December 20th, 2017 by IISG

My name is Kate Gardiner and I recently joined the Illinois Water Resources Center (IWRC) as a part-time communications coordinator. Prior to starting at IWRC, I interned at the Institute for Sustainability, Energy, and Environment and earned my B.S. from the University of Illinois in environmental sustainability.

Since sustainability can be so widely applied, the University of Illinois now incorporates lessons in sustainability into a multitude of courses in different fields spanning from business to architecture. Recently, I had the opportunity to join Eliana Brown, outreach specialist and rain garden expert with IWRC, to visit a landscape architecture class and provide feedback for the students’ final design review.

One of the key objectives of Landscape Architecture (LA) 452, led by Katherine Kraszewska, is to teach students to identify and incorporate native plant species when envisioning a new landscape. This is a win-win, as the native plants attract pollinators and, when used in rain gardens, can improve downstream water quality.

For their designs, students were instructed to increase connectivity between pollinator pockets and consider stormwater management. Pollinator pockets are spaces with native plants, serving as an oasis for butterflies, bees, hummingbirds, and other pollinators traveling through the area. Pollinator pockets are scattered throughout the U of I campus, including the Facilities & Services’ low mow zones and the Master Gardener Idea Garden.

We spoke with several students about their designs, here are some of our favorites!

Landscape architecture senior Layne Knoche designed a sunken courtyard by the Allen Hall dormitory. His plan included a small grass lawn, native plantings that attract pollinators, and a patio for students to sit and enjoy nature. He chose his plantings based on seasonality, moisture tolerance, plant heights, and what pollinators they attract so that the garden could be beautiful all year round as well as attract different species.

Maria Esker, also a landscape architecture senior, designed an interactive campus rain garden. It included a path through the garden, large boulders along the path for sitting, and a wide range of native plantings for people to enjoy year round. Her rain garden would catch excess runoff from the adjacent parking lot and be a relief for pollinators traveling through campus.

Eliana shared with the students that they did a great job integrating concepts they learned in the rainscaping course into their final designs. This wasn’t the first time she visited the class—Eliana previously shared her expertise in a stormwater rainscaping guest lecture (along with Extension Educator Jason Haupt).

These bright students all had innovative and sustainably-inspired designs, greatly due to the teachings and encouragement from their professor as well as their own creativity. While reviewing their designs, we learned that many of the students in the class are graduating this year. As they move on from the university and start their careers, I wish them luck and hope they take what they’ve learned in LA 452 with them and apply it to their future designs.

Top photo, left to right: Terri Hallesy, Maria Esker, Eliana Brown, Katrina Widholm

Bottom photo, left to right: Katherine Kraszewska, Eliana Brown, Terri Hallesy, Katrina Widholm, and Kate Gardiner

November 27th, 2017 by IISG

Legacy pollutants—chemical contaminants left behind by industry from decades ago and prior to modern pollution laws—remain a burden in some Great Lakes communities. In fact, the U.S. side of the Great Lakes have 27 Areas of Concern (AOC) that are still considered impaired due to risks to human health, pollution, habitat loss, degradation and other issues.

“For the first time, we have a program and funding specifically dedicated to addressing the most pervasive environmental problem facing the AOCs,” said Matt Doss, policy director for the Great Lakes Commission. “Not only has the Legacy Act lead to actual cleanups of contaminated sediments—generating real, on-the-ground environmental improvements—it revitalized the entire AOC program by demonstrating that real progress was possible.”

