August 8th, 2017 by iisg_superadmin

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant’s Terri Hallesy and Leslie Dorworth and I pulled up along the river’s edge and parked our car on the gravel road. As our group approached the bank, two majestic egrets took flight looking like purest snow against a backdrop of vibrant blues and green. A bald eagle had been spotted earlier, perched on a favorite branch of a dead cottonwood hanging over the river.

Educators tour Roxana Marsh, a 19-acre restoration site.

It’s hard to believe that five years ago, a brown stand of the invasive species, Phragmites, had dominated the landscape where we were standing. The Grand Calumet River has made a radical transformation over the last 10 years thanks to the Great Lakes Legacy Act and many dedicated federal, state, and local partners. Our mission that day was to help 42 teachers from South Bend, Indiana understand just how large the ongoing transformation is, in hopes that they would carry this inspirational message back to their classrooms in the form of science labs, writing assignments, and other educational activities.

We set out to accomplish this mission by hosting an IISG teacher workshop at Purdue University Northwest, Hammond campus in collaboration with The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the Indiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR), and the Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM).

IISG’s Caitie Nigrelli stands in front of 58 acres of restored wetlands of the East Branch of the Grand Calumet River.

Leslie and I have worked many years on the Grand Calumet River remediation and restoration and led the workshop. IISG assistant, Ben Wegleitner, played a coordinating role. Working together, we brought in partners, Susan MiHalo (TNC), Carl Wodrich (DNR), and Anne Remek (IDEM), to talk about the Grand Calumet River and to host a tour of restored sites along the river.

