February 21st, 2018 by IISG

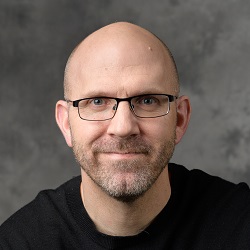

Tomas Höök has taken the lead as director of Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, managing program administration at Purdue University after the transition from University of Illinois. Höök, who has been with IISG since 2010, was previously the program’s associate director of research. He replaces Brian Miller, who served as IISG director for the past ten years.

“As director, I initially hope to help guide the program through the transition period as our administration moves from Illinois to Purdue and new staff members come on board, all while dealing with uncertain federal funding scenarios,” Höök said. “Eventually, I’d like to help our program develop new initiatives, partnerships and approaches to help inform and empower Illinois and Indiana communities.”

Höök holds an appointment as associate professor of fisheries and aquatic sciences in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources at Purdue University. He directs a Purdue research lab that investigates environmental questions at the interface between applied and basic ecology, focusing on fish and fisheries ecology in the Great Lakes.

“Purdue is thrilled that Dr. Tomas Hook will serve as the next director of Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant,” said Robert Wagner, head of Purdue’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources. “Tomas brings outstanding previous experience with IISG, as well as incredible expertise, to this leadership position. We are happy to once again serve as the lead institution for the next phase of Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant.”

Höök grew up in Sweden but completed high school in Alabama when his family moved to the United States and he now holds dual citizenship in both countries. He received his BS, MS and PhD from the University of Michigan. Prior to joining IISG and Purdue University, he worked at the Cooperative Institute for Limnology and Ecosystems Research (now known as CIGLR) and as a visiting scientist at Stockholm University in Sweden. Höök is also a former president of the International Association for Great Lakes Research.

“I enjoy working with IISG because I believe our program makes a real difference through applied research and engagement, thereby facilitating communities in Illinois and Indiana to improve quality of life and environmental conditions around Lake Michigan,” said Höök. “I also appreciate that IISG staff members are a dedicated, knowledgeable and fun bunch to work with.”

February 13th, 2018 by IISG

Brian Miller has been director of the Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant program for 10 years. He retired on February 1, 2018, as the program administration transitioned from the University of Illinois to Purdue University. Below is an interview from his final days with IISG.

What is your history with the IISG program?

I started back in 1994 as the extension program leader. The program began at the University of Illinois, and in 1994, it came to Purdue when the university asked for the opportunity to take a shot at running the administration. At that time, IISG was very small. There was no research program, the director, Phil Pope, was from Purdue’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources.

We got the research program reinstated, and in 1997 we achieved college status. In 2001, when Phil Pope retired, the two universities agreed that it would move to the University of Illinois to report to the vice chancellor of research.

Then, in 2007 I was hired as the director. When I was getting ready to retire, the same discussions came up that happened back in 1994 and in 2001. We’ve again decided to move the program to the partner university, so, we’ve really come full circle. The difference is that when it came to Purdue the first time, there were four people, one specialist, and a budget of about $300 thousand per year with no research. And nobody really knew who we were or what we did. It was hard to become a partner in a big place like Chicago. People in the universities didn’t know what to do with us, and people on the coast didn’t know what to do with us. It was just a small program.

Today, the program is coming over to Purdue with 18 specialists and more than 175 partners. I think the big thing that’s changed is that we no longer have to walk through the door and explain what we do, and we don’t have to try to convince people to work with us. In a lot of cases, it goes the other way, where we’re asked to help participate and solve problems. We’re seen as a program that can bring science and expertise to bear on tough community, state, and regional resource issues. And that really was the dream initially. So, I think that provides a pretty good platform for moving forward with the next administration.

What have been IISG’s greatest impacts during your time as director?

I think one of the things that we’re known for nationally is that we help local communities with planning, whether it’s watershed planning, land use planning, sustainable water planning, or thinking about planning for hazards and how to be resilient so we’re not more susceptible to flooding. We try to make sure that everything we do helps somebody make a decision—about management or policy or even personal decisions—that balances their goals with what’s best for the coast.

I’m pretty proud of the connection we’ve made between universities and communities. Researchers now have the ability to take their results and, instead of just depositing them somewhere like publications or the library, they can incorporate them into a decision support system that communities can use. Three great examples of that are GreatLakesMonitoring.org, Tipping Point Planner, and Great Lakes to Gulf.

Brian Miller, right, listens as Purdue University graduate student Valeria Mijares talks about research on comprehensive indicators of water quality. Seated from left are Sherry Martin, research associate, Michigan State University, Danielle Gerlach, Michigan Sea Grant intern, Mary Bohling, extension educator, and Dan Walker, IISG community planning extension specialist.

The last big project I got involved with was the Illinois Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy. That was one of the most challenging projects, but it was also the most rewarding. I was asked to help facilitate the process to develop and implement a nutrient loss reduction strategy in Illinois. The Illinois Water Resources Center and IISG really work together on this. I am proud of facilitating a policy workgroup, made up of a wide array of stakeholders that were able to come together and develop a solution. We had seven workgroups, and in two years we were able to publish the Illinois Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy.

Last August, we released our first biannual report that demonstrated big changes in land use practices and best management practices along with a scientific report that showed a reduction in the loss of nutrients in the state. It was really rewarding to see people coming together to solve problems, and willing to try and make sure they’re protecting the water and the environment we all share. That experience was kind of a capstone that brought together all of my experiences and knowledge during my time with Sea Grant.

What has it meant to you to be part of the Sea Grant network?

When I started in 1994, the very first meeting I met my peers at other Sea Grant institutions, we just all immediately became friends. Through my whole career, that feeling never changed. There were often national competitions for money or national research competitions where we could’ve easily become competitors and fought with each other, but we never did. In the Great Lakes, there’s been a long tradition of networking and partnering.

Something I really appreciate from the Sea Grant network is that we are all based at the core in university science. We start with the facts. We may have different ideas of how to get there, but we’re able to find a way to do it together for the greatest impact. Over the years, the focus has shifted from “How many pubs did you create?” to “So, what did it do? How was it used? Did the environment change because of what you did?” That was a very different way of thinking, and I think Sea Grant was one of the leading agencies and groups to embrace that.

One of the coolest things that I got involved with was creating the Sea Grant Academy. Up until the late ‘90s and early 2000s, there was nowhere to learn how to focus on impacts, to learn how to plan new programs, and to get the ethos of what a good extension or Sea Grant program should really be. And so, we decided to develop an academy. It’s been conducted every two years since then. After our third academy, 10 percent of all the program leaders were academy graduates. And I think that number is higher now.