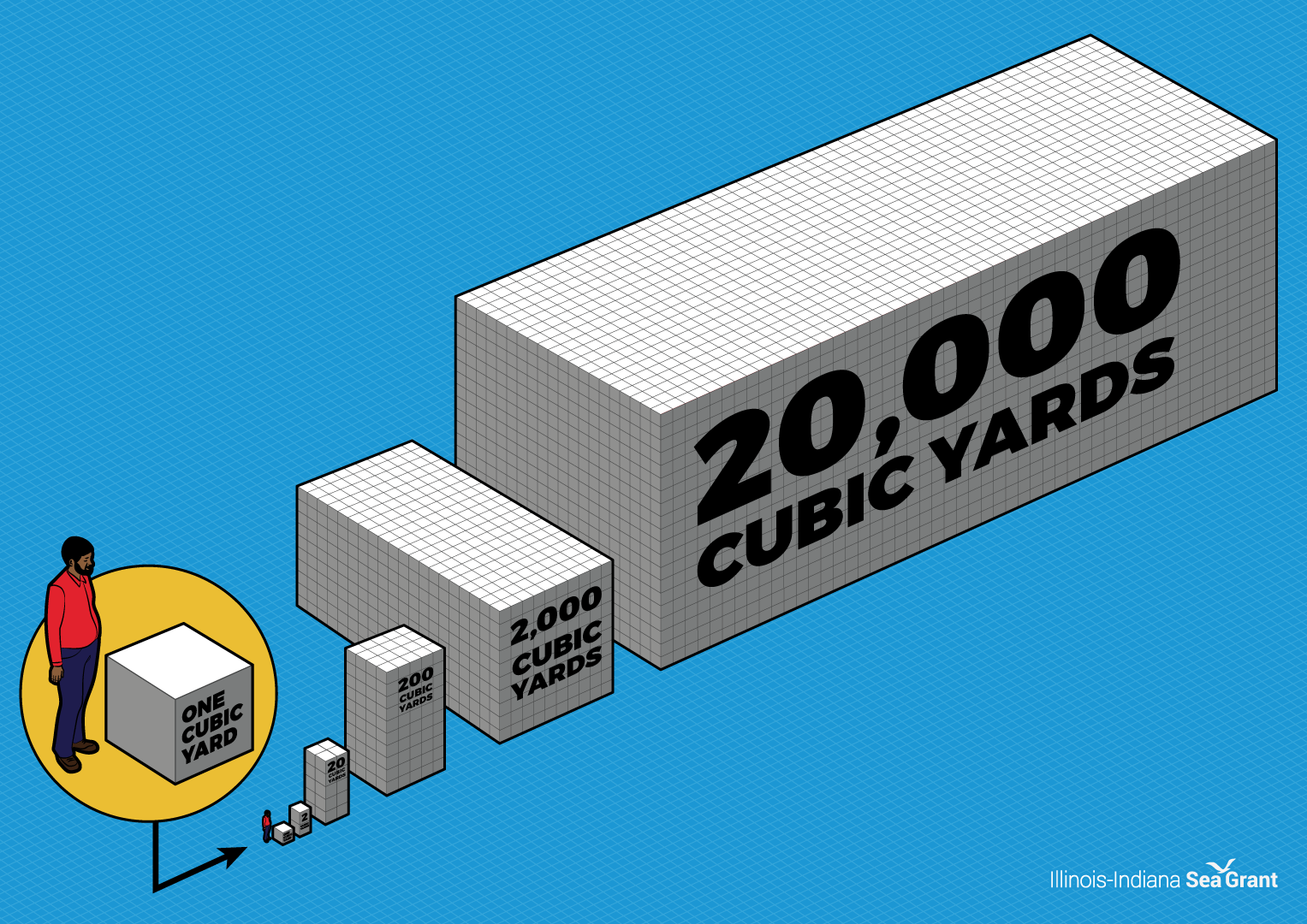

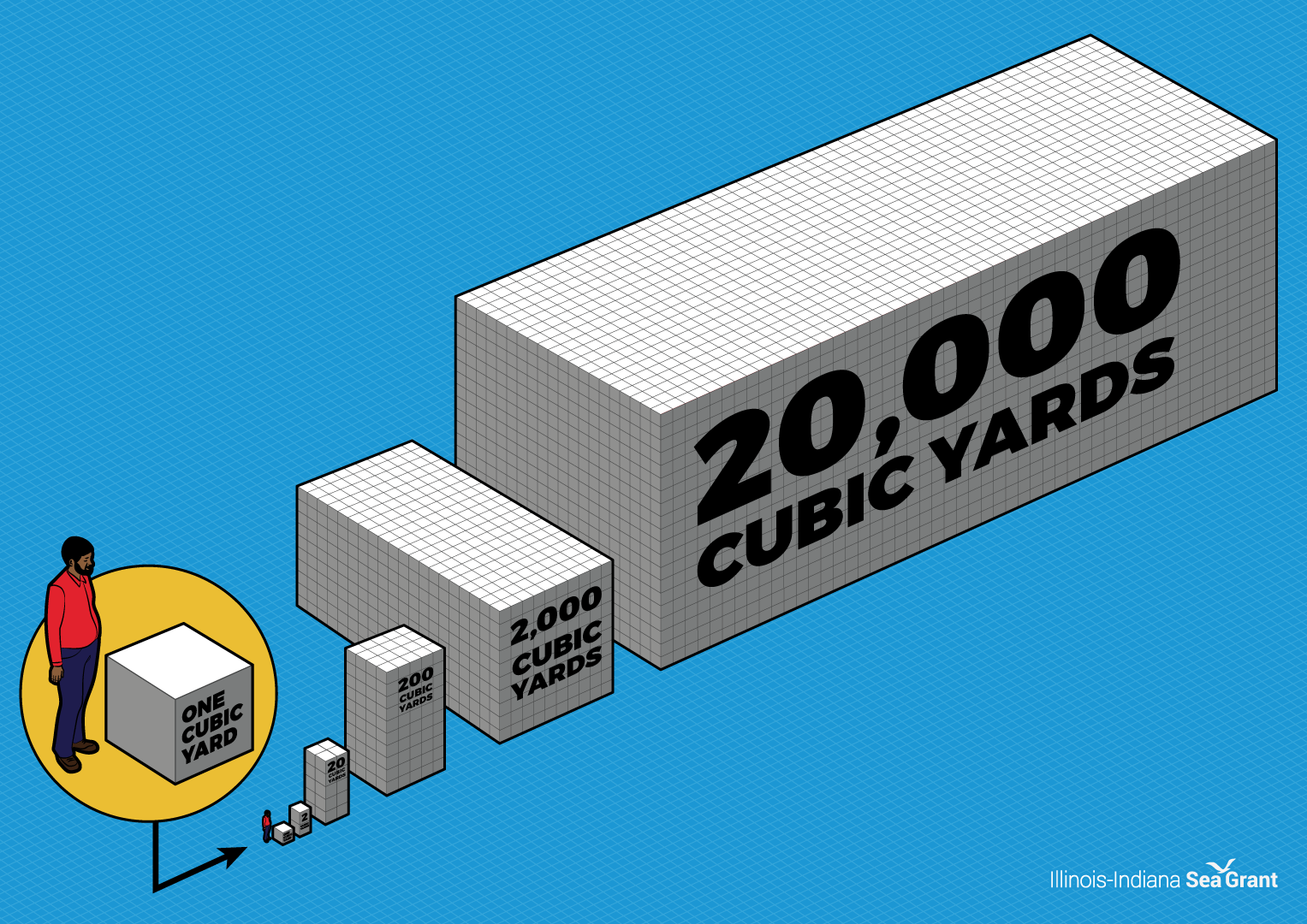

Over multiple projects, nearly 1 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment in the Buffalo River have been cleaned up through the Great Lakes Legacy Act.