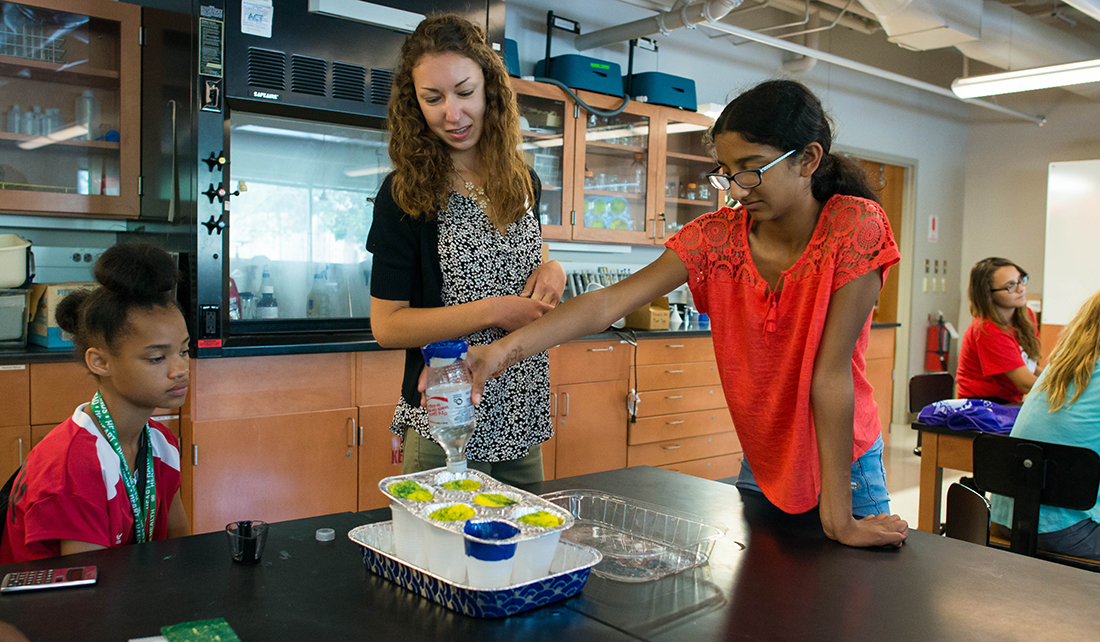

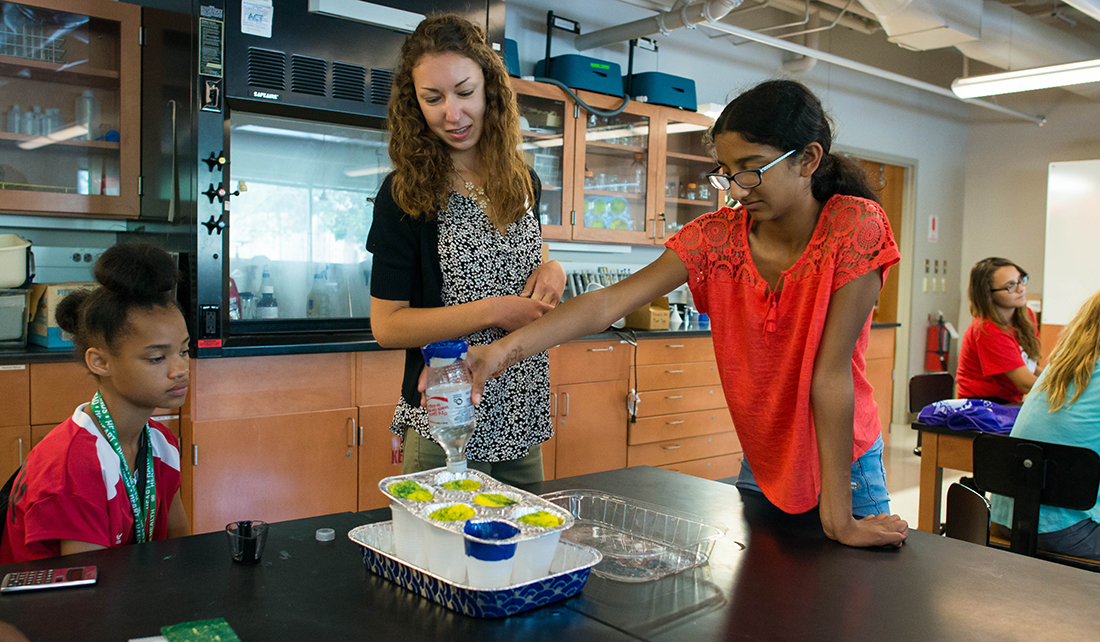

As IISG education coordinator, Terri demonstrated curricula and classroom activities as educators worked in groups, insuring its infusion into existing science curricula.

She shared information about the issue of aquatic invasive species spread by sharing an innovative web site, Nab the Aquatic Invader! This engaging tool introduces students (grades 4-10) to marine and freshwater invasive species and their impacts using a detective theme and cartoon characters. Teachers also learned the environmental issue concerning improper release of classroom animals and plants and the threat they pose to the Great Lakes ecosystem through the campaigns, Habitattitude™ and Be a Hero-Transport Zero ™.

Carl Wodrich (right), Indiana Department of Natural Resources, guides educators on a hike.

Terri explained what she hoped to achieve that day—through direct experience with relevant education resources, these educators are now better equipped to explain how students can play an active role in helping to prevent the spread of AIS and foster a greater awareness of aquatic science.

For classroom activities and curriculum ideas, visit IISG’s Education Products page.

For information on the cleanup and restoration of the Grand Calumet River, visit www.greatlakesmud.org.

Terri Hallesy and Leslie Dorworth also contributed to this article.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

March 10th, 2017 by IISG

The Center for Great Lakes Literacy (CGLL) teamed up with the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum last month to host “Great Lakes Awareness Day: Lake Michigan’s Beauty & Fragility.” CGLL fosters a community of Great Lakes literate educators, students, scientists, environmental professionals, and citizen volunteers dedicated to improved Great Lakes stewardship.

The event featured Great Lakes education and outreach programs developed by Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) specialists, as well as stewardship projects that CGLL-trained teachers have facilitated with their students.