Two of the cornerstones of academy training is how to design programs for impact and to learn how to report to Congress and your state legislators and communities with demonstrated impacts. And I think that’s just a philosophy that always gave purpose and meaning to me personally. That seems to be the philosophy that drives Sea Grant, and I think that’s what being part of that network has meant to me.

What will you miss most about being involved with IISG?

The people. The thing that has always been so special about Sea Grant is the people. There’s an old cliché and you hear it a lot: “We’re like family,” but it really is like that with IISG. There is always a cooperative spirit. We all work together. It doesn’t matter that we work in separate states. It doesn’t matter that we have different universities. It doesn’t matter that, in all other aspects, we would be competing for resources. But because we are part of Sea Grant, we work together, we get credit for working together, and we know that we’re stronger for doing that.

IISG staff members, Kristin TePas and Tomas Hook, and former IISG employee, Jarrod Doucette, reminiscing with Brian Miller at his retirement party.

We respect each other as colleagues and friends. I’ve appreciated that throughout my entire career. It’s added a lot of value to my memories, my career satisfaction, and everyone I’ve gotten to know has added to my perspective of how I view the world and how to operate in it. That’s something that I’ll really miss. You don’t get that in every career.

What are your plans after retiring?

I grew up in southern Indiana. Both my grandparents farmed. I was raised as a kid spending all my summers on the farm, and that’s where I got involved in wildlife and forestry and water resources. Then, I came to Purdue and got a degree and became a wildlife biologist. I worked in Connecticut as a wild turkey and small game biologist and then came back to Purdue to work as a wildlife extension specialist. I started to realize that just working on wildlife habitat wasn’t good enough–I realized that if we weren’t working with land use planning, we weren’t going to solve any problems.

Then Sea Grant really helped me broaden into water, fisheries, and coastal issues. So, I went from being a specialist to being a generalist really. But toward the end of my career, I also got involved in farming and nutrient issues. Now, as I retire, I’m going back to the farm that’s been in my family for 150 years, and it’s got a house on it that was built in 1905. I’ve added wetlands, and I have short grass prairie and tall grass prairie. I have mature woodlands, and I’ve planted bottom land hardwoods. And now, I have the chance to put a lot of what I’ve done and learned back into practice with my own hands again. In a lot of ways, it’s all kind of come full circle.

* This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

February 5th, 2018 by IISG

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. – Purdue University will administer the Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant College Program (IISG), previously managed by the University of Illinois, effective Feb. 1, 2018. New IISG director Tomas Höök, a fisheries biologist in Purdue’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, will lead the administration.

IISG research, outreach and education efforts bring the latest science to southern Lake Michigan residents and decision makers and empower them to secure a healthy environment and economy.

The program has been a leader in the region on aquatic invasive species control, pollution prevention and Great Lakes literacy, and has developed decision tools that help communities grow while protecting natural resources. Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant supports more than 50 permanent medicine collection programs in the Great Lakes region, has helped the Indiana aquaculture industry grow fivefold and provides resources for municipalities to plan for future water supplies.

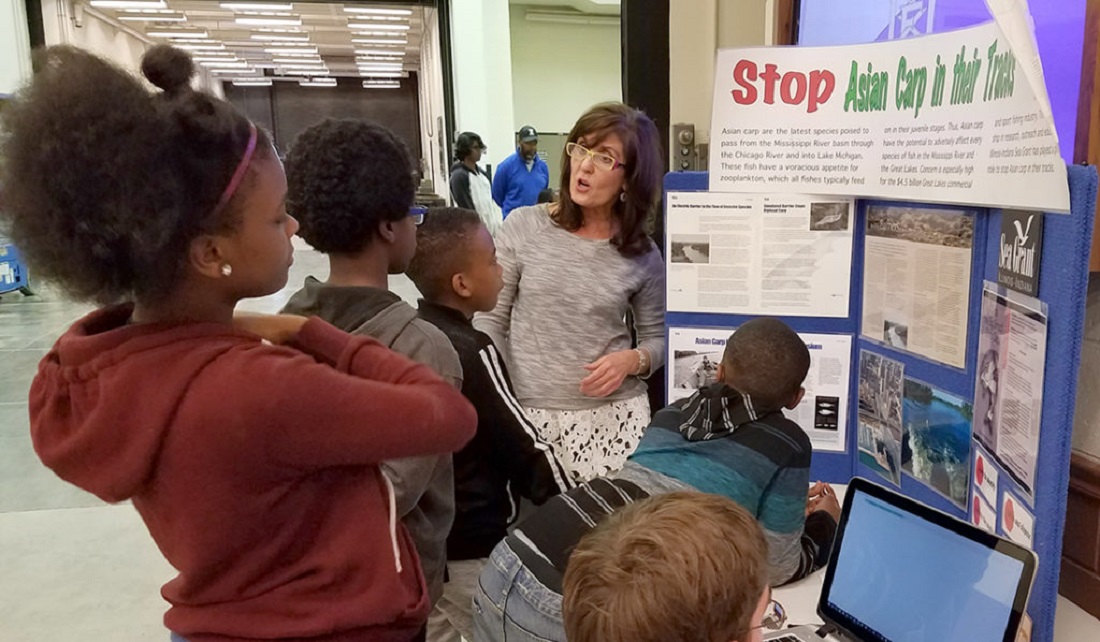

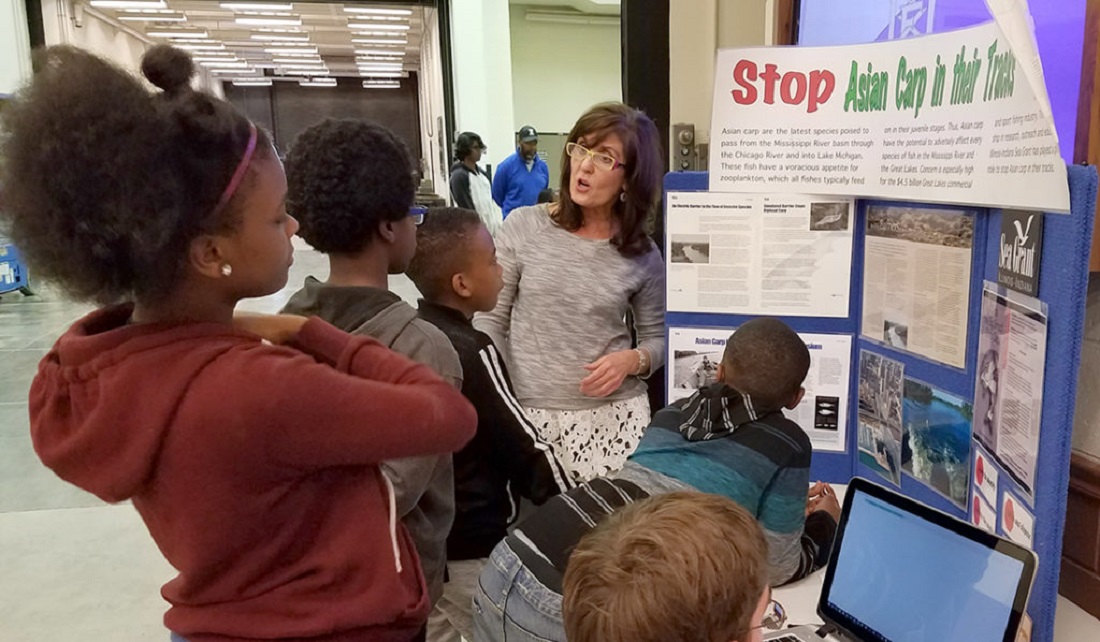

Terri Hallesy, IISG education coordinator, engages elementary students at the University of Illinois’ Brady STEM Academy about the threat of Asian carp to the Great Lakes.