The GLLA program is administered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Great Lakes National Program Office in Chicago, Illinois. GLLA uses a unique funding strategy that combines voluntary support from states, businesses, and non-governmental organizations, and the federal government through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant assesses outreach needs and engages stakeholders at the community level where GLLA sediment cleanups take place.

Sediment cleanups come in many sizes. The largest GLLA completed project dredged and capped one million cubic yards of contaminated sediment from the East Branch of the Grand Calumet River in northwest Indiana.

“Together, the State Natural Resource Trustees, Federal Natural Resource Trustees and EPA have spent over $180 million on sediment remediation projects in the Grand Calumet River, supporting a heathier fish community and attracting a robust migratory bird population,” said Bruno Pigott, Commissioner of the Indiana Department of Environmental Management.

To put dredge volumes in perspective, consider how the size of a single cubic yard compares to the average height of a man.

Much has been accomplished in the program’s first 15 years. Under GLLA, 21 projects are complete in six out of eight Great Lakes states, and more are in the planning stage. Through federal support and local funds, over $588 million has been spent to investigate sediment contamination, design cleanups, and implement solutions to pollution in AOCs.

“The Legacy Act is now among the most successful cleanup programs in the region and a cornerstone of the AOC program,” said Doss.

For the most comprehensive web coverage of sediment cleanups under the Great Lakes Legacy Act, visit www.greatlakesmud.org or follow Great Lakes Mud on Facebook.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

August 31st, 2017 by IISG

Too much of a good thing wore out the old medicine take-back box at the Urbana Police Department, so it recently received an upgrade.

“People come in here all the time and fill this thing up,” said Lieutenant Robert Fitzgerald. “The old one would fill up twice a week. It would just get packed.”

Since the department installed the box in 2013 as part of Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant and University of Illinois Extension’s medicine take-back program, it’s only grown in popularity. This box’s new style still resembles a mailbox, but a new locking feature prevents people from forcing pharmaceuticals into an already full box. Nobody will walk off with this one either. It’s bolted to the ground.

Medicine take-back programs help prevent these chemicals from being flushed or thrown in the trash, potentially contaminating local waterways. Taking in unwanted medicines is a public safety issue too.

“If we can take it here in this box, it means they’re not in somebody’s grasp at home—toddlers take anything they can grab,” said Amy Anderson, Urbana animal control officer/community liaison, who manages the box.

