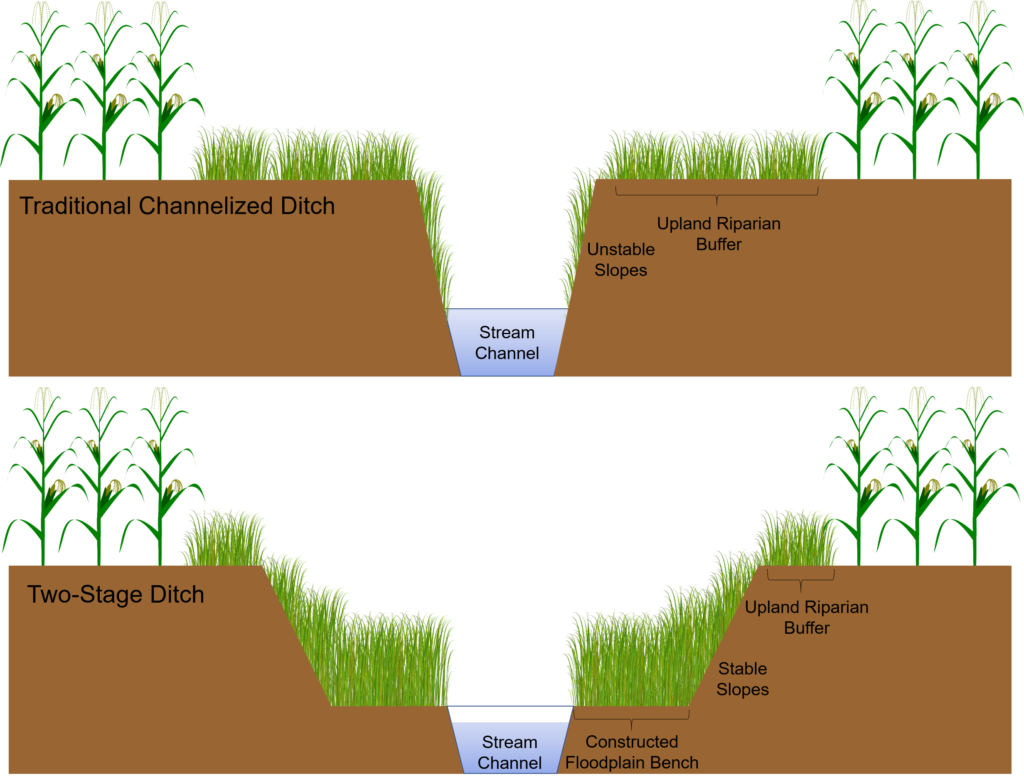

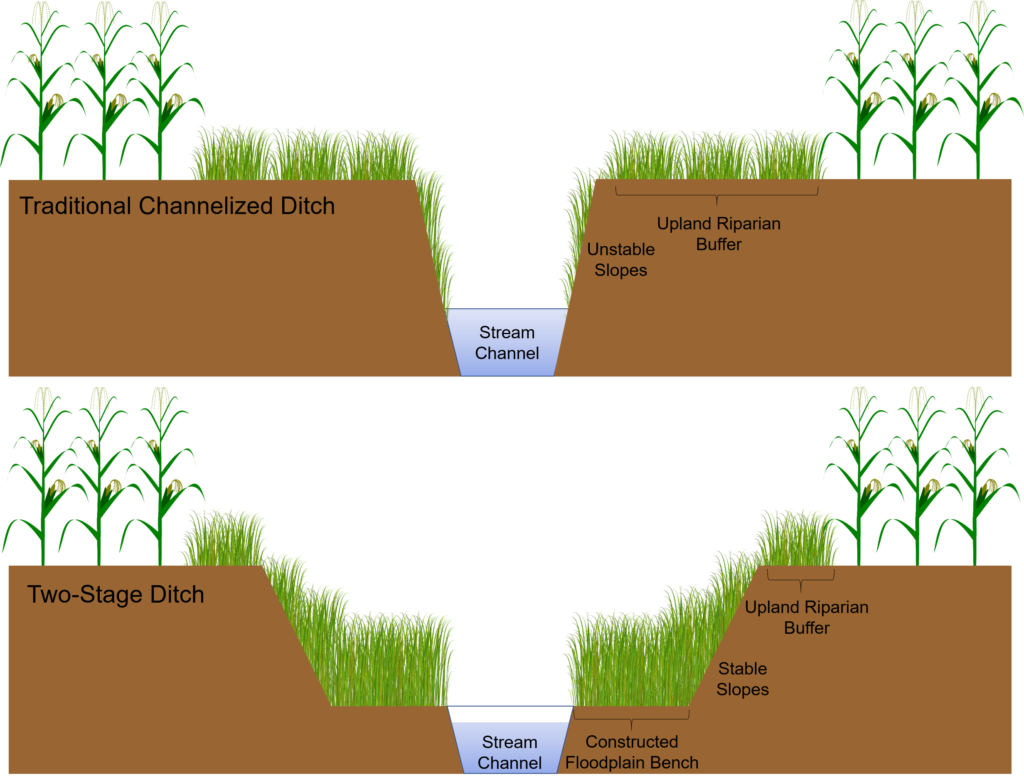

Waterways along Midwestern farmlands are typically managed to move stormwater away from crop fields quickly, but this efficient process can wash nutrients and sediment into lakes and rivers, nearby and downstream. Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant researchers have found that a change in waterway management practices can lead to a win-win—water is still quickly drained from crops with two-stage ditches, but because they have more floodplain area, stormwater slows down so more nitrogen is retained along the way.

Sara McMillan at Purdue University and Jennifer Tank at University of Notre Dame are monitoring nitrogen and phosphorus loads coming from two-stage ditches in farmland waterways to document how effective restored floodplains are at holding nutrients in place. “By restoring mini-floodplains on each side of these formerly channelized ditches, you add the potential for enhanced biology and hydrology to cleanse the water through nutrient and sediment removal,” said Tank, whose primary work is in ecology and environmental biology.

“Floodplains provide a way for water to spread out and slow down—allowing sediment to accumulate and plants and soil microbes to thrive. When plants thrive, this allows organic matter in the soil to increase,” said McMillan. In this environment, microbes use nitrogen for energy, removing it from the water as they transform it into a gas—a process called denitrification.

(Graphic courtesy of Brittany Hanrahan)

Brittany Hanrahan, whose doctoral research at Notre Dame was a part of this study, compared the effectiveness of reducing nitrogen in two-stage ditches with waterways in which traditional channelization management has stopped for at least a decade. Over time, these channels in northern Indiana developed mini-floodplains and began to look like more natural streams. The two-stage ditches in the study were about 10 years old.