IISG is funded through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Purdue University and the University of Illinois.

Tomas Höök, Director

“While Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant has recently been administered by the University of Illinois, it has always been a truly bi-state program,” says Höök, who has served as IISG’s associate director for research since 2010. “For the past 16 years, the program has greatly benefitted from IISG leadership at Illinois, especially Brian Miller and Lisa Merrifield. With program administration moving to Purdue, IISG will continue to work to empower Lake Michigan communities in both Illinois and Indiana through applied discovery and information dissemination.”

Purdue University and the University of Illinois have worked closely to oversee IISG since 1982, periodically transferring the program directorship. Over its 36 years, the program has maintained an administrative presence at both universities.

“When I started my career with Sea Grant in 1994, we were going through an administrative transition similar to the one happening right now,” says Brian Miller, who has been program director for 11 years and is now retiring. “What we have accomplished since that time provides a wonderful platform for even greater growth in the future.”

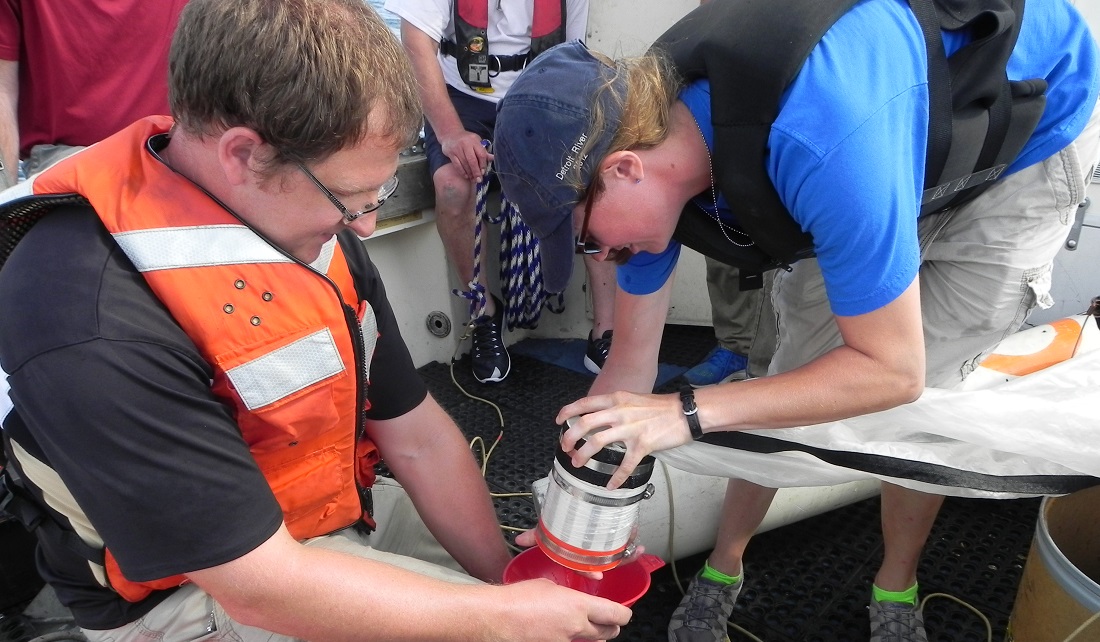

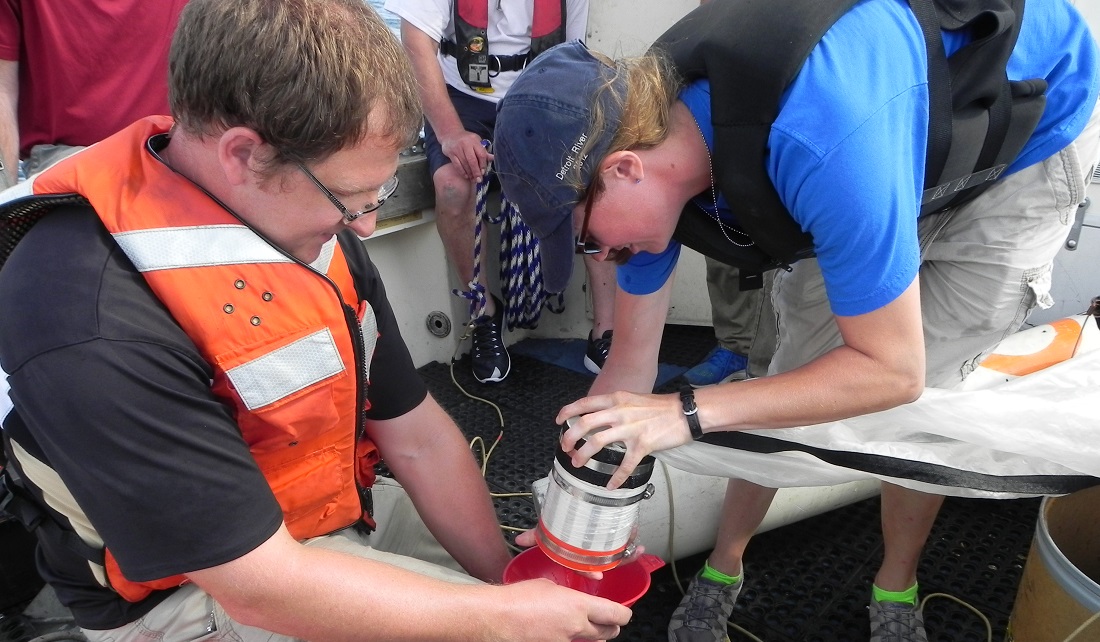

IISG Aquatic Ecologist Jay Beugly helps Purdue University student Margaret Hutton sample Lake Michigan water near Wilmette, Illinois.

IISG is part of the National Sea Grant College program, established in 1966 to protect and preserve America’s coastline and water resources to create a sustainable economy and environment. The network consists of a partnership between NOAA and 33 university-based programs in every coastal and Great Lakes state.