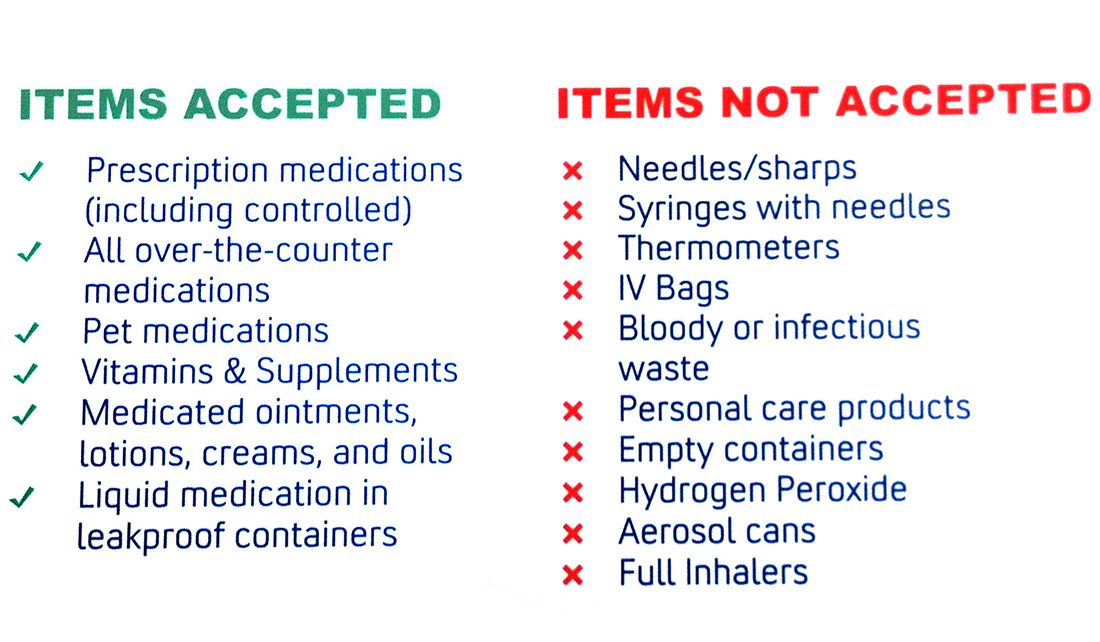

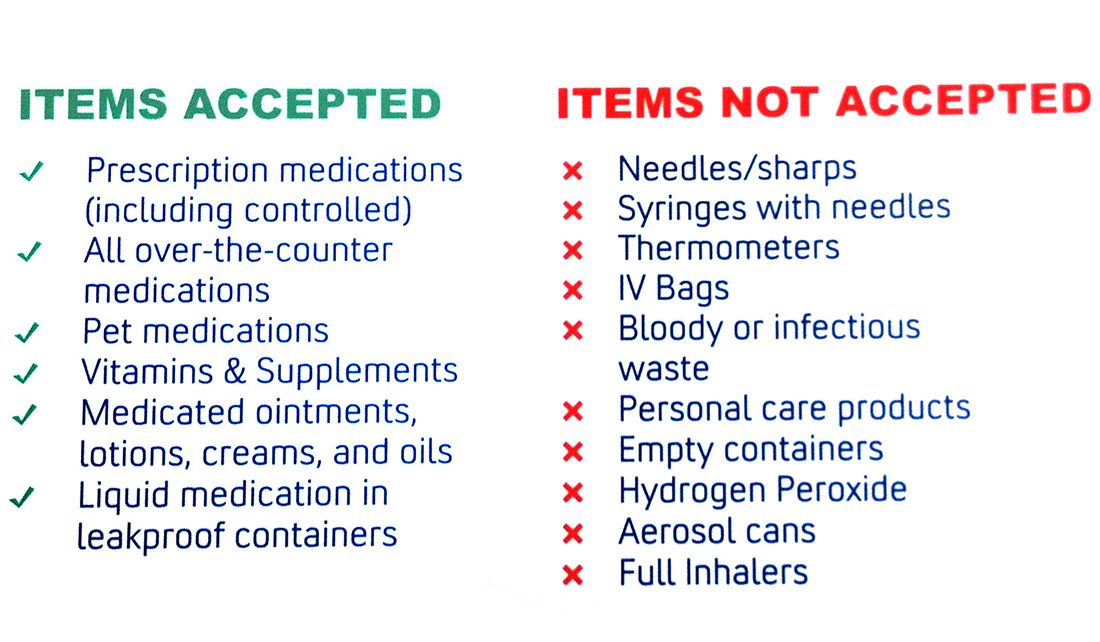

The police department, along with more than 50 locations in four states—including one in Champaign and one at the university—are designated to accept prescription and over-the-counter medicines, including veterinary pharmaceuticals, but not illicit drugs, syringes, needles or thermometers. IISG provides each location with the drug collection box and works with community partners to ensure the program’s success. All collected drugs are incinerated—the environmentally preferred disposal method.

The Champaign and Urbana medicine take-back programs started in 2013 and have collected more than 13,000 pounds of medicine. The IISG take-back program as a whole, which was established in 2007, has collected more than 58 tons. In addition, Sea Grant has helped collect over 30 tons just from helping out in single-day events throughout the Great Lakes region.

Amy Anderson, Urbana animal control officer/community liaison, (left) and Lieutenant Robert Fitzgerald pose with the new medicine take-back box in the lobby of the Urbana Police Department.

“The partnership we have with the Urbana Police Department, Champaign Police Department, and University of Illinois Police Department is so valuable,” said Sarah Zack, IISG pollution prevention extension specialist. “They do a great public service by operating this take-back program, and I hope that people can take advantage of the convenient drop-off locations in the C-U area.”

Be sure to visit unwantedmeds.org to find your local take-back location.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

July 19th, 2017 by IISG

A goldmine of recreational fishing data is now available in one place thanks to researchers and state government officials in Illinois and Indiana.

The website, Angler Archive, www.anglerarchive.org, is the brainchild of Mitchell Zischke, IISG research and extension fishery specialist at who saw the need for having the information more easily accessible when he was doing his own research.

The site currently contains over 50,000 records gathered between 1986 to 2013 by the Illinois Natural History Survey (INHS) and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources (Indiana DNR) in southern Lake Michigan during their seasonal “creel surveys.” Indiana not only surveys the lake but also nearby streams. Zischke will be updating the website as more data becomes available.

Creel surveys are conducted by state officials who interview the anglers while they’re fishing or at the end of their trip. The questions focus on how many fish and what species they caught; how much time they spent fishing; and where they caught the fish.

The website mirrors the creel surveys, but allows users to customize how and what data they want to see. They can use the drop-down menus to display and compare data by angler type, month, and species as well as generate and export the informaiton as a graph.

“In fact, I’m working on a project right now, analyzing data from the 80s and the 90s,” Zischke said. ”I’m finding there seems to be a relationship between the decline in yellow perch and the decline in the number of people fishing and the amount of time they spent fishing. Really, it’s just the beginning of diving into all this data.”

Researchers in both states who head up the creel surveys are looking forward to being able to share the data easily.

“I think it’s great. The more of our info that we collect that the public can see, the better,” said Ben Dickinson, Indiana DNR assistant Lake Michigan fisheries biologist.

“We try to go around to different fishing clubs and stakeholders and present this info, and so it’s nice to have a tool to point people to.”

Anglers frequently ask Charles Roswell, aquatic ecology assistant research scientist at INHS, who assisted in providing the data from the Illinois side, how the data from the surveys are going to be used.

“We have a short write-up on our website, describing how fisheries managers use the data, but I always thought it would be nice to have somewhere to direct people to look at what came out of the surveys, what data were actually collected, and what the data showed,” Roswell said. “This is something I always thought would be useful.”

This information spanning over 31 years will no doubt be useful and more easily accessible to researchers, fisheries managers, and curious anglers. For Zischke the data is already yielding some insights.

“It’s good to be able to look at these data now in a time series, as opposed to having to read a report every year. It highlights some interesting trends in fishing effort and in catch of some species, Zischke said.

“Now we’re in the process of exploring what may have caused some of these trends these through time.”