Ayesha Qazi, a horticulture and biology student teacher at Robert Lindblom Math and Science Academy in Chicago, manned a table with her student to show off her “greenhouse” classroom. This new endeavor—that even she admits sounds a little “bizarre”—has proven to be extremely successful.

Ayesha Qazi, a horticulture and biology student teacher at Robert Lindblom Math and Science Academy in Chicago, talks about her greenhouse classroom.

Qazi took part in a CGLL workshop that fosters informed and responsible decisions to advance basin-wide stewardship by providing hands-on experiences, educational resources, and networking opportunities.

“I’m always in the greenhouse, so why don’t I have seating in the greenhouse,” Qazi asked herself.

Qazi said because many of her students don’t have easy access to green spaces, she created a classroom surrounded by lush plants, nice lighting, and fresh air.

And that became a complete game-changer.

“In class if the students get distracted, they’re in a greenhouse, they’re looking at plants. They say it’s so calm and peaceful.”

Christine Miller, a science teacher at Healy Elementary School in Chicago, brought three of her students to staff a table focusing on aquatic invasive species. Her students showcased what they learned about the invasive plant, purple loosestrife, that has crowded out native species in Illinois wetland and marsh areas.

Sarah Zack, IISG pollution prevention outreach specialist, speaks to a woman at her table at the event.

“This event was a great reminder of how engaged people are in Great Lakes issues, and how important healthy water resources are to us all,” said Sarah Zack, IISG pollution prevention specialist who had a table at the event.

“Everyone I spoke to was interested in learning how they could do more to prevent pharmaceuticals and microplastics from entering our waters, which made for a really exciting event.”

IISG specialists Greg Hitzroth, Allison Neubauer, Kristin TePas, Molly Woloszyn, and Irene Miles also hosted tables at the event. Shipboard Science alumna Susie Hoffmann was there to share her photos from her U.S. EPA R/V Lake Guardian experience.

Terri Hallesy, IISG education coordinator, second from left, chats with women at the event.

“With increasing public concern about environmental issues, it is essential that we work together to build a scientifically literate citizenry,” said Terri Hallesy, IISG education coordinator. “Great Lakes Awareness Day events provide an opportunity to broaden understanding of Great Lakes issues to enable a greater number of citizens to become better stewards of the Great Lakes environment.”

“Our ultimate goal is to leave the Great Lakes better for the next generation.”

January 24th, 2017 by IISG

“It was an early morning start with sampling near Stony Point along the northern shores of Minnesota,” Ann Quinn, of Pennsylvania and Krysta Maas, of Minnesota, wrote in a blog post in July of 2016.

“As we approached Duluth, we stopped three times to sample near the shore and within the harbor. As we passed under the lift bridge, we could ‘clearly see’ the sediment plume from Monday night’s tremendous storm.”

Quinn and Maas were two of the 15 educators chosen last year to participate in the annual Shipboard Science Workshop aboard the U.S. EPA’s largest research and monitoring vessel on the Great Lakes, R/V Lake Guardian. Sea Grant’s Center for Great Lakes Literacy (CGLL) with U.S. EPA Great Lakes National Program Office (GLNPO) host the annual program. CGLL, formerly known of Centers for Ocean Science and Educational Exploration, is a collaborative effort led by Sea Grant educators throughout the Great Lakes watershed. This cruise is an important cornerstone of CGLL’s programming.

Every summer since 2006, CGLL joins forces with GLNPO to facilitate this weeklong workshop on one of the Great Lakes. Educators from not only traditional classrooms but also from places like museums, zoos and nature centers are welcome. The experience provides educators in the Great Lakes basin the opportunity to actually “do” science alongside aquatic researchers and learn strategies to integrate Great Lakes science into their curriculum.

IISG community outreach specialist Kristin TePas, who as the Sea Grant liaison with GLNPO accompanies every cruise, never tires of seeing teachers learning and researching in the field.