December 20th, 2017 by IISG

My name is Kate Gardiner and I recently joined the Illinois Water Resources Center (IWRC) as a part-time communications coordinator. Prior to starting at IWRC, I interned at the Institute for Sustainability, Energy, and Environment and earned my B.S. from the University of Illinois in environmental sustainability.

Since sustainability can be so widely applied, the University of Illinois now incorporates lessons in sustainability into a multitude of courses in different fields spanning from business to architecture. Recently, I had the opportunity to join Eliana Brown, outreach specialist and rain garden expert with IWRC, to visit a landscape architecture class and provide feedback for the students’ final design review.

One of the key objectives of Landscape Architecture (LA) 452, led by Katherine Kraszewska, is to teach students to identify and incorporate native plant species when envisioning a new landscape. This is a win-win, as the native plants attract pollinators and, when used in rain gardens, can improve downstream water quality.

For their designs, students were instructed to increase connectivity between pollinator pockets and consider stormwater management. Pollinator pockets are spaces with native plants, serving as an oasis for butterflies, bees, hummingbirds, and other pollinators traveling through the area. Pollinator pockets are scattered throughout the U of I campus, including the Facilities & Services’ low mow zones and the Master Gardener Idea Garden.

We spoke with several students about their designs, here are some of our favorites!

Landscape architecture senior Layne Knoche designed a sunken courtyard by the Allen Hall dormitory. His plan included a small grass lawn, native plantings that attract pollinators, and a patio for students to sit and enjoy nature. He chose his plantings based on seasonality, moisture tolerance, plant heights, and what pollinators they attract so that the garden could be beautiful all year round as well as attract different species.

Maria Esker, also a landscape architecture senior, designed an interactive campus rain garden. It included a path through the garden, large boulders along the path for sitting, and a wide range of native plantings for people to enjoy year round. Her rain garden would catch excess runoff from the adjacent parking lot and be a relief for pollinators traveling through campus.

Eliana shared with the students that they did a great job integrating concepts they learned in the rainscaping course into their final designs. This wasn’t the first time she visited the class—Eliana previously shared her expertise in a stormwater rainscaping guest lecture (along with Extension Educator Jason Haupt).

These bright students all had innovative and sustainably-inspired designs, greatly due to the teachings and encouragement from their professor as well as their own creativity. While reviewing their designs, we learned that many of the students in the class are graduating this year. As they move on from the university and start their careers, I wish them luck and hope they take what they’ve learned in LA 452 with them and apply it to their future designs.

Top photo, left to right: Terri Hallesy, Maria Esker, Eliana Brown, Katrina Widholm

Bottom photo, left to right: Katherine Kraszewska, Eliana Brown, Terri Hallesy, Katrina Widholm, and Kate Gardiner

November 27th, 2017 by IISG

Legacy pollutants—chemical contaminants left behind by industry from decades ago and prior to modern pollution laws—remain a burden in some Great Lakes communities. In fact, the U.S. side of the Great Lakes have 27 Areas of Concern (AOC) that are still considered impaired due to risks to human health, pollution, habitat loss, degradation and other issues.

“For the first time, we have a program and funding specifically dedicated to addressing the most pervasive environmental problem facing the AOCs,” said Matt Doss, policy director for the Great Lakes Commission. “Not only has the Legacy Act lead to actual cleanups of contaminated sediments—generating real, on-the-ground environmental improvements—it revitalized the entire AOC program by demonstrating that real progress was possible.”

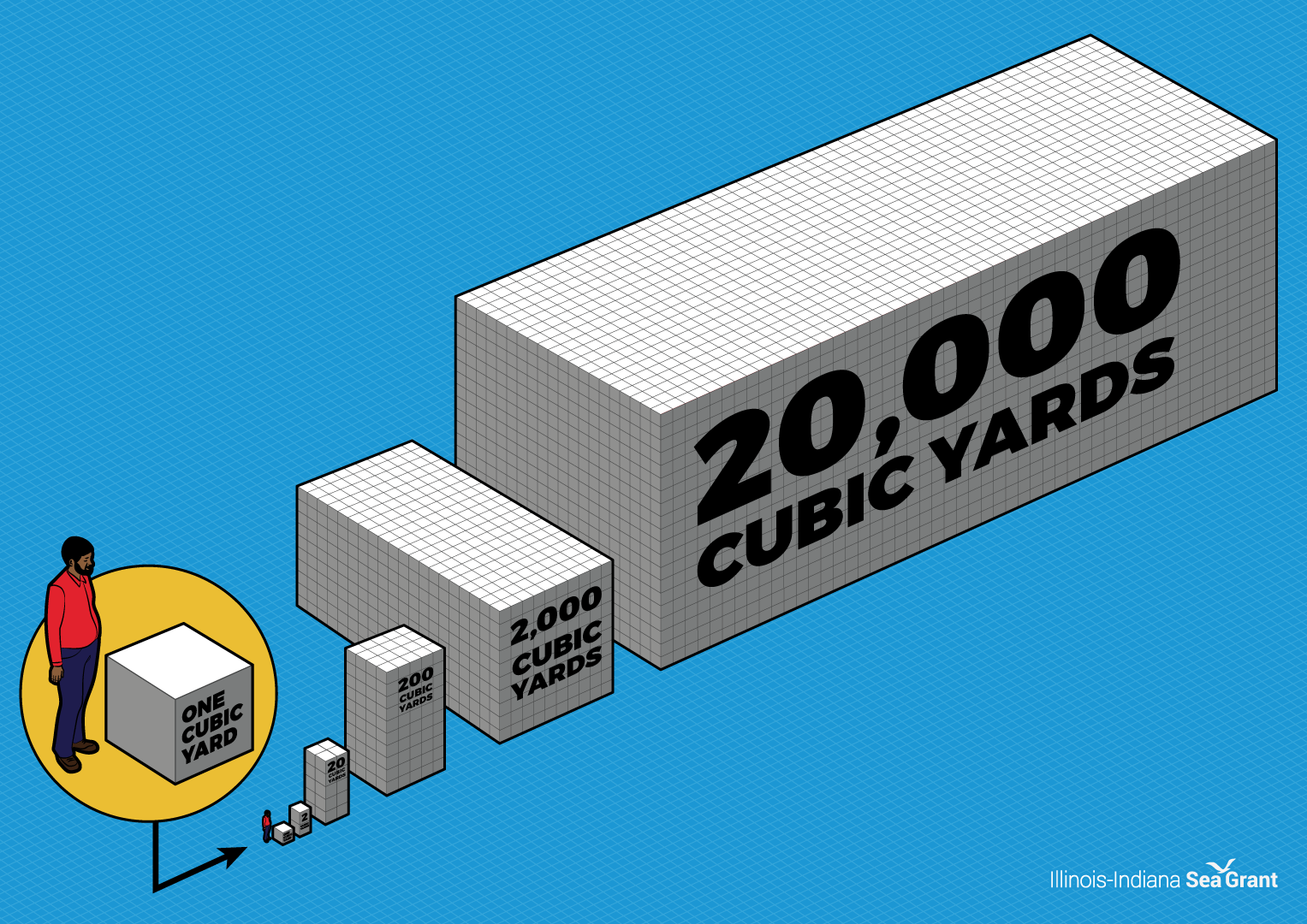

Over multiple projects, nearly 1 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment in the Buffalo River have been cleaned up through the Great Lakes Legacy Act.