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

June 26th, 2017 by IISG

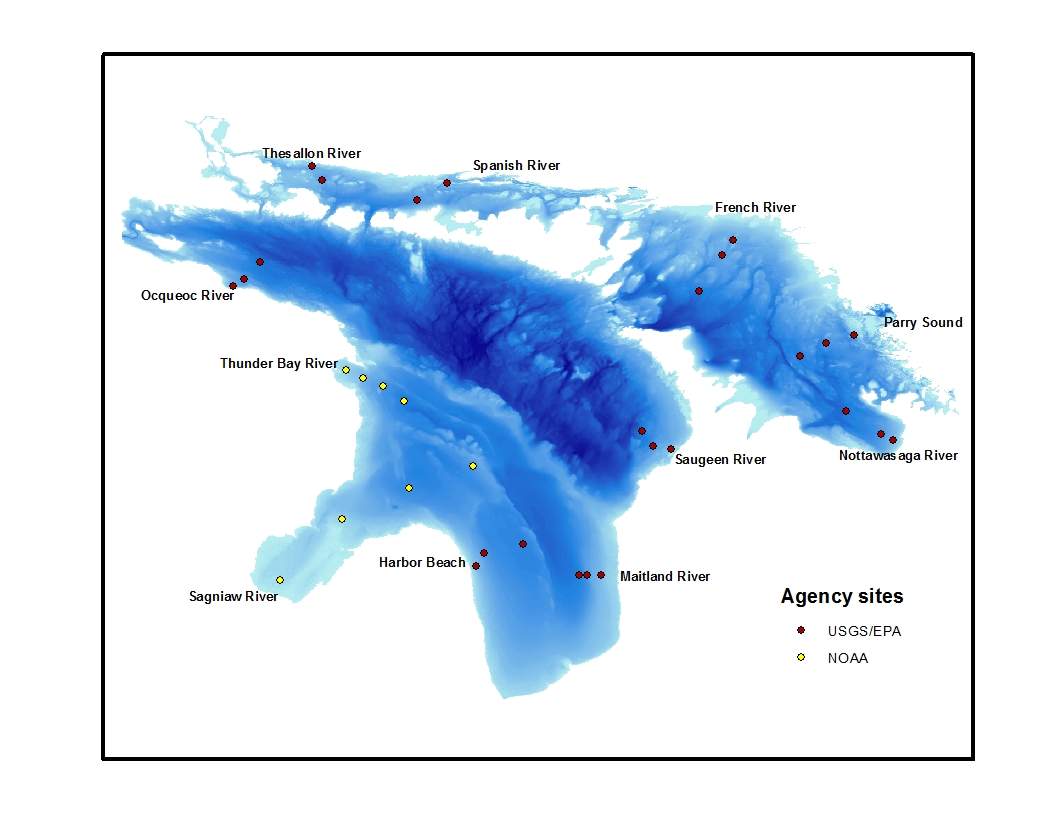

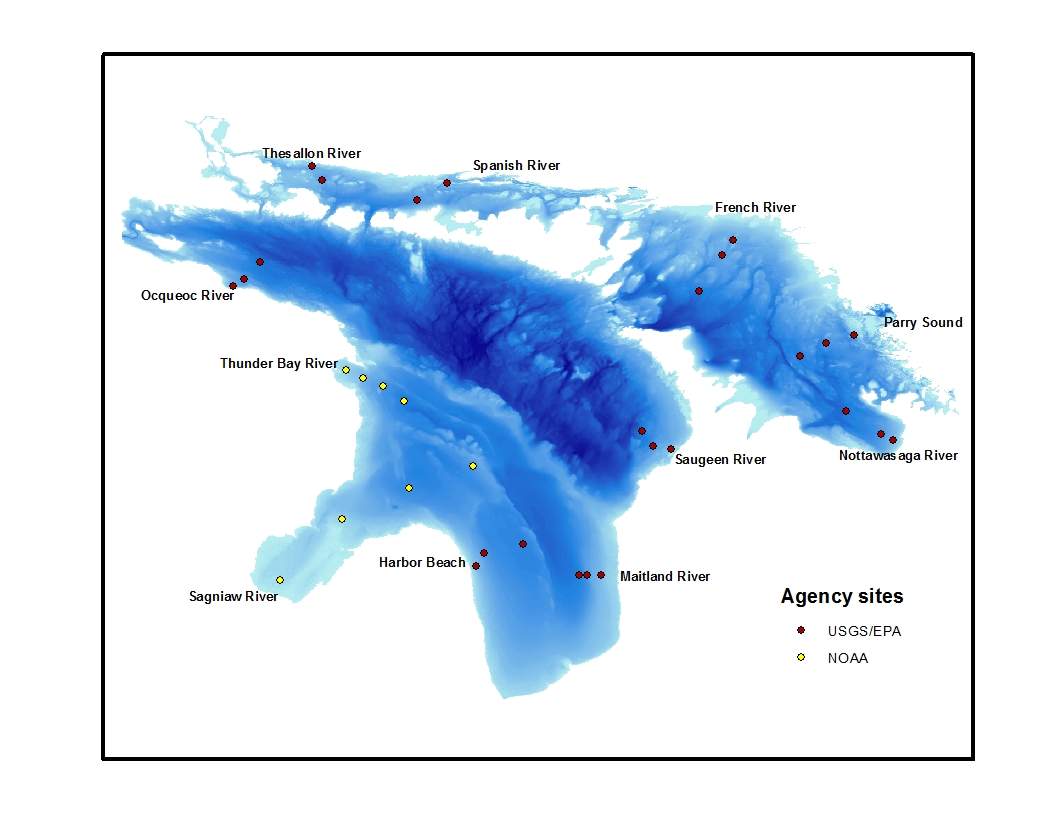

I’m aboard a 180-foot research vessel traversing Lake Huron; the ship is the U.S. EPA R/V Lake Guardian, and the goal is to take the pulse of this gaping freshwater entity. Every year the Cooperative Science and Monitoring Initiative (CSMI) comprehensively surveys one of the five Great Lakes. As a result, it’s been five years since we’ve taken a long look at Lake Huron.

