their yard.

Maybe one day I’ll have one in my own back yard. But first I invite you to follow me in my future blog posts as I search for the perfect fit for my future garden, whether I keep Chicago as my home or move away and settle down elsewhere.

November 17th, 2014 by iisg_superadmin

Microbeads have attracted a lot of public and political attention in the Great Lakes region since Sam Mason and her lab first discovered the tiny beads in staggering numbers in lakes Huron, Superior, and Erie in 2012. Since then, sampling excursions on the remaining lakes—conducted with help from Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant and 5 Gyres—have turned up similar findings.

In many ways, the results of these studies raise more questions than they ask. One of the most important, though, is “What effect do microbeads and other plastic pollutants have on Great Lakes food webs and ecosystems?” Research into this question has only just begun, but years of studies in the oceans provide some insight. Some of these latest findings come from our friends at South Carolina Sea Grant.

From Coastal Heritage:

John Weinstein is studying how grass shrimp (Palaemonetes pugio) respond to a diet of plastic beads. A crustacean about the size of half of a shelled peanut, a grass shrimp consumes microalgae that grow on plant detritus—especially decomposing saltmarsh stems called “wrack”—along estuaries and coasts, but it’s also a predator on a wide variety of small animals.

Because of its abundance, sensitivity, and ecological importance in southeastern U.S. estuaries, the grass shrimp is often used to study the effects of pollution in the field and laboratory.

In Weinstein’s lab, Austin Gray, a graduate student in biology at The Citadel, has been feeding grass shrimp two types of beads: one a bright green and the other one translucent.

The green beads are polyethylene, the type of plastic used in plastic bags, bottles, plastic wrap and other films for food preservation, and many other products. Polyethylene is the most common type of plastic found in marine debris around the world.

The translucent beads are polypropylene, a type of plastic used in bottle caps, candy- or chip-wrappers, and food containers. Polypropylene is the second most common type of plastic found in marine debris.

In a lab dish, Austin Gray deposits translucent 75-micron beads. But a visitor looks in the dish and can’t find a single bead. Under the dissecting microscope, though, dozens of tiny spheres suddenly appear. To put it in perspective, an item at about 40 microns is the width of two spooning human hairs.

Gray fed 16 grass shrimp a diet of brine shrimp mixed in with plastic beads. Each grass shrimp was isolated in water that was changed every other day. Eight animals were fed polyethylene beads and eight were fed polypropylene beads. After six days, all of the 16 shrimp were dead.

Dissecting the animals, Gray found plastic beads in their guts and gills. One individual had 10 tiny beads in its gut and 16 in its gills.

The gut blockages, though, were deadlier. The grass shrimp could still take in water through their partly blocked gills. But they stopped eating with clogged guts—or couldn’t eat—and died.

“In my mind,” says Weinstein, “it’s consistent with starvation. The more particles in guts, the more quickly the grass shrimp die.

Concern about results like these has led Illinois to become the first state to ban the sale of microbeads in personal care products. The law, passed in June, is slated to take full effect in 2019. Similar legislation has also been considered in New York and California.

Click on the link above to read the full article.

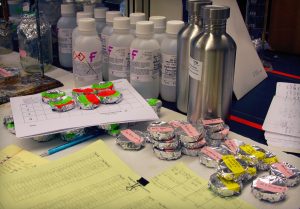

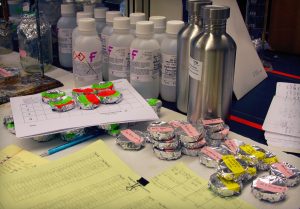

***Photo: Collecting plastic samples in southern Lake Michigan in 2013.

September 23rd, 2014 by iisg_superadmin

Indiana communities along Lake Michigan are celebrating this year’s SepticSmart Week, Sept. 22-26, by reminding homeowners of the importance of septic system maintenance to environmental and public health.

Indiana communities along Lake Michigan are celebrating this year’s SepticSmart Week, Sept. 22-26, by reminding homeowners of the importance of septic system maintenance to environmental and public health.

