Lately, Sheboygan is on the upswing. This city in Wisconsin that sits along the Sheboygan River is booming with new housing, more tourism, and more water-based recreation opportunities, according to a recent Great Lakes Commission study. Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG), as part of a team of partners, provided expertise that contributed to this success story.

Not so long ago, the river was considered a black eye on the community. Labeled one of the most polluted rivers in the country, it was contaminated with an alphabet soup of PCBs and PAHs. With funding from the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, approximately 300,000 cubic yards of contaminated sediment (or 15,000 full dump trucks) were removed from the river in 2012-2013. As a result, river-goers enjoy a deeper river with better navigation and access, and a cleaner habitat for fish and wildlife to thrive.

“There’s no question in my mind that if that cleanup effort hadn’t gone on, we would not see the kind of development and enthusiasm going on in our community,” said Adam Payne, Sheboygan County administrator. “It absolutely triggered a lot of the good things that are in play.”

As is typical for projects funded through the Great Lakes Legacy Act, partners were key to its success, including federal, state, local—agencies, non-for-profits, private companies—the list is extensive. “The level of collaboration and teamwork was unprecedented of anything I had seen in my career,” added Payne.

For its part, IISG funded research to assess the economic impact of the contaminated river on housing prices. “We looked at actual sales of single family houses in the area from 2002-2004,” explained John Braden, University of Illinois economist (now retired). “And we surveyed 850 residents to understand people’s perceptions of the river, and their willingness to pay more for housing if the river was cleaned up.”

Braden found that property values for homes within five miles of the contaminated waterways were significantly depressed—an 8 percent discount, on average. This research and related Sea Grant outreach helped illustrate the value of the cleanup, helped to keep the Sheboygan community informed about the remediation process as it happened, and helped to change the conversation about sediment remediation.

“Sediment remediation is very expensive, so how can we justify these multi-million dollar projects?” said Caitie Nigrelli, IISG social scientist. “The main goal is to improve environmental quality of water resources, but if we understand more of the benefits, we can make a better case for these projects.”

Nigrelli worked with a Sheboygan outreach team in 2012 to provide information to stakeholders and the public. She helped convey the results of Braden’s research in her outreach efforts through publications and other venues. In addition, bringing her social science expertise to the project, she oversaw a study to bring community perceptions to light to better understand how to communicate about the sediment remediation project and its benefits to the public.

“We found that while the river was viewed as an asset, it had a negative stigma,” said Nigrelli. “Our interviews before the remediation revealed that residents saw the water as unclean and some were hesitant and even afraid to come in contact with the water.”

Due to years of sedimentation, the depth of Sheboygan River was also viewed as a major concern as its shallowness limited access for larger boats and sailboats. While the point of the remediation was to remove contaminants, a side benefit was an increase in river depth. These and other findings helped Nigrelli and the outreach team target public information to address specific concerns.

Payne describes the value of a well-informed public in terms of just getting through the remediation process. “To put it in perspective, when we were removing the contaminated soil from the river and harbor, we had trucks coming and going through the heart of the city every three to five minutes, 24/7. That’s disruptive, lots of dust, noise, traffic and that obviously raises folks eyebrows and raises concerns. I think where outreach efforts were so helpful is in raising awareness with the public—these potential benefits are why we are going to go through this.”

To learn more about remediation partnership possibilities, “A Seat at the Table: Great Lakes Legacy Act” is a new video that explains what it means to be a cost-share partner with the Environmental Protection Agency under GLLA. The video uses interviews with partners to describe the benefits and challenges of cost-share partnering, the cost-sharing mechanism, examples of in-kind services and the flexibility of partnerships.

To see what successful partnerships can accomplish, follow Nigrelli (@Gr8LakesLady) on Twitter as she has been sharing 22 sediment site success stories, including before and after photos, contamination causes, partnerships and cleanup details. Follow and join the conversation using #22SedimentStories.

.jpg) We recently got some exciting news from former intern Ada Morgan, who in 2011 worked with Caitie McCoy on a study of community perceptions of sediment remediation in the Sheboygan River Area of Concern. We’ll let her tell you what she has been up to since.

We recently got some exciting news from former intern Ada Morgan, who in 2011 worked with Caitie McCoy on a study of community perceptions of sediment remediation in the Sheboygan River Area of Concern. We’ll let her tell you what she has been up to since.“The Sheboygan study finished up just before I graduated from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. I studied economics and environmental geology there, and I knew I wanted to continue my studies in the environmental field. I was encouraged by Caitie and a few others I looked up to to look into graduate school. That fall, I began a master of urban planning and policy program at the University of Illinois Chicago, where I continued to learn about how humans interact with our environment and how to think holistically about the decisions we make.

My specialization was in environmental planning. I took some great courses, like an economic and environmental planning course and a course on residential sustainability policy. My final project centered on greywater reuse in a south suburb of Chicago.

I graduated this past May and am now the environmental and sustainability coordinator for a bread manufacturing company. I started just a few weeks ago. I am responsible for both environmental compliance (permits, etc.) and sustainability projects and initiatives. My main task so far has been re-developing an environmental management system for the entire company, which has four different facilities.

My experiences working with Caitie at IISG was the best preparation I could have had for both graduate school and my current job. I was able to participate in almost all aspects of the Sheboygan study. I helped with interviewing stakeholders, performed data analysis, and co-authored the final report with Caitie. You don’t often get this kind of hands-on experience with qualitative analysis and reporting in school.