The GLLA program is administered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Great Lakes National Program Office in Chicago, Illinois. GLLA uses a unique funding strategy that combines voluntary support from states, businesses, and non-governmental organizations, and the federal government through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant assesses outreach needs and engages stakeholders at the community level where GLLA sediment cleanups take place.

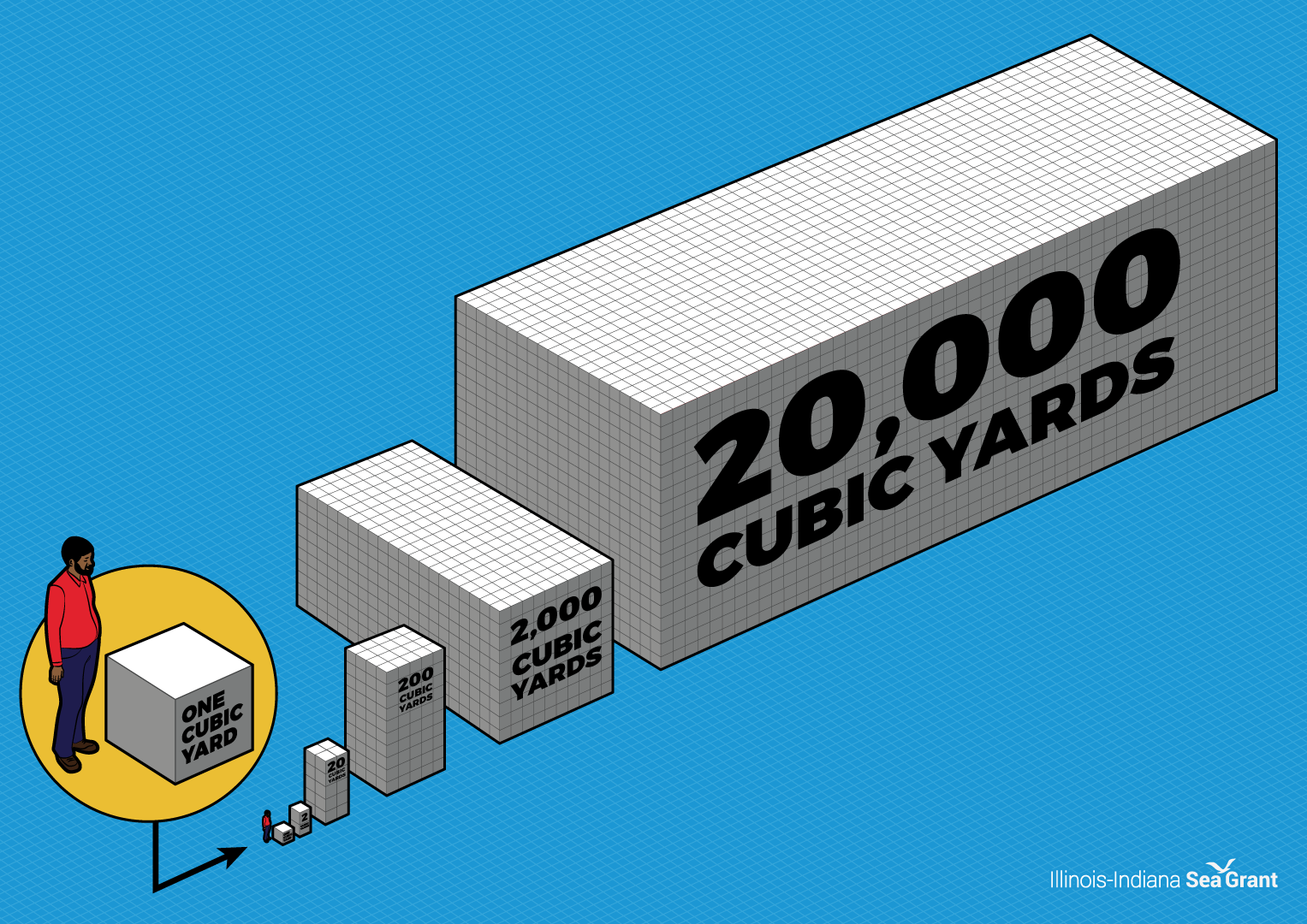

Sediment cleanups come in many sizes. The largest GLLA completed project dredged and capped one million cubic yards of contaminated sediment from the East Branch of the Grand Calumet River in northwest Indiana.

“Together, the State Natural Resource Trustees, Federal Natural Resource Trustees and EPA have spent over $180 million on sediment remediation projects in the Grand Calumet River, supporting a heathier fish community and attracting a robust migratory bird population,” said Bruno Pigott, Commissioner of the Indiana Department of Environmental Management.

To put dredge volumes in perspective, consider how the size of a single cubic yard compares to the average height of a man.

Much has been accomplished in the program’s first 15 years. Under GLLA, 21 projects are complete in six out of eight Great Lakes states, and more are in the planning stage. Through federal support and local funds, over $588 million has been spent to investigate sediment contamination, design cleanups, and implement solutions to pollution in AOCs.

“The Legacy Act is now among the most successful cleanup programs in the region and a cornerstone of the AOC program,” said Doss.

For the most comprehensive web coverage of sediment cleanups under the Great Lakes Legacy Act, visit www.greatlakesmud.org or follow Great Lakes Mud on Facebook.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

August 31st, 2017 by IISG

Too much of a good thing wore out the old medicine take-back box at the Urbana Police Department, so it recently received an upgrade.

“People come in here all the time and fill this thing up,” said Lieutenant Robert Fitzgerald. “The old one would fill up twice a week. It would just get packed.”

Since the department installed the box in 2013 as part of Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant and University of Illinois Extension’s medicine take-back program, it’s only grown in popularity. This box’s new style still resembles a mailbox, but a new locking feature prevents people from forcing pharmaceuticals into an already full box. Nobody will walk off with this one either. It’s bolted to the ground.