“I always look forward to watching how the educators take to the whole experience,” TePas said. “They come on rather green and leave at the end of the week looking like they have always lived on the ship, working like a well-oiled machine, taking part in field sampling and then analyzing in the lab.”

The hands-on, immersive nature of the experience fosters a broader and deeper understanding of science by integrating knowledge and research to enhance the teachers’ scientific investigation skills. Educators also expand their “treasure box” of lessons, teaching strategies, and network of like-minded colleagues.

Following their time aboard the R/V Lake Guardian, the teachers return to their classroom with newfound knowledge that they then implement into school initiatives, like organizing cleanups of nearby natural areas, starting real-world data collection and analysis for class projects, bringing scientists into the classroom to talk and work with students, and inspiring school science and environmental clubs.

Alex Valencic, an alumnus of the 2013 Lake Ontario cruise, incorporated his experience into his fourth-grade class in Illinois.

Each student spent six weeks studying a freshwater fish found in the Great Lakes and learned about its appearance, habitat, life cycle, and where it falls in the food web.

“My primary goal is for my students to understand the rich diversity of life that lives within the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Seaway,” he said. “Even though we don’t live right on a lake, Illinois is hugely impacted by Lake Michigan.”

Educators and scientists on recent cruises have taken advantage of a new way to communicate their experiences to those back on land. In addition to filing blog posts on the CGLL website, folks on the cruise have started using Twitter to document their journey while traversing the lake. Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant Educator Allison Neubauer has compiled the tweets into a narrative of the cruise.

“Showing off the collaboration as it’s happening, making it accessible and informative,” Neubauer said, “is a great way to tell the important story of the work being done by the teachers and researchers in only seven days.”

The scientists onboard were equally impressed with the experience.

“A strong scientist-educator connection can bring the research alive as scientists share stories from the field or lab,” wrote Wisconsin researcher Emily Tyner in “Scientist Spotlights,” an ongoing series on the CGLL website.

“But the sharing process isn’t one-way,” Tyner pointed out. “Educators can offer a new and helpful way of looking at problems that stump scientists. Thinking back on my Lake Guardian cruise, the educators helped us gain helpful perspective when we faced hours trying to determine the problems with our experimental setup.”

The educators no doubt would agree. They get the chance—as many have put it—to take part in an adventurous, educational, inspiring, fun, and once-in-a-lifetime adventure!

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

January 17th, 2017 by IISG

August to November of my John A. Knauss Marine Policy Fellowship was non-stop. I have been learning about international fisheries policy in my placement within NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service, Office of International Affairs and Seafood Inspection Program all year and it was time to see it in action. My travels took me to five countries on three continents for five, very different international meetings.

Using the professional development funds provided by the fellowship, I traveled to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in August for the 34th meeting of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR). The conference was directly related to my doctoral thesis work and also tied in with work that NOAA Fisheries does in the Southern Ocean on the United States delegation to the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR). Many scientists from other nations’ delegations were also present at the SCAR meeting and it was an incredible opportunity to meet international Antarctic researchers, many of whom I would see two months later in Hobart, Tasmania for the 35th meeting of CCAMLR.

Lauren in Tasmania, Australia at Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR).

I thought central Illinois and Washington, D.C., were hot and humid during August and that I was well prepared for August in Kuala Lumpur. It turns out that a few higher percentage points of humidity make a huge difference in comfort level. Thankfully my hotel was connected to the convention center, meaning trips outside could be planned strategically. I was also fortunate to be staying at the same hotel as the U.S. delegation to SCAR and they welcomed me into their morning breakfast meetings to learn more about the inner workings of the conference organization.

The conference itself was not only a great way to keep up on the current research in my field of fish physiology but also learn about areas of Antarctic research that I had previously never considered on topics as wide-ranging as algal ecology to architecture and literature. There were a number of panels and sessions devoted to scientific advice for policy which is a topic that is extremely relevant to the Knauss Marine Policy Fellowship as well as my role in my fellowship office. Many of the topics discussed would make a second appearance two months later during the CCAMLR meeting.

