Meet Our Grad Student Scholars is a series from Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) celebrating the graduate students doing research funded by the IISG scholars program. To learn more about our faculty and graduate student funding opportunities, visit our Fellowships & Scholarships page. Jin Yi (Jeanie) Tan is a second-year student in the Pharmaceutical Sciences Doctoral Program at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). Her research is focused on developing an “environment to bioassay” antibiotic discovery approach while collaborating with local community centers—this is part of an educational effort to pair graduate-level research with outreach programs. As part of her work funded by Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, she has also trained in scientific diving to explore the capacity of bacteria derived from Lake Michigan to produce new antibiotic sources.

Across the globe, superbugs—bacteria or fungi known to cause infections—are on the rise. The antimicrobial resistance crisis has become one of the most significant threats to public health. Without mobilized efforts to discover new antibiotics, the World Health Organization estimates about 10 million deaths related to antimicrobial resistance will occur per year by 2050.

To address this, graduate student Jin Yi (Jeanie) Tan is focused on finding novel drug-leads to combat multi-drug resistant bacteria by harnessing the power of their natural enemy: other bacteria. For millions of years, bacteria have fought one another with specialized chemical weapons. As a result of this evolutionary antagonism, microorganisms are a major source of antibacterial drugs.

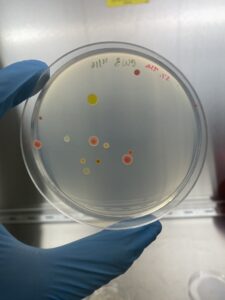

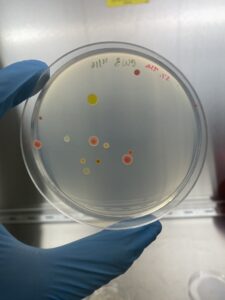

Bacteria colonies that will be examined for potential antibiotic drug leads. Photo credit J. Tan.

Studying in the laboratory of Brian Murphy, a medical chemist at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Tan has been developing a new environment to bioassay antibiotic discovery approach using robotics to rapidly select, screen, and prioritize prolific antibiotic-producing bacteria from the environment. This approach streamlines the front-end of microbial drug discovery by enabling most steps to be performed in a semi-automated fashion. In fact, parts of the process were conceptually simple enough for Tan to be able to teach them to middle school students.

Through support as an Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant Graduate Student Scholar, Tan’s work builds on a current IISG-funded initiative led by Murphy. Tan’s research is integrated with an educational outreach program in partnership with local community centers to bridge the gap that exists between universities and their surrounding communities.

One such partnership is with the James Jordan Boys and Girls Club of Chicago, an organization in a near west side neighborhood that is home to over 32,000 Chicagoans and houses groups that are predominantly underrepresented in STEM. The afterschool program, Chicago Antibiotic Discovery Lab, brings students along for a practical learning experience while they hunt for antibiotics in their own neighborhoods. Lessons go beyond the classroom to ignite a sense of curiosity in students to engage in STEM, as well as provide exposure to careers in the environmental and biomedical sciences.

Students from the James Jordan Boys and Girls Club of Chicago meet the robot that will help pick their bacterial colonies. (Photo provided by Jin Yi “Jeanie” Tan)

So far, the program has led and educated 19 students (6th to 8th grade) in multiple steps of Great Lakes-based antibiotic discovery. They have engaged in three different local sample collections from both land and water environments, which included sediment, plants, and swabs of various surfaces. Students completed multiple tasks related to their samples—instilling a sense of ownership over their results—and performed applied science experiments in parallel with their mentors. This includes 1) growing bacteria, 2) programming a robot to isolate them by the hundreds/thousands, and 3) testing the ability of each one to inhibit the growth of deadly pathogens. The ultimate goal is to identify a new antibiotic from one of the bacteria.

Back in the lab, Tan is working on the top three samples that have shown promising growth inhibition against Staphylococcus aureus, a human pathogen well-known for causing life-threatening clinical infections. She is using a combination of chromatography and spectroscopy to identify novel antibiotics. Tan plans to publish her results and make a blueprint of the program available for others to create or improve similar university-community partnerships.