Hanrahan, who now has a postdoctoral position with the USDA Agricultural Research Service, found that denitrification was 30 percent higher along two-stage floodplains compared to the naturalized ones. The two-stage ditches have more floodplain area than the naturalized channels and are designed to flood more often, which allows denitrification to happen more frequently.

“We calculated that it would take nearly 30 years for the floodplain in the naturalized ditch to accumulate the surface area of floodplain that is constructed in just one day in the two-stage ditch,” said Hanrahan. “Jump-starting the biology with two-stage construction really helps to remove more nitrogen even immediately after construction.”

While slowing down floodwater is conducive to denitrification, phosphorus goes through a different biological process. In fact, if floodwater stands long enough, phosphorus may be released from particles in the soil and water. On the other hand, creating space for water to spread out and slow down can enhance the settling of sediment particles with phosphorus attached.

The design of the two-stage ditch, including the height and width of the floodplain, can make a difference in terms of flooding frequency and duration. One general practice, according to McMillan, is to triple the width of the channel—if it is a 10-foot wide channel, 10 feet are added on either side so it is 30 feet wide.

“We’re pretty confident from previous research that it takes a long time for phosphorus to be released, so it’s not likely that we’re causing a net release of phosphorus that is stored in soils,” said McMillan, who is in Purdue’s Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering. “While we think that these ditches pose a net benefit for both phosphorus and nitrogen, phosphorus is indeed more complicated.”

Most two-stage ditches can be found in Indiana, which may be because the USDA Environmental Quality Incentives Program covers the majority of the cost of installing them in the state. It’s a one-time construction cost, whereas dredging to maintain trapezoidal channels needs to happen every few years, depending on the system. “With a two-stage ditch, the velocities in the main channel, which is the original channel, are fast enough during high flows that it is always self-cleaning,” said Tank. “You never have to dredge again.”