Malaysia tea plantation

The 2016 CCAMLR meeting in Hobart, Tasmania was an exciting meeting to attend. Many of the species I was familiar with from my doctoral work were discussed in terms of conservation or fisheries catch allocation in regions of the Southern Ocean that I was familiar with. One of my largest projects of my fellowship year was drafting a background paper for the U.S. delegation to present to CCAMLR on incorporating independent review of fisheries stock assessments in the CCAMLR convention area.

I was able to be in attendance as a member of the U.S. delegation and see this paper brought to the floor in front of the 24 member nations and the European Union and discussed. The most exciting event to come out of the meeting, however, was the passing and adopting of the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area, a 1.55 million square kilometer section of the Southern Ocean set aside for conservation. This proposal, which is also the world’s largest marine protected area, was six years in the making and its adoption was met with applause, hugs, and tears from the nearly 250 people in attendance at the meeting. It was an emotional and exciting meeting to be a part of.

My fellowship is coming to an end, but I will be continuing my work with NOAA Fisheries as a full-time employee and foreign affairs specialist beginning on January 23. I am so grateful for the experience and training that this fellowship has provided to me this year.

Please visit the Fellowship and Scholarship page for more opportunities.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

January 13th, 2017 by IISG

For the month of January, the Sea Grant 50th is focusing on K to Gray education—yes, that includes everyone—and within IISG there is no shortage of resources for all ages.

Terri Hallesy who has been with the IISG education team for 13 years has seen teaching trends change over the years, but in the end, she knows it’s really very simple.

“I just enjoy working with all the dynamic, engaging specialists,” Hallesy says. “They each focus on diverse programs and target different audiences. What’s great is they’re always ready to collaborate using the latest and most relevant educational tools.”

Below we are highlighting five of the projects the education team has produced—in collaboration with specialists, other Sea Grants, as well as educators—that capture that cooperative spirit.

Nab the Aquatic Invader!

Nab the Aquatic Invader!

Launched in 2009, this website focuses on the suspects–aka the invasive species–in four regions of the country: Atlantic, Pacific, Gulf, and Great Lakes. In each region, visitors can see read interrogation interviews with the 10 Most Wanted AIS and learn their origin, problems they cause, and some control methods used to slow the spread of these species. The project was featured in the Smithsonian in 2010.

Collaborators included New York, Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Ohio Sea Grants.

The Medicine Chest

The Medicine Chest

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant’s (IISG), The Medicine Chest, invites high school students to metaphorically open up those doors and investigate what makes those chemicals harmful to people, pets, and the environment when improperly disposed. The curriculum was updated last year.

Collaborators included Pennsylvania Sea Grant, U.S. EPA Great Lakes National Program Office, and Paul Ritter and Eric Bohm, P2D2 Program Administrators.

Sensible Disposal of Unwanted Medicines

When medications are flushed down the toilet, wastewater treatment plants can’t always filter out the harmful chemicals that can affect wildlife and even get into drinking water supplies. This 4-H guidebook and curriculum, designed for informal education audiences, provides five inquiry-based lessons to help high school youth understand the harmful effects of improper disposal of medicines and what they can do to help.

Collaborators included 4-H and Penn High School, Mishawaka, Indiana.

Fresh and Salt

Fresh and Salt

Fresh and Salt is a collection of activities that enhance teacher capabilities to connect Great Lakes and ocean science topics. Designed to be used by teachers in grades 5-10, this curriculum provides an interdisciplinary approach to ensure that students achieve optimum science understanding of both Great Lakes and Ocean Literacy Principles.

Collaborators included Centers for Ocean Science Education Excellence and Ashland University.

Lake Michigan by the Numbers

Lake Michigan by the Numbers

This curriculum was created by teachers who attended a day-long workshop to learn how to incorporate buoy data into their classroom instruction. They created these data-rich, STEM-based lesson plans that boost understanding of Great Lakes issues by incorporating real-time data from Great Lakes buoys.