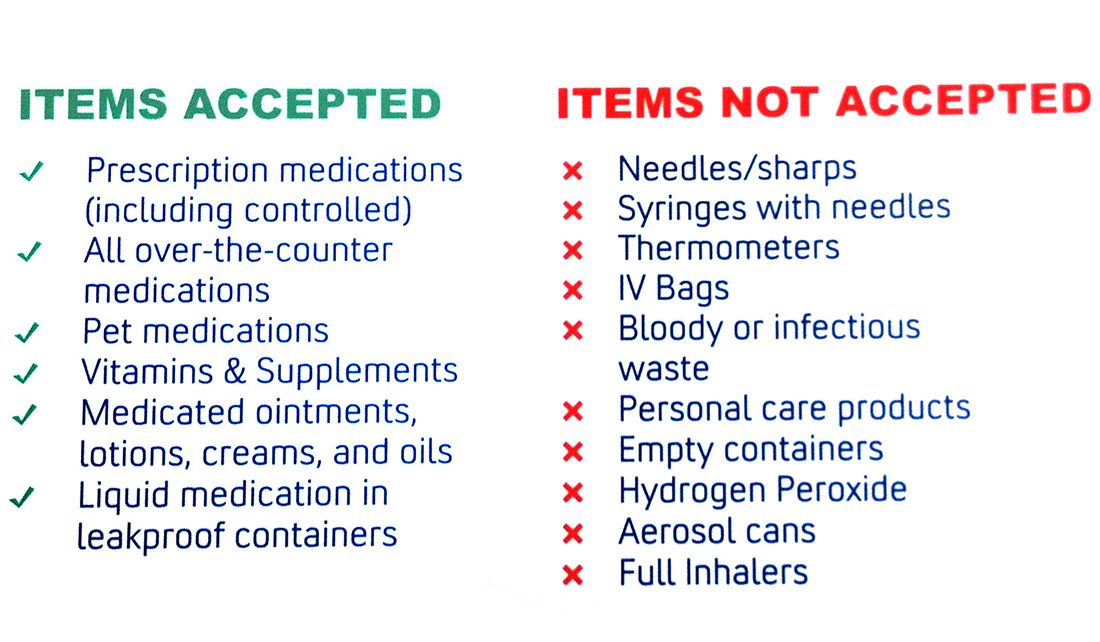

Medicine take-back programs help prevent these chemicals from being flushed or thrown in the trash, potentially contaminating local waterways. Taking in unwanted medicines is a public safety issue too.

“If we can take it here in this box, it means they’re not in somebody’s grasp at home—toddlers take anything they can grab,” said Amy Anderson, Urbana animal control officer/community liaison, who manages the box.

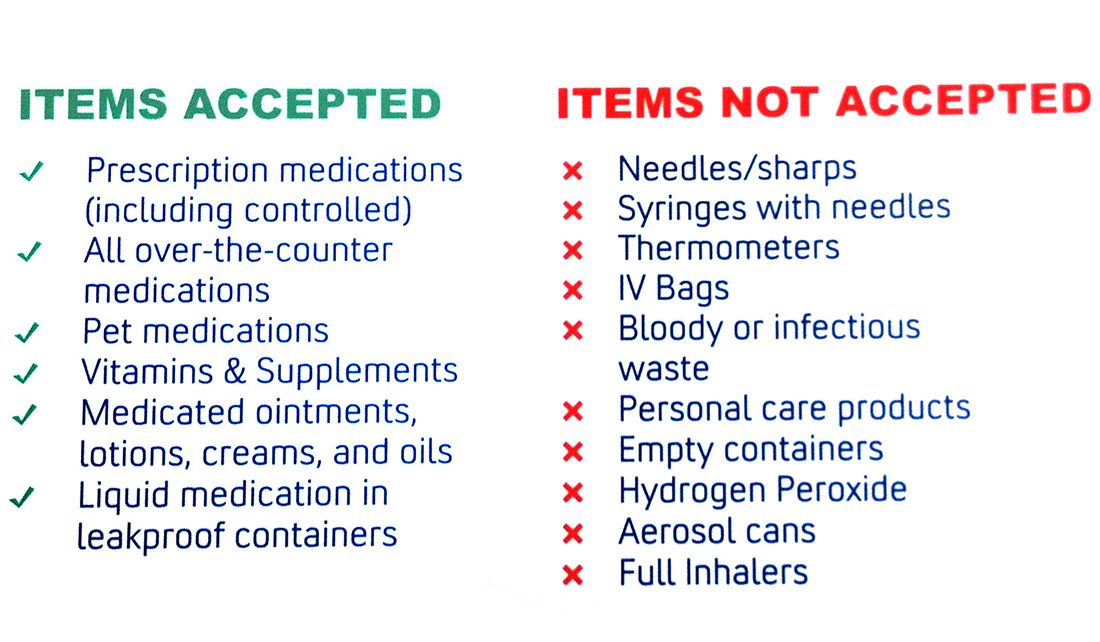

The police department, along with more than 50 locations in four states—including one in Champaign and one at the university—are designated to accept prescription and over-the-counter medicines, including veterinary pharmaceuticals, but not illicit drugs, syringes, needles or thermometers. IISG provides each location with the drug collection box and works with community partners to ensure the program’s success. All collected drugs are incinerated—the environmentally preferred disposal method.

The Champaign and Urbana medicine take-back programs started in 2013 and have collected more than 13,000 pounds of medicine. The IISG take-back program as a whole, which was established in 2007, has collected more than 58 tons. In addition, Sea Grant has helped collect over 30 tons just from helping out in single-day events throughout the Great Lakes region.

Amy Anderson, Urbana animal control officer/community liaison, (left) and Lieutenant Robert Fitzgerald pose with the new medicine take-back box in the lobby of the Urbana Police Department.

“The partnership we have with the Urbana Police Department, Champaign Police Department, and University of Illinois Police Department is so valuable,” said Sarah Zack, IISG pollution prevention extension specialist. “They do a great public service by operating this take-back program, and I hope that people can take advantage of the convenient drop-off locations in the C-U area.”

Be sure to visit unwantedmeds.org to find your local take-back location.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

July 19th, 2017 by IISG

A goldmine of recreational fishing data is now available in one place thanks to researchers and state government officials in Illinois and Indiana.

The website, Angler Archive, www.anglerarchive.org, is the brainchild of Mitchell Zischke, IISG research and extension fishery specialist at who saw the need for having the information more easily accessible when he was doing his own research.

The site currently contains over 50,000 records gathered between 1986 to 2013 by the Illinois Natural History Survey (INHS) and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources (Indiana DNR) in southern Lake Michigan during their seasonal “creel surveys.” Indiana not only surveys the lake but also nearby streams. Zischke will be updating the website as more data becomes available.

Creel surveys are conducted by state officials who interview the anglers while they’re fishing or at the end of their trip. The questions focus on how many fish and what species they caught; how much time they spent fishing; and where they caught the fish.