Those working on this particular six-day research cruise vary from marine technicians who live on the ship for the whole sampling season, to scientists from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) onboard for the week to collect data and bring it back to their labs.

Left: A larval fish seen under a microscope. Right: The trawl net used to sample larval fish being pulled in over the sunrise.

And me?

I’m here with IISG as the Great Lakes communication and outreach intern, helping out with the sampling and observing so that when I’m back on land, I can use this experience to enhance my translations of scientific studies from the 2015 CSMI survey of Lake Michigan to engaging, accessible outreach materials for policy makers, fisheries managers, and the general public.

Clark working on the fantail.

I am on the 4 a.m. to 4 p.m. shift of this around-the-clock undertaking. At 3:30 a.m., I’ve got to hastily get up and shuffle down the hall to relieve the night shift on the back deck. I pull on my rain boots, life jacket, and hardhat, then grab a clipboard to record the samples as they come in. There are six sampling sites to complete on this cruise, and each composes a “transect,” a narrow section of water which runs perpendicular to the shoreline, providing an offshore, mid-shore, and nearshore snapshot.

Each station has a sampling agenda. If a station is reached at night, this protocol begins by sampling benthic, shrimp-like animals known as Mysis under red light. If the sun has already risen, we use an extremely large and well-outfitted CTD—an instrument that measures conductivity, temperature, and depth as it is deployed through the water column.

Next up is the zooplankton sampling, followed by two ichthyoplankton tows to sample larval fishes—the early stage in a fish’s life history where they are mere millimeters in length, floating about eating the zooplankton we sampled just prior. The larval fish collected are separated from the various bycatch of flotsam and examined back at USGS headquarters for a variety of parameters including species, length, and age.

The age data, collected by examining growth increments on the larvae’s minute otoliths (inner ear bones), is reported in days old. I find them enormously cute, in an E.T.-without-legs kind of a way.

Map of the CSMI survey stations in Lake Huron. During this cruise Harbor Beach, Maitland River, Saugeen River, Nottawasaga River, Parry Sound, and French River transects were sampled, in that order.

After each of the three stations have been surveyed, a large sampling instrument called the Triaxus is towed back along the entire transect to gather information across the full survey area. Depending on the length of the transect, this can take a while.

I have found this a great time to hit the galley and grab a second or third breakfast, depending on the day. After all, by 9 a.m. I’ve been awake for a good five to six hours and there’s more sampling to do.

We then lower the Rosette, a big water sample collector, to measure the amount of chlorophyll in the water. We also put nets down six different times to collect zooplankton. We then used a big net to collect larval fish out the side or behind at different depths throughout the water column. We also towed the Triaxus for a few hours. We head to the next transect and do it all over again.

And—if we’re lucky—in exchange for all our hard work, the next time I crawl out of my bunk at 3 in the morning I get to witness a scene like this one:

Emily Clark is working with Paris Collingsworth and Kristin TePas as a summer intern with IISG where she is creating outreach materials for the results of the 2015 Lake Michigan CSMI field year. Clark is a student at College of Charleston in South Carolina studying biology, environmental studies, and studio art.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

June 22nd, 2017 by IISG

Unfortunately in the United States we pollute at a rate much faster than we can put control measures in place. New chemicals and substances are continually being developed and used to enhance our industrial processes and products. A drawback to this advancement is that in some cases, when a chemical so novel, we have difficulty understanding the full effects it’s having on the environment or public health. This is what researchers are looking into when they study emerging contaminants.

As part of the IISG pollution prevention team led by Sarah Zack, I attended the Emerging Contaminants in the Aquatic Environment Conference (ECAEC), organized by the Illinois Sustainable Technology Center and IISG. The conference was a two-day crash course on the newest pollutants causing concern for the health of our waterways. Nearly 100 people attended to listen to four invited speakers, 27 contributed talks, and view 18 posters.

While last year’s conference zeroed in on contamination from pharmaceuticals and personal care products, this year we heard from researchers studying a wide variety of contaminants—from harsh-sounding chemicals used for things like flame retardants and stain repellents, to everyday items winding up as litter and microplastic on our beaches.

I found it reassuring to hear from researchers who are working so diligently to understand how these contaminants are getting into our water, how they move through the ecosystem, and their effects on not only the tiniest organisms in the environment, like microscopic plankton but all the way up to humans as well.

One of the four keynote speakers, Barbara Mahler from the U.S. Geological Survey, presented her research on coal-tar-based pavement sealcoat that is sprayed or painted on top of many asphalt parking lots, driveways, and playgrounds. Mahler found that coal-tar sealcoat, and particularly the dust that results from its wear and tear, is a major source of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) contamination. Many PAHs are known to cause cancer, mutations, and birth defects in addition to being acutely toxic to aquatic life. Her work has informed policy in Austin, Texas where she conducted her research, as well as in other states and cities across the country.

Another keynote and familiar face for Illinois-Indiana Sea Granters, Tim Hoellein discussed several projects he’s working on relating to anthropogenic litter—trash that is making its way from people onto our beaches, in our rivers, and ending up in our Great Lakes.

And it’s not just the chemists and biologists who are toiling away on this complex, moving-target-of-an-issue. Having been to my share of scientific conferences, I was impressed at the variety of disciplines represented at ECAEC. Social scientists, educators, and even an attorney (yet another captivating keynote speaker, Stephanie Showalter Otts) also weighed in on the conversation of how to tackle the problem of emerging contaminants.