Collaborators included Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Lake Michigan Coastal Program, and Center for Great Lakes Literacy.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

October 12th, 2016 by IISG

This story first appeared on LakeScientist.com.

The Limno Loan program, overseen by the Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, is making it easier for educators around the Great Lakes to teach their students about freshwater science. Not only that, but it’s also inspiring youngsters who have never gotten to use real scientific gear.

The program, which launched in the 2011-2012 school year, began after suggestions from teachers taking part in a science workshop on the Lake Guardian Research Vessel. The workshop on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency ship led them to think that it’d be a great idea to get some of the same gear into the hands of their students.

The Limno Loan program of today is pushing the boundaries of success, providing four Hydrolab DS5 water quality sondes to high school and middle school teachers around the Great Lakes. Each gets the sondes for about two weeks, including shipping time to and from the Sea Grant, to use in their lesson plans.

That first year, the program only had about five teachers who checked out sondes. This year, more than 20 have already signed up and the pace signals to program managers that nearly 40 could use them by the end of the school year.

“High school and middle school students use them the most. That’s the most appropriate age for this type of equipment,” said Kristin TePas, community outreach specialist with the Sea Grant. She says the youngest who’ve used the Hydrolabs were fifth graders. “Most I’d say probably just deploy them in a river or small water body but some have rented boats to take their students out onto lakes.”

When that’s the case, it’s common that the educator secures some sort of grant to cover the cost. And there are usually educational discounts that can help.

“That is one of the hurdles to getting them out there,” said TePas. “You need to have money to do those field trips.”

Loaning the sondes out to teachers provides a substantial cost savings over purchasing. Each one records a standard set of parameters, including temperature, conductivity, pH, dissolved oxygen, chlorophyll a, turbidity and depth.

The measurements are incredibly intriguing to students, who can see how their local water body is doing in real time. But since most of the sampling trips hit ponds on campus or streams nearby, depth is not as important as the other data coming in.

“For some, the lesson is just doing a pond day. … Some are just doing a snapshot in time. Others have a monitoring program and they’re comparing the data that they’re getting,” said TePas. “They might compare between two sites or between different areas. It’s more of a comparison spatially than temporally.”

TePas points out that the sondes have a lot of advantages over other methods the kids may have used in the past. Water quality testing kits often use tablets or strips that can introduce complexity. And the projects sometimes take longer because of that.

One big advantage that the Limno Loan program provides to school kids is that they actually get to use real scientific gear.

“For some reason, just using equipment that’s used by real scientists gets them more excited. It’s instantaneous,” said TePas. “They’re able to see right away what the status of the particular lake is.”

The teachers benefit as well. Long before students get their hands on the sondes, Sea Grant officials give them hands-on training to use the gear.

The training is provided during workshops, TePas says, typically during other activities in partnership with local groups. Because of that, they can take various formats, but the training is consistent throughout.

TePas says it usually starts with the parameters, covering what they measure and what their levels mean when it comes to aquatic health. A few suggestions for activities or coursework that the teachers could use are also thrown in.

“Then we show them the logistics of using the equipment,” said TePas. “The only thing they have to calibrate is DO (dissolved oxygen) when they get it.”

The busy season for the Limno Loan program typically coincides with the school year, it seems. Most of the sondes get checked out in September and October during the fall. When winter comes, TePas and others can’t send them out because of the risk of frost damaging the sondes and their sensors. But things pick back up with educators once again borrowing them in April, May and June.

With those restrictions, it’s not likely that the sonde-sharing program could get any bigger than it is currently. The equipment also gets used by Sea Grant educators when not in use by teachers.

But it’s certain that the program is providing benefits for teachers and students in the Great Lakes. In just the few years it’s been running, TePas says the sondes have gone from schools in New York to Minnesota and everywhere in between.