Besides the samples collected by her students, Tan is particularly interested in exploring aquatic bacteria to find new chemistry to combat infectious diseases. The Great Lakes serve as an excellent resource for this discovery effort, and chances of finding novel molecules is dependent on the biodiversity present in these aquatic ecosystems. As part of her training, she has been certified for underwater microbial sample collection by SCUBA and plans to perform scientific dive expeditions in various parts of Lake Michigan for antibiotic discovery.

A student from the James Jordan Boys and Girls Club of Chicago collects samples from local waterways.(Photo provided by Jin Yi “Jeanie” Tan)

“I’m excited to start scientific diving this summer and to share my experience with students,” said Tan. “By understanding the bio-assets from Lake Michigan and promoting scientific knowledge about bacteria and their essential roles in medicine, we want to bring a different perspective on why it is critical to protect the region’s biodiversity.”

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a partnership between NOAA, University of Illinois Extension, and Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources, bringing science together with communities for solutions that work. Sea Grant is a network of 34 science, education and outreach programs located in every coastal and Great Lakes state, Lake Champlain, Puerto Rico and Guam.

Contact: Carolyn Foley

Not every day do students board a ship and learn about the research conducted out on Lake Michigan. Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) Community Outreach Specialist Kristin TePas recently organized tours of the U.S. EPA research vessel, the Lake Guardian, for 140 students and chaperones from four Illinois and Indiana schools.

Students from Chicago’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. College Preparatory High School boarded Lake Guardian just off Navy Pier with their science teachers Cheryl Dudeck and Melanie Yau, who in previous summers, completed a week-long shipboard science teacher workshop on the research vessel. Earlier in the day, Deb Broom’s class at Portage High School in Portage, Ind., and Marta Johnson’s students from South Shore International College Prep in Chicago toured the ship as well.

While aboard Lake Guardian, students learned from the ship’s crew about aquatic invasive species like quagga mussels in the Great Lakes, got a hands-on experience with research samples, and met the ship’s captain. The crew shared with students stories about life on the ship and demonstrated the equipment researchers use to monitor water quality on the lake. Paris Collingsworth, IISG Great Lakes ecosystem specialist, was on board to share some recent research findings.

Middle school students from Discovery Charter School in Porter, Ind., also joined their science teacher Amanda Renslow aboard the research vessel. In addition to the ship tour, Renslow’s students engaged in a beach cleanup at nearby Ohio Street beach. Students tracked each item of trash they collected for further discussions about recycling and sustainability back in the classroom.

Alongside the beach, Allison Neubauer, IISG Great Lakes outreach associate, led an activity for the Discovery School students to guess how long common items thrown in the trash, like juice containers and newspaper, take to break down in the environment.

For more information about the research vessel, including information about ongoing projects, visit Lake Guardian.

Allison Neubauer and Kirsten Walker were at the University of Illinois Public Engagement Symposium last week to raise awareness of IISG outreach in Champaign-Urbana. Allison had this to say about the event.

The public engagement symposium was a great opportunity to find out what other local organizations and academic programs are working on. The crowds of people—both those staffing booths and walking through and exploring—were a true testament to Champaign-Urbana’s widespread effort to get involved and take collective action on local initiatives.

Our IISG table generated a lot of traffic. With spring on the horizon, many visitors were excited to learn about our mobile walking tour of downtown Chicago. Others stopped to discuss invasive species and ways they can help halt their spread.

But the biggest draw was our university Learning in Community (LINC) course poster, created by undergraduate students enrolled in our section last fall. These students focused on increasing awareness on campus about how pharmaceuticals contaminate our waterways. They also coordinated a take-back event for students and community members to properly dispose of their unwanted medication. The event was a big success, collecting 15 pounds of unused medicine for incineration in just six hours.

But the biggest draw was our university Learning in Community (LINC) course poster, created by undergraduate students enrolled in our section last fall. These students focused on increasing awareness on campus about how pharmaceuticals contaminate our waterways. They also coordinated a take-back event for students and community members to properly dispose of their unwanted medication. The event was a big success, collecting 15 pounds of unused medicine for incineration in just six hours.