For me, it was especially cool to hear scientists in the room call out the necessity of working across disciplines and involving social scientists to further the reach of their research. It’s clear that the road ahead will not be easy, but I walked away from this conference feeling encouraged that there are brilliant, innovative people who are working to address these challenges from many angles.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

June 12th, 2017 by IISG

As a new intern with Illinois Water Resources Center, I attended a workshop last month with about 30 people from organizations including Peoria Public Works Department, Peoria Innovation Team, and Illinois Master Gardener and Master Naturalists at the Peoria Public Works building to learn the fundamentals of rain garden design.

Peoria’s interest in installing rain gardens has grown out of a pressing need to manage stormwater to help mitigate overflows from the city’s combined sewers into the Illinois River. Rain gardens can be part of an overall green infrastructure strategy that significantly reduces combined sewer overflows. IISG and the city of Peoria worked together over a year to finalize the details on this workshop, an important step towards addressing the the stormwater issue.

After an early-morning drive from Champaign to Peoria, I had the opportunity to listen to several guest speakers, including Kris Lucius, a landscape architect with SmithGroupJJR, and Eliana Brown, IISG stormwater specialist who introduced the group to rain garden design essentials. We also heard from Jason Haupt, Illinois Extension educator, who discussed details regarding plant species and best management practices for maintaining rain gardens.

Following a brief lunch, Kara Salazar, sustainable communities extension specialist, led the attendees on a group rain garden design scenario activity. Each group was tasked with a specific rain garden scenario that presented different planning obstacles.

Jason Haupt, Illinois Extension educator, speaks during the classroom session at the Peoria rain garden workshop.

My group was responsible for developing a rain garden in a typical suburban home setting. The role and functions of landscape architecture, which I’ve learned from my graduate studies as well as this workshop, can encompass numerous realms, including urban planning and design, architecture, and economic and community re-development.

Tuesday’s events brought many of these fields together. Designing and planting the rain gardens served as both a conceptual and physical implementation of green infrastructure and development. How this small project will serve as a precedent for the City of Peoria is one of many aspects of landscape architecture that interests me.

Cameron Letterly, left, helps distribute mulch at the rain garden build in front of the Peoria Public Works Department.

Darren Graves, intern at the Public Works Department in Peoria, designed the project that the participants then planted in front of the building.

“I wanted to add some color and some diversity in plant material to Public Works Department,” Graves said. “The more diversity we have in plant material creates a habitat for wildflower, pollinators, bees, hummingbirds, butterflies. This is one big cycle that can benefit everybody through our health as well as our crops.”

“I think landscape should be more than just shrubbery,” Graves added.

Anthony Corso, chief innovation officer and director of Peoria’s Innovation Team said this project would help the Peoria Public Works staff “understand what the maintenance looks like of this [rain garden] plan” and that it would serve as a model for what is “supposed to be expanded over two decades into about eight square miles of the city and beyond.”

All the participants gather for a photo in the new rain garden.

I initially had no idea of the scale, nor incredible enthusiasm of the volunteers for this project. However, after consulting the master plan and after digging the numerous holes for plants, I knew this experience was a step towards greater green infrastructure awareness for all involved.

Through our combined efforts, we were not only able to construct a functional rain garden in under two hours, but also able to involve an incredible array of volunteers from a multitude of disciplines.

To best summarize my experience, when our team began a system of handing river stones to each other, roughly defining the edges of the garden, I remembered a quote from earlier in the morning from Peoria Innovation Team’s Anthony Corso, “It’s easier to learn when you do some hands-on.”

Cameron Letterly is a summer intern with the Illinois Water Resources Center (IWRC) where he is currently working on several projects in coordination with Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant. Cameron is a student in the Master of Landscape Architecture program at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and a prospective Illinois MBA candidate.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

June 9th, 2017 by IISG

IISG and Illinois Water Resources Center extend a big welcome to this summer’s interns! The five will be working side-by-side with specialists and scientists on everything from outreach and communication to sample collection and data analysis.

Emily Clark

Illinois-Indiana Great Lakes Communication and Outreach Intern

Paris Collingsworth and Kristin TePas

Emily Clark is going into her senior year at the College of Charleston in South Carolina. At College of Charleston Clark she is a biology major with minors in environmental and sustainability studies and studio art. She has strong interests in aquatic ecology and science communication, which is what led her to apply to this internship.

As the Illinois-Indiana Great Lakes communication and outreach intern working in the Chicago area, she will be learning about the results of the CSMI field year in Lake Michigan from 2015. She is reading the studies that were done, and will be interviewing scientists on their work. Following this research, Clark will be putting together outreach materials for a variety of managers and policy makers to ensure the changes in the lake are taken into consideration. In addition, she will be participating in this year’s CSMI research cruises on Lake Huron helping to collect contemporary data on the Lake.

Lindsey Dice

Lindsey Dice

Fisheries Data Analyst Intern

Mitch Zischke and Tomas Höök

Lindsey Dice is a junior fisheries and aquatic sciences major and Spanish minor at Purdue University. She is a fisheries data analyst with Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant this summer and will be working with charter boats in Lake Michigan to update the Lake Michigan Fish Catch on the IISG website.

Dice will also be analyzing data collected from inland glacial lakes. She will be comparing the relationship between water quality and total catchment area.

Madeline Henschel

Madeline Henschel

Sustainable Communities Intern

Kara Salazar and Daniel Walker

Madeline Henschel be a senior this fall at Loyola University Chicago and is an environmental studies major with a minor in finance. She spent the fall semester of her junior year studying abroad in Australia where she had the opportunity to study environmental management and marine biology. She has also worked with a small neighborhood and business development group in Chicago on a local farmers market that emphasizes the availability of fresh food for shoppers with federal or state nutritional assistance.