“First and foremost, I want to increase water quality literacy. … I hope at least they take away a better understanding of water quality. So why do we care, why do we measure this stuff?” said TePas. “And if we had some budding scientists come out of this, that would be awesome.”

About Daniel Kelly

Daniel covers monitoring, tech and everything in between as editor of the Environmental Monitor. You can also find his work on Lake Scientist. Connect with him on Twitter @danielrkelly.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

August 23rd, 2016 by IISG

“The site doesn’t glow!” assured Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (Michigan DEQ) geologist Sarah Pearson, to the relief of local teachers stepping foot on the land of what used to be the Zephyr oil refining facility in Muskegon, Michigan. The site is now home to a fertilizer company.

The 14 educators were taking part in a week-long West Michigan Great Lakes Stewardship Initiative that brought them to an area of wetlands that endured repeated oil spills during the decades prior to the 1990s that Zephyr was in business—refining, then switching to bulk storage.

Teachers gather to look at a map of the Zephyr site.

Today there’s little visible indication of those frequent spills, which sometimes resulted in fires. Now and then you can still catch a whiff of oil or spot some sheen on the ground, but for the most part the landscape is picturesque.

The grasses are tall and the wildlife has started to return. But contamination, including petroleum products and heavy metals like lead and copper, remain just out of site in the sediment of Muskegon Lake.

“The funny thing is that you knew it existed, back in the day. But when we drove back there, you couldn’t see it. So it’s more out of sight, out of mind,” said Shannon Delora, Muskegon area transition coordinator for students in special education.

“Unless you are taken there, you don’t know all that’s happening, the good and the bad of it all.”

Tanks that at one time stored oil by Zephyr are now used by a fertilizer company that owns the land.

Ben Wegleitner, IISG social science outreach assistant, was on hand to introduce the latest version of Helping Hands, a curriculum that engages upper elementary and high school students in Great Lakes environmental stewardship. It is designed for schools located in Areas of Concern, like Zephyr, but can be applied to any Great Lakes community where large-scale environmental cleanup projects are ongoing.

The lessons touch on a variety of topics, like the effects of pollution and invasive species, and include hands-on activities.

“If you need an opportunity to get your students out in the field and get involved in natural resources and pollution,” Wegleitner told the teachers, “there’s no shortage of opportunities to get your kids interested. Muskegon is a uniquely positioned area for that.”

“If you need an opportunity to get your students out in the field and get involved in natural resources and pollution,” Wegleitner told the teachers, “there’s no shortage of opportunities to get your kids interested. Muskegon is a uniquely positioned area for that.”

The Zephyr cleanup, which is funded through the Great Lakes Legacy Act, involves the U.S. EPA, Michigan DEQ, and IISG. The plan is to remediate 36,000 to 45,000 cubic yards, followed by habitat restoration. It’s slated to get started within the next six months and will take about a year and a half to complete.

“I was very unfamiliar with Zephyr,” said Beth Sipperley, a third grade teacher at Oak Ridge Elementary School.

“To go there and see it and to have the curriculum that really ties into it—one that’s so connected to Muskegon—is great.”

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

July 29th, 2016 by IISG

Listen to Kristin TePas’ radio interview with University of Illinois Extension’s Todd E. Gleason below.

Fifteen educators are once again on dry land recovering from a schedule just as packed as the Lake Guardian’s quarters. The 2016 Shipboard Science Workshop on Lake Superior aboard the U.S. EPA Great Lakes National Program Office research vessel wrapped up last week. The annual workshop was hosted by Center for Great Lake Literacy and led by Minnesota Sea Grant.

Using state-of-the-art sensors, the teachers, alongside four research scientists from Minnesota and U.S. EPA, took part in water sampling—all day and night—to evaluate the presence of zooplankton, aquatic invasive species, and water quality and nutrient differences over time.

Teachers working in the lab on the Lake Guardian.