DECATUR, IL–As part of the state’s on-going commitment to reduce nutrient losses, the directors of the Illinois Department of Agriculture (IDOA) and Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced today the release of the state’s Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy Biennial Report. This document, unveiled at the 2017 Farm Progress Show in Decatur, Illinois, describes actions taken in the state during the last two years to reduce nutrient losses and influence positive changes in nutrient loads over time.

The Illinois Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy (NLRS) is one of many state strategies developed and implemented over the 31-state Mississippi River basin that are intended to improve water quality. Illinois’ strategy provides a framework for reducing both point and non-point nutrient losses to improve the state’s overall water quality, as well as that of water leaving Illinois and making its way down the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico.

“Illinois agriculture has a positive story to tell,” said IDOA Director Raymond Poe. “We have seen a significant increase in the adoption of various best management practices. Our partners and stakeholders have done a tremendous job getting the word out about what we are doing in Illinois with the Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy. Farmers understand the consequences of nutrient loss, and they support our quest to minimize losses.”

“In just two years, we are already seeing the impacts of Illinois’ strategy on water quality,” said Illinois EPA Director Alec Messina. “The collaborative efforts of our stakeholders are resulting in real improvements in Illinois’ waters and we look forward to future improvements that will be gained as additional practices are implemented.”

The biennial report contains an update to the original science assessment including nutrient load data from 2011–2015 for both point and non-point sources as well as sector-by-sector reports on activities conducted during the last two years targeted at nutrient loss reduction.

The report also contains information from a recent survey conducted by the United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service as well as data from other existing sources to serve as metrics to measure progress towards overall water quality improvements now and in the future.

The Agriculture Water Quality Partnership Forum (AWQPF) reports that the agricultural sector invested more than $54 million in nutrient loss reduction for research, outreach, implementation and monitoring. These contributions have come from AWQPF members and other organizations that are working towards reaching the goals set forth in Illinois NLRS. Because of the proactive measures of various agriculture groups, Illinois farmers have become broadly aware of a variety of strategies that mitigate nutrient loss through the adoption of best management practices. Highlights include a move toward split spring and fall nitrogen applications and an increase in the number of acres dedicated to conservation practices such as a use of cover crops.

Since the release of the strategy two years ago, significant strides have also been made in limiting the amount of phosphorus discharge from wastewater treatment plants in Illinois. In the last year, point source sector members targeted key decision makers and practitioners to spread the message of nutrient loss reduction through regulatory updates as part of the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) program. As of 2016, nearly 80 percent of all effluent from wastewater treatment plants in Illinois is regulated under a NPDES permit that includes a total phosphorus limit. This number will continue to grow as existing permits expire or come up for renewal. To demonstrate the commitment toward nutrient removal, wastewater treatment facilities report spending $144.96 million to fund feasibility studies, optimization studies and capital investment.

Illinois EPA, through its State Revolving Fund program, provides low interest rate loans to point-source projects addressing water quality issues, including nutrient pollution. Last year, Illinois EPA provided or granted $640,599,148 dollars to these projects. Illinois EPA also provides funding for nonpoint source projects designed to achieve nutrients reduction. Annually this program provides $3.5 million to nonpoint source projects.

“What’s made NLRS remarkable is that we had a broad suite of stakeholders that came together to work on the strategy, and they brought not only their ideas, but the support of their organizations. They all got behind it,” said Brian Miller, Illinois Water Resources Center (IWRC) and Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) director. “It started with a science assessment from the university that identified problems and potential solutions. Working together we’re already starting to see some successes.”

This report, which was facilitated by IWRC and IISG, will be updated again in 2019. The science, monitoring and activity from each sector will be updated to demonstrate Illinois’ continued commitment to nutrient loss reduction.

“There is a lot more work that needs to be done,” said Warren Goetsch, IDOA deputy director. “However, in releasing this report at the Farm Progress Show, we are introducing these successes to farmers who may be somewhat apprehensive about trying new management practices. Increasing the exposure of our message will keep this effort in front of producers so we can continue to make progress in the years to come.”

This article is based on a press release from IDOA and Illinois EPA. Contacts are Rebecca Clark (217) 558-1546 and Kim Biggs (217) 558-1536.