Moving forward, Henschel hopes to focus her career on sustainability and the many forms it takes. This summer as the Sustainable Communities intern she will be contributing to case studies for Enhancing the Value of Public Spaces Program, collaborating with the Lake Michigan Coastal Program to create a coastal flooding tool kit for municipalities, as well as support the Extension program by traveling the state attending meetings and community programs.

Cameron Letterly

Cameron Letterly

Illinois Water Resources Intern

Eliana Brown

Cameron Letterly is a summer intern with the Illinois Water Resources Center (IWRC) where he is currently working on several projects, including graphics for the Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy in coordination with Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, revitalization of a university rain garden, and work regarding green infrastructure and real estate value.

Cameron joins IWRC as a student in the Master of Landscape Architecture program at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign as well as a prospective Illinois MBA candidate.

Brandon Stieve

Brandon Stieve

Microplastics Research Intern

Leslie Dorworth and Sarah Zack

Brandon Stieve is a chemistry major, with an environmental science minor, at Purdue University Northwest and expects to graduate in the spring of 2018, after that he looks to start his career. Stieve’s dream job is to be at an environmental testing corporation, studying water toxicity and use that information to help protect the health and well-being of people. He think the area he wants to specialize in is metal toxicity in waterways.

His research project is looking at microplastic concentration in lakes and streams of northwest Indiana. He is working with Kathryn Rowberg, Leslie Dorworth, Sarah Zack, as well as another student, Josh Miranda.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

May 16th, 2017 by IISG

Researchers, federal and state government and non-government officials, students, and representatives from Ohio, Wisconsin, and Michigan Sea Grants gathered at Purdue University recently to take part in the two-day Tipping Point Planner collaboration workshop.

The web tool uses the latest watershed research and cutting-edge technology to show planners how close their watershed is to known environmental tipping points and what the watershed will look like if land use decisions continue “business as usual.”

Planners can also test how developing more in one location or restoring habitats in another moves ecosystems closer to or further from tipping points. With help from a Sea Grant facilitator, planners can use these interactive maps and simulators—along with recommended policies, ordinances, and outreach efforts—to prevent aquatic ecosystems from being degraded beyond repair.

The program’s name is shorter and the homepage has a new look, but the goals for this powerful watershed-planning tool are the same. Some of those in attendance were part of the original team that helped get the program off the ground in 2010 and others were using it for the first time.

The purpose of this workshop was to gather researchers and end-users of this decision-support system as well as partner government agencies to take part in feedback sessions to help inform the development of the upcoming redesign of the Tipping Point Planner website.

Kara Salazar, IISG sustainable communities outreach specialist, has helped communities since 2012 learn how to use Tipping Point Planner in their area. Now Salazar, along with Dan Walker, community planning specialist and Lydia Utley, data analyst, are continuing to expand the tool’s use and functionality.

“Communities plan for many reasons. The Tipping Point Planner process can support a community’s vision for managing land use while minimizing impacts on water quality,” Salazar said.

The first day of the workshop featured talks from researchers from the Great Lakes region followed by breakout sessions led by Purdue researchers on emerging issues. The second day addressed nutrients and food webs, new topics to the Tipping Point Planner tool.

Larry Theller of Purdue gives a talk on “L-THIA works inside Tipping Point Planner.” L-THIA was developed as a straightforward analysis tool to provide estimates of changes in runoff, recharge, and nonpoint source pollution resulting from past or proposed land use changes.

Chelsea Cottingham, watershed specialist at the Indiana Department of Environmental Management sees Tipping Point Planner as a tool for groups she works with that are in the early stages of the land-use planning process. The watershed she manages in northwest Indiana includes agriculture and urban land.

“In large watersheds there are various types of land uses and some of those uses have competing interest in terms of social priorities for the groups of people that live there, as a result we’ve got competing interests,” Cottingham said. “We’re trying to put management practices on the ground to help reduce our nonpoint source pollution and our impact.”

Joe Lucente, Ohio Sea Grant, extension educator, community development, has been involved with Tipping Point Planner from the beginning. Much of his work with communities focuses on economic development and sees how Tipping Point Planner can help.

“We’re trying to gather and see where we’re at in the development of this program and then see how it fits in to the particular community, how we can integrate (Tipping Point Planner) into their comprehensive planning process,” Lucente said. “We’re trying not to take a one-size-fits-all approach, we’re trying to see what makes sense, to see the benefits of it and hopefully start to really put it to use.”

To address that need for more specialized land-use needs, developers of the tool are working to make its calculations more exact to an area.

Edward Rutherford, a fishery biologist at NOAA in Michigan, asks a question during the researcher presentation portion of the workshop.

“It’s still at a watershed basis. We’re making it more goal specific so when a community begins the planning process for a specific topic or goal, we’ll be able to more effectively streamline them through the process,” Salazar said.

“Going forward, we’ll have data maps and information that are tailored to that specific area.”

Tipping Point Planner was developed in collaboration with Purdue University, University of Michigan, Michigan State University, University of Minnesota Duluth, University of Windsor, the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, the Cooperative Institute for Limnology and Ecosystem Research, the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, NOAA, and the Great Lakes Sea Grant Network. Funding for the four-year project comes from NOAA and EPA.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

Lindsey Dice

Lindsey Dice Madeline Henschel

Madeline Henschel Cameron Letterly

Cameron Letterly Brandon Stieve

Brandon Stieve