The teachers analyzed the samples in on-board laboratories and presented their findings after the ship dropped anchor. But their work is just beginning. The teachers now have the task of inspiring their own students to become Great Lakes scientific explorers.

“So many of our labs we do in class, the students have to do an experiment that simulates what would happen in real life,” Ashlee Giordano a science teacher at Northfield Jr./Sr. High School in Wabash, Indiana. “It is meaningful, however, showing students what I did, and the data we collected would really hit home for them.”

This year’s cruise received some special attention from University of Illinois Extension’s radio personality Todd E. Gleason who interviewed IISG community outreach specialist and liaison to U.S. EPA Kristin TePas over the phone while she was still on the trip. The interview was aired on stations throughout Illinois.

“We really want them to be more comfortable with science and understanding the process of research,” TePas said.

This year the teachers hailed from seven Great Lakes states. Two were from Illinois and one from Indiana.

The exhaustive effort scientists go through was not lost on Cheryl Dudeck, a biology and human anatomy teacher at King College Prep High School in Chicago.

“I was surprised by how many people it takes to complete one week of research. I also was surprised to find out that the research happens 24/7 and how it changes with the weather conditions,” Dudeck said.

“I think that most people do not understand the importance and complexity of the Great Lakes.”

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

July 26th, 2016 by IISG

When I started working at the Illinois Water Resources Center in May, I had no idea what kind of summer I had signed up for. Needless to say, I hit the ground running. On my third day, we traveled to Chicago for an overnight meeting with IISG, and other state agencies. We discussed current issues, future plans, plus introduced new employees, and interns, like myself. In an unfamiliar place with new people and environmental issues new to my knowledge, I was welcomed warmly, and always encouraged to express my thoughts and opinions.

Next, a rainy Memorial Day weekend came, and with a newfound perspective of water’s role, I traveled across the state to Quincy, Illinois to visit my grandmother. Without having to do much searching, water’s effects were all around me during the trip—the green grass, beautiful flowers, wildlife, woods, and bluffs near the Illinois, and Mississippi rivers. Feeling refreshed, I started diligently planning and working on the blog for the summer. I researched, and wrote my first post on the Fox River in northern Illinois, which seemed appropriate given my recent trip to Chicago. I also went to several video shoots for various outreach projects.

I later attended the Agriculture Water Quality Partnership Forum tech-subgroup meeting in Springfield, as well as the Nutrient Management Council meeting in Champaign. The Illinois Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy—something I studied in my agriculture classes—was put into action as the different agencies, and organizations worked together. In contrast, I then had the privilege of interviewing my dad about what conservation practices he implements on our family farm. It was amazing to not only first-hand explore these issues, but to apply, and build upon concepts I previously studied.

As someone with a strong agricultural and farm background, I realize the importance of sustaining land, wildlife, and of course, the human population. As increasingly more people move to urban environments, and are further removed from agriculture, education will only continue to be more important. I cannot wait to start my senior year at Illinois State University, apply to graduate schools, and pursue a career in natural resources as well as environmental and agriculture education. I am extremely grateful for the opportunities the Illinois Water Resources Center has given me, and even more so, the wonderful people I am fortunate to have worked with.

Ashley, center, helps out the campers with a stormwater workshop earlier this summer in Peoria, Illinois.

Overall, the passion my co-workers have for water related issues is truly inspiring. The wealth of knowledge, and variety of personal and educational experiences creates a very interesting dynamic. I am leaving better versed on nutrient issues, stormwater, green infrastructure, and how all agencies must collaborate to solve problems.

Through teaching an educational STEM camp, interviewing farmers, attending meetings, video shoots, and tweeting I became a better agricultural communicator. Blogging regularly also made me a stronger writer, researcher, and critical thinker. In reality, there is no cut-and-dry answer or formula to solve all environmental issues. It is something we all must work together and compromise on in order to improve, and sustain water resources, and all life that depends on it. No matter where you live, water is something not to take for granted, but to embrace. After all, we would not be here without it.