The website mirrors the creel surveys, but allows users to customize how and what data they want to see. They can use the drop-down menus to display and compare data by angler type, month, and species as well as generate and export the informaiton as a graph.

“In fact, I’m working on a project right now, analyzing data from the 80s and the 90s,” Zischke said. ”I’m finding there seems to be a relationship between the decline in yellow perch and the decline in the number of people fishing and the amount of time they spent fishing. Really, it’s just the beginning of diving into all this data.”

Researchers in both states who head up the creel surveys are looking forward to being able to share the data easily.

“I think it’s great. The more of our info that we collect that the public can see, the better,” said Ben Dickinson, Indiana DNR assistant Lake Michigan fisheries biologist.

“We try to go around to different fishing clubs and stakeholders and present this info, and so it’s nice to have a tool to point people to.”

Anglers frequently ask Charles Roswell, aquatic ecology assistant research scientist at INHS, who assisted in providing the data from the Illinois side, how the data from the surveys are going to be used.

“We have a short write-up on our website, describing how fisheries managers use the data, but I always thought it would be nice to have somewhere to direct people to look at what came out of the surveys, what data were actually collected, and what the data showed,” Roswell said. “This is something I always thought would be useful.”

This information spanning over 31 years will no doubt be useful and more easily accessible to researchers, fisheries managers, and curious anglers. For Zischke the data is already yielding some insights.

“It’s good to be able to look at these data now in a time series, as opposed to having to read a report every year. It highlights some interesting trends in fishing effort and in catch of some species, Zischke said.

“Now we’re in the process of exploring what may have caused some of these trends these through time.”

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

June 26th, 2017 by IISG

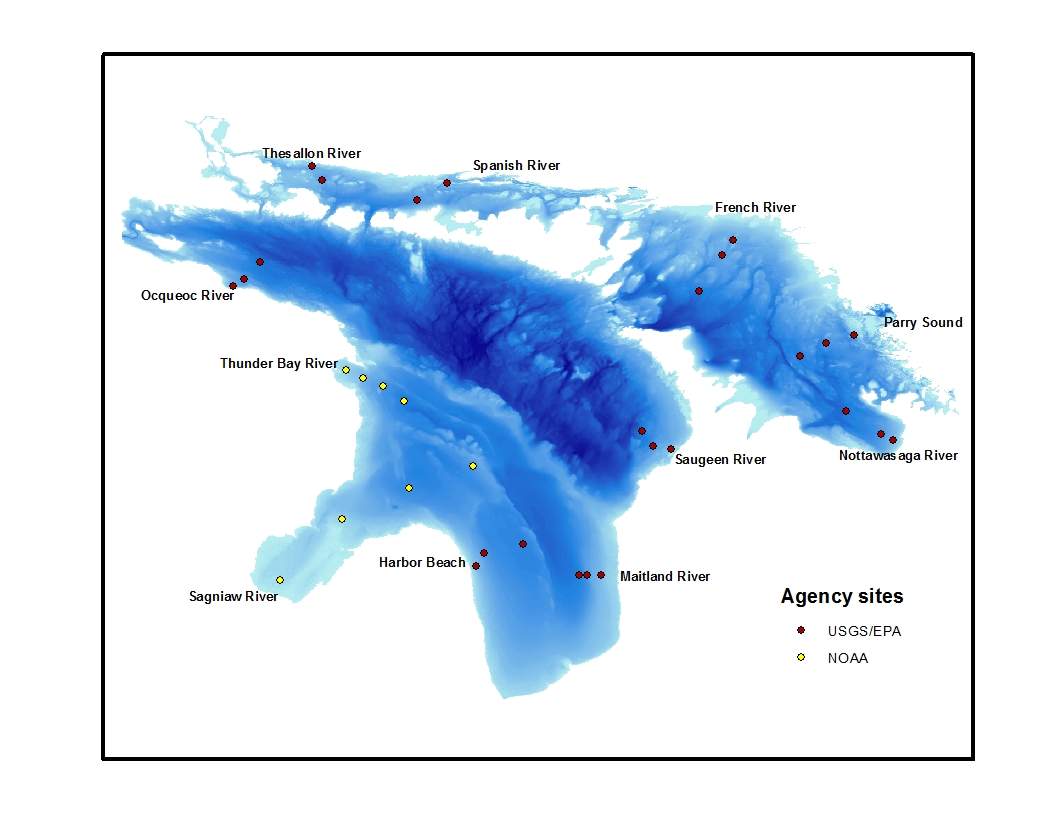

I’m aboard a 180-foot research vessel traversing Lake Huron; the ship is the U.S. EPA R/V Lake Guardian, and the goal is to take the pulse of this gaping freshwater entity. Every year the Cooperative Science and Monitoring Initiative (CSMI) comprehensively surveys one of the five Great Lakes. As a result, it’s been five years since we’ve taken a long look at Lake Huron.

Those working on this particular six-day research cruise vary from marine technicians who live on the ship for the whole sampling season, to scientists from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) onboard for the week to collect data and bring it back to their labs.

Left: A larval fish seen under a microscope. Right: The trawl net used to sample larval fish being pulled in over the sunrise.

And me?

I’m here with IISG as the Great Lakes communication and outreach intern, helping out with the sampling and observing so that when I’m back on land, I can use this experience to enhance my translations of scientific studies from the 2015 CSMI survey of Lake Michigan to engaging, accessible outreach materials for policy makers, fisheries managers, and the general public.

Clark working on the fantail.

I am on the 4 a.m. to 4 p.m. shift of this around-the-clock undertaking. At 3:30 a.m., I’ve got to hastily get up and shuffle down the hall to relieve the night shift on the back deck. I pull on my rain boots, life jacket, and hardhat, then grab a clipboard to record the samples as they come in. There are six sampling sites to complete on this cruise, and each composes a “transect,” a narrow section of water which runs perpendicular to the shoreline, providing an offshore, mid-shore, and nearshore snapshot.

Each station has a sampling agenda. If a station is reached at night, this protocol begins by sampling benthic, shrimp-like animals known as Mysis under red light. If the sun has already risen, we use an extremely large and well-outfitted CTD—an instrument that measures conductivity, temperature, and depth as it is deployed through the water column.

Next up is the zooplankton sampling, followed by two ichthyoplankton tows to sample larval fishes—the early stage in a fish’s life history where they are mere millimeters in length, floating about eating the zooplankton we sampled just prior. The larval fish collected are separated from the various bycatch of flotsam and examined back at USGS headquarters for a variety of parameters including species, length, and age.

The age data, collected by examining growth increments on the larvae’s minute otoliths (inner ear bones), is reported in days old. I find them enormously cute, in an E.T.-without-legs kind of a way.