An estimated 60,000 households in Lake, Porter, and LaPorte counties depend on septic systems to treat wastewater. Without regular maintenance, these systems can backup or overflow, contaminating nearby lakes, rivers, and groundwater supplies with everything from excess nutrients to E. coli to pharmaceutical chemicals. Septic system failures are also one of the primary causes of beach closures in Indiana.

To prevent failures, U.S. EPA and the Northwest Indiana Septic System Coordination Work Group has some advice for homeowners:

-

Protect it and inspect it: Have your system inspected every three years by a licensed contractor and have your tank pumped when necessary, typically every 3-5 years. Many septic system failures occur during the holiday season, so be sure to get your system inspected and serviced now before inspectors’ schedules fill up around the holidays.

-

Think at the sink: Avoid pouring fats, grease and solids down the drain. These substances can clog pipes and the drain field.

-

Don’t overload the commode: Only put things in the drain or toilet that belong there. Coffee grounds, dental floss, diapers and wipes, feminine hygiene products, cigarette butts, and cat litter can clog and damage septic systems.

-

Don’t strain your drain: Be water efficient and spread out water use. Fix plumbing leaks and install faucet aerators and water-efficient products. Spread out laundry and dishwasher loads throughout the day. Too much water at once can overload a system that hasn’t been pumped recently.

-

Shield your field: Remind guests not to park or drive on the drain field, which could damage buried pipes or disrupt underground flow.

The Northwest Indiana Septic System Coordination Work Group brings together federal, state, and local governments and agencies, state and county health departments, and not-for-profits to provide homeowners with information and assistance on the proper care of septic systems. IISG’s Leslie Dorworth has been a part of the group since it began in 2012. For more information or to get involved locally, contact Dorreen Carey at the Indiana DNR Lake Michigan Coastal Program at 219-921-0863 or dcarey@dnr.in.gov.

SepticSmart Week is part of U.S. EPA’s year-round SepticSmart program. In addition to educating property owners, the program is an online resource for industry practitioners, local governments and community organizations that provides access to tools to educate clients and residents.

September 11th, 2014 by iisg_superadmin

Laura Kammin, our pollution prevention specialist, has some exciting news. Let’s let her tell you about it:

If you only had a minute, what would you say?

Just one minute to explain what pharmaceutical waste is and how people can help reduce it. That was the challenge posed by our new pollution prevention team members Erin Knowles and Adrienne Gulley.

Challenge accepted! Here it is, the first installment of the Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant Pollution Prevention Minute.

We know it’s a long name. But don’t worry, the content isn’t. They’re one—ok, maybe sometimes closer to two—minute videos that give easy-to-understand answers to some of the more complicated questions surrounding the use, storage, and disposal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products.

Why videos? We are always getting asked questions like “what happens to the medicine that gets collected?” and “what are microbeads?” We think these new videos are a fun way to share the answers.

And be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel and watch for the next episode of IISG’s Pollution Prevention Minute.

November 11th, 2013 by Irene Miles

Recent research on Great Lakes contaminants has shown that microplastics – small beads of plastic used in many exfoliants, toothpastes, and other products – are contributing to pollution levels. As a result, mayors near the Great Lakes are calling on manufacturers to remove the plastics from their products.

From TheObserver.ca:

“The Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative, representing more than 100 Canadian and U.S. cities, is urging industry and governments to have microplastics removed from personal care products.

Its call came as a study on microplastic pollution was published based on sampling last summer on Lake Huron, Erie and Superior led by Sherri Mason, a professor at the State University of New York at Fredonia.

‘It takes that kind of initiative to get things to change,’ she said of the mayor’s support for the issue.

‘It’s not so much about cleaning it up, as it is about stopping it at its source.’

Mason returned to the lakes for seven weeks this summer to collect more samples, including one from the St. Clair River at Sarnia that will be analyzed as the study continues.

Samples taken in 2012 included green, blue and purple coloured spheres, similar to polypropylene and polyethylene microbeads in consumer products, such as facial cleaners.”

Read the complete article at the link above.