I also learned a lot about environmental regulations since the project I worked on was under EPA’s Great Lakes Legacy Act. Understanding the regulatory structure helped tremendously while I was in the urban planning program (reading codes) and continues to help me navigate compliance issues at my company. Overall, the time I spent at IISG was one of my most valuable internships, and I am extremely thankful to have had the opportunity to work at such a fantastic organization.”

Residents of Sheboygan, Wisconsin are seeing their namesake river, and the opportunities it holds for the community, in a whole new light thanks to a suite of cleanup projects completed in 2012 and 2013. For decades, high concentrations of PCBs and other industrial pollutants lining the riverbed had kept river-goers and businesses at arm’s length. But with the contaminated sediment removed and habitat restoration well underway, the public is embracing the river with full force.

“After nearly three decades of being a black eye of the community, we are thrilled that the Sheboygan River and harbor is being restored to reduce health risks to people, fish, and wildlife, and will greatly enhance opportunities for economic development,” said Adam Payne, Sheboygan County Administrator at a 2012 press event celebrating the project.

“After nearly three decades of being a black eye of the community, we are thrilled that the Sheboygan River and harbor is being restored to reduce health risks to people, fish, and wildlife, and will greatly enhance opportunities for economic development,” said Adam Payne, Sheboygan County Administrator at a 2012 press event celebrating the project.

Perhaps the biggest boost so far has been to recreation. Dredging the equivalent of 15,000 dump trucks of contaminated sediment left boaters and anglers with a deeper river that is easier to access and navigate. With the contamination gone, the community has also started to see the Sheboygan River as a safe place to spend an afternoon. Just a few months after the project ended, residents reported seeing more and bigger boats navigating in and out of the river’s harbor, and they expect to see even more fishing and boating in the coming years.

“Anytime you have a healthy river going through a community, you have a better quality of life,” said one resident to IISG’s Caitie McCoy and Emily Anderson as part of a series of interviews about how community perceptions of the river had changed.

The deeper, cleaner river has also attracted local businesses. Everything from coffee shops to digital communications companies have opened along the river, and more businesses are expected to follow. It is too early to say just how much the cleanup project will impact things like property values, tourism, and redevelopment, but it is already clear that riverfront development is on the rise thanks to changes to the river and its newly restored status within the community.

“When it comes right down to it, those who would invest in the river and want to develop this property, they are really after the water access,” said another resident.

There is good news for local wildlife too. With the dredging work completed, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and other project partners have begun work to restore native habitats. Recently planted native plants have caught the attention of a variety of species, including cranes and blue birds. With this work done, the Sheboygan River will officially be taken off the list of most polluted places in the Great Lakes.

There is good news for local wildlife too. With the dredging work completed, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and other project partners have begun work to restore native habitats. Recently planted native plants have caught the attention of a variety of species, including cranes and blue birds. With this work done, the Sheboygan River will officially be taken off the list of most polluted places in the Great Lakes.

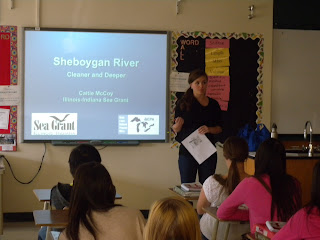

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant’s environmental social scientist Caitie McCoy informs and engages communities about important Great Lakes cleanup and restoration projects that affect them, and works with students to teach them more about Great Lakes ecology. One of her most recent opportunities to work with students was in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, where she provided information and lessons about a project close to home.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant’s environmental social scientist Caitie McCoy informs and engages communities about important Great Lakes cleanup and restoration projects that affect them, and works with students to teach them more about Great Lakes ecology. One of her most recent opportunities to work with students was in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, where she provided information and lessons about a project close to home.

Caitie writes, “I visited Sheboygan, Wisconsin last Tuesday and spoke to high school biology students, answering questions about the Great Lakes Legacy Act dredging project happening just two miles from their school. This was my final school to visit in Sheboygan as part of a 12-school, countywide tour, which began this past October and reached about 600 high school science students. Now the students know the purpose of a cleanup happening right in their downtown, and they understand the science behind it.

IISG is a collaborating member of Sheboygan’s ‘Testing the Waters’ program, through which students visit some of the Sheboygan River cleanup and habitat projects and learn techniques for testing water quality. My classroom visits helped set the stage for this program, and IISG also provided water sampling instruments for their use.

IISG is a collaborating member of Sheboygan’s ‘Testing the Waters’ program, through which students visit some of the Sheboygan River cleanup and habitat projects and learn techniques for testing water quality. My classroom visits helped set the stage for this program, and IISG also provided water sampling instruments for their use. Some of the specific topics that we discussed with students included the chemical qualities of the pollution, the effects that pollution has on the food web, and the cleanup process under the Great Lakes Legacy Act. I also spoke with them about habitat restoration projects, which are removing invasive species, creating natural, softened shorelines, and improving filtration of runoff.

This project is part of a larger effort to provide students with stewardship opportunities and supplemental hands-on education about remediation and restoration efforts throughout the Great Lakes. It has been great to work with students in Sheboygan and Northwest Indiana, and I look forward to bringing this program to more Great Lakes students soon.”For more information about Great Lakes educational programs and opportunities, visit our education page and follow our posts here on the blog.

.jpg)