For Kirsten and I, what was particularly exciting and unique about this symposium was our ability to connect with others working locally on related problems. For example, a Champaign community health center invited us to discuss pharmaceutical disposal with their patients. There was also a UIUC engineering student interested in the homemade filtration system our LINC students created with local high schoolers to show how some contaminants can slip through wastewater treatment processes. She is currently working to design and implement a water system and health program in a rural Honduran community and was looking for ways to engage with local residents.

Earlier this year, AP science students at Chicago’s Lane Tech College Prep traded in their textbooks for field equipment to study water quality in the North Branch of the Chicago River. The Hydrolab allows students to monitor water characteristics like dissolved oxygen, pH, and conductivity with sensors similar to those used by scientists at the EPA Great Lakes National Program Office. The teacher, Dianne Lebryk, borrowed the equipment through the Limno Loan program to help students better understand the connection between water quality and man-made landscapes.

Several students wrote in to share their experiences working with the Hydrolab. We wrap things up today with Gayin Au.

Under the circumstances of an extremely frosty cold weather, our environmental classmates were still very eager to head out and experience the Hydrolab. As soon as we reached the river by our school, we saw a lot of trash in the river. The water looked very dense and had a very dark green color.

Two people were responsible for holding the Hydrolab since it was quite heavy. The others stood back to watch. I was surprised that we were able to get results really quick; at first I thought it would take a lot of time to process the information.

Goose poop, which is high in nitrate, dissolves and mixes into the water and plants use this nitrogen to keep them nice and fertilized. However, the river is also greatly harming the living things in it. The water lacked oxygen, meaning it will be more difficult for living things in there to survive. It also might mean there aren’t enough plants underwater to keep the normal level of oxygen up. It was greatly contaminated, and fish and other organisms will be affected, making them act unusually.

The lab was really quick and useful. It showed us the oxygen level, how much algae is in there, how polluted the river is in general, and more. The river goes by so many things that can affect it. Human trash, fertilizer, and goose poop (common near our school thanks to large fields of grass) all affect the quality of water.

Several IISG staff members were in Grand Rapids, MI earlier this month to share some of our education resources and curricula during the Great Lakes Place-based Education Conference. For Allison Neubauer, the experience had an unexpected twist.

Stewardship and place-based education are nothing new to us educators at Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant. In fact, the IISG education team has been leading efforts in these initiatives throughout southern Lake Michigan communities for years. For this reason, going into the conference, I thought it was a great opportunity for us to share our models of stewardship and place-based education. I didn’t plan on gaining much insight into how and why these objectives were critical. Boy, was I wrong.

IISG undoubtedly has an arsenal of exemplary stewardship models, and a jam-packed room of eager educators at our Friday afternoon session was an indication of their desire to hear how we’ve extended learning beyond classrooms and into communities.

But as much as I enjoyed sharing our examples of student stewardship as a means of combatting invasive species, promoting proper disposal of unwanted medication, and teaching about benefits and risks of fish consumption, the best part of the conference was actually hearing others share their stories.

The opening keynote address by Kim Rowland, a middle school science teacher, detailed how her students have been able to use their surrounding environment in Grand Rapids as a resource for exploration and learning. What was most captivating and exciting to hear was how this time spent investigating the outdoors was a way to reach students that are not typically high academic achievers. Kim told us about a particular student who was always getting in trouble—not wanting to come to school, and certainly not excited about learning. Though she had not anticipated this, venturing out to the stream on school property transformed him into the most enthusiastic student of the group. In fact, this student was now so interested in collecting samples that he waded even further into the stream, thus giving Kim a very fitting title for her presentation: “Getting Your Feet Wet and Allowing Water to Flood Your Boots.”

This was a great way to kick-off the conference. It really impressed upon me that place-based education should not be considered a luxury, or something that only all-star teachers are doing. Every student—from urban to rural, high achieving to special needs—must be exposed to learning outside the classroom. School should not take place in isolation, between the same four walls everyday. There is immense value in connecting students with their communities and surrounding environments as a means to enhance learning and civic understanding.