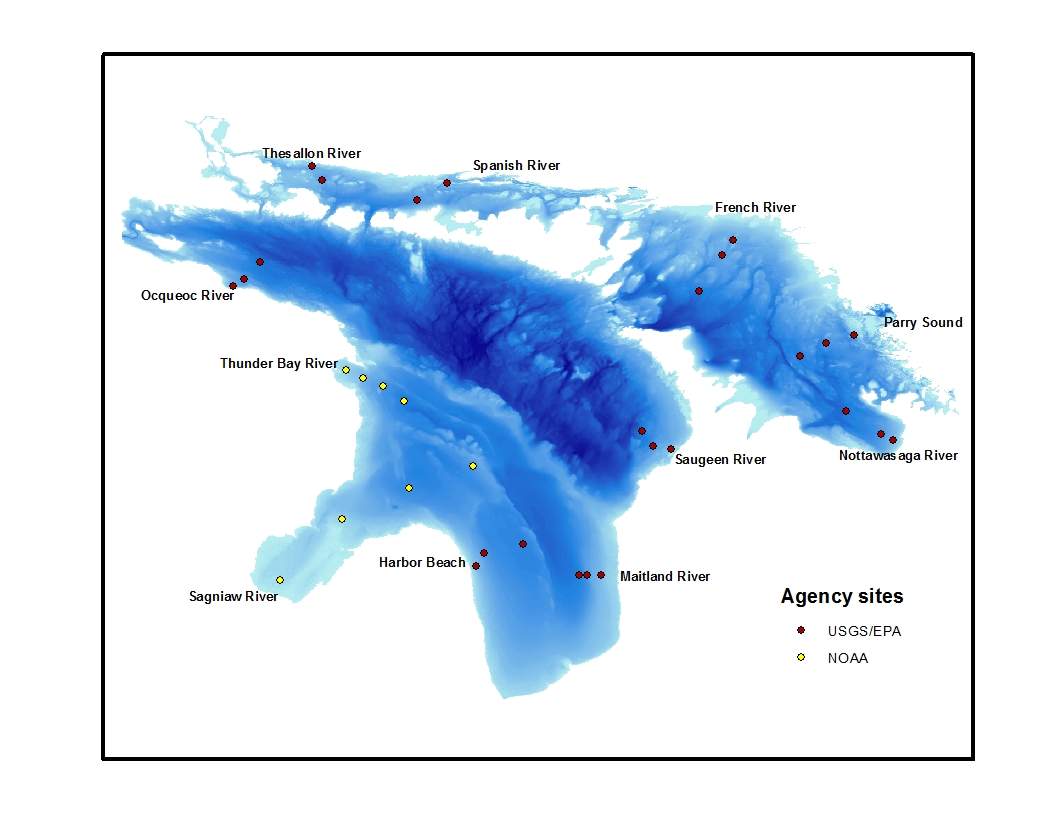

Map of the CSMI survey stations in Lake Huron. During this cruise Harbor Beach, Maitland River, Saugeen River, Nottawasaga River, Parry Sound, and French River transects were sampled, in that order.

After each of the three stations have been surveyed, a large sampling instrument called the Triaxus is towed back along the entire transect to gather information across the full survey area. Depending on the length of the transect, this can take a while.

I have found this a great time to hit the galley and grab a second or third breakfast, depending on the day. After all, by 9 a.m. I’ve been awake for a good five to six hours and there’s more sampling to do.

We then lower the Rosette, a big water sample collector, to measure the amount of chlorophyll in the water. We also put nets down six different times to collect zooplankton. We then used a big net to collect larval fish out the side or behind at different depths throughout the water column. We also towed the Triaxus for a few hours. We head to the next transect and do it all over again.

And—if we’re lucky—in exchange for all our hard work, the next time I crawl out of my bunk at 3 in the morning I get to witness a scene like this one:

Emily Clark is working with Paris Collingsworth and Kristin TePas as a summer intern with IISG where she is creating outreach materials for the results of the 2015 Lake Michigan CSMI field year. Clark is a student at College of Charleston in South Carolina studying biology, environmental studies, and studio art.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

June 22nd, 2017 by IISG

Unfortunately in the United States we pollute at a rate much faster than we can put control measures in place. New chemicals and substances are continually being developed and used to enhance our industrial processes and products. A drawback to this advancement is that in some cases, when a chemical so novel, we have difficulty understanding the full effects it’s having on the environment or public health. This is what researchers are looking into when they study emerging contaminants.

As part of the IISG pollution prevention team led by Sarah Zack, I attended the Emerging Contaminants in the Aquatic Environment Conference (ECAEC), organized by the Illinois Sustainable Technology Center and IISG. The conference was a two-day crash course on the newest pollutants causing concern for the health of our waterways. Nearly 100 people attended to listen to four invited speakers, 27 contributed talks, and view 18 posters.

While last year’s conference zeroed in on contamination from pharmaceuticals and personal care products, this year we heard from researchers studying a wide variety of contaminants—from harsh-sounding chemicals used for things like flame retardants and stain repellents, to everyday items winding up as litter and microplastic on our beaches.

I found it reassuring to hear from researchers who are working so diligently to understand how these contaminants are getting into our water, how they move through the ecosystem, and their effects on not only the tiniest organisms in the environment, like microscopic plankton but all the way up to humans as well.

One of the four keynote speakers, Barbara Mahler from the U.S. Geological Survey, presented her research on coal-tar-based pavement sealcoat that is sprayed or painted on top of many asphalt parking lots, driveways, and playgrounds. Mahler found that coal-tar sealcoat, and particularly the dust that results from its wear and tear, is a major source of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) contamination. Many PAHs are known to cause cancer, mutations, and birth defects in addition to being acutely toxic to aquatic life. Her work has informed policy in Austin, Texas where she conducted her research, as well as in other states and cities across the country.

Another keynote and familiar face for Illinois-Indiana Sea Granters, Tim Hoellein discussed several projects he’s working on relating to anthropogenic litter—trash that is making its way from people onto our beaches, in our rivers, and ending up in our Great Lakes.

And it’s not just the chemists and biologists who are toiling away on this complex, moving-target-of-an-issue. Having been to my share of scientific conferences, I was impressed at the variety of disciplines represented at ECAEC. Social scientists, educators, and even an attorney (yet another captivating keynote speaker, Stephanie Showalter Otts) also weighed in on the conversation of how to tackle the problem of emerging contaminants.

For me, it was especially cool to hear scientists in the room call out the necessity of working across disciplines and involving social scientists to further the reach of their research. It’s clear that the road ahead will not be easy, but I walked away from this conference feeling encouraged that there are brilliant, innovative people who are working to address these challenges from many angles.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.