May 2nd, 2018 by iisg_superadmin

University research projects often include an opportunity for a few students to get real-world field or laboratory experience. At Loyola University Chicago’s Micro Eco Lab, biologists Tim Hoellein and John Kelly have often found ways to connect students with their work. But when they set out to implement the lab’s recent Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant project, opportunities for students really took off.

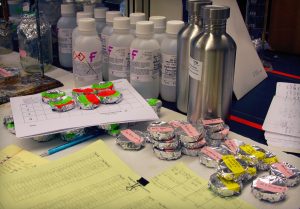

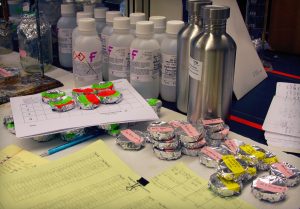

To accomplish this ambitious, comprehensive study to assess microplastic levels in Lake Michigan waterways efficiently and timely, Hoellein and Kelly brought on a post doc to oversee the project. Rachel McNeish looked to students to get much of the work done and the pool of helpers grew to dozens—35 in all, including graduate, undergraduate, and high school students.

“Students were involved with fieldwork, sampling and processing,” said McNeish. They did all the lab work, including data curating—making sure it was entered correctly. Some students have been in charge of specific aspects of the process, making sure it is happening as it should. They then have an opportunity to take a portion of the dataset, analyze it, and present it on campus or at professional conferences.”

For Masters student Lisa Kim, her time spent working on microplastic research and outreach turned out to be life changing. She started her undergraduate tenure at Loyola as a pre-med student, but changed directions after her experience working on the Sea Grant project. “I really fell in love with lab work—getting samples and processing them, and then data analysis and even presenting the results on campus,” said Kim.

She is now an author on the first journal article from the IISG microplastic study, which thus far has found plastic microfibers in the water, sediment and fish in three main Lake Michigan rivers.

Kim is also working on her own research and is exploring opportunities to engage in outreach and in the policy process. “I really want to communicate information about microplastic pollution with everyone. I feel like I got experience working in the lab and doing research, but now I want to bridge the gap between scientists and the community.”

The students come from diverse backgrounds, including some who are first generation college students, and bring a range of interests and experiences. Many are new to the tasks at hand.

“My first time in the field was quite the challenge, balancing being in the canoe with sediment samples and other heavy equipment, all while trying to collect different types of samples from the water,” said Melissa Achettu, a Loyola junior.

Achettu, who has now been working on the IISG project for 18 months, has been funded by two Loyola fellowships to help with the study and to present findings at an international conference this spring.

With Loyola’s setting in Chicago, some students are also experiencing nature and camping for the first time. And with such a busy lab, they are developing leadership skills and learning to work together.

“I enjoy working in the lab with so many other students because it’s a great learning experience when people of so many backgrounds come together,” said Achettu. “Everyone has their unique inputs and ideas. We all learn patience, teamwork and communication skills.”

McNeish puts herself in that camp. “Undergraduate students have just been phenomenal the whole time I’ve been doing research and throughout my education,” she explained. “I feel like I can teach them many things, but they can also teach me a lot too. It’s a two-way learning system. And working with a large group, everyone has something to learn.”

As the research wraps up, McNeish herself is moving on to a new opportunity. She will start a tenure-track faculty position at California State University Bakersfield this August where, as a freshwater scientist, she plans to develop her own student-focused research program.

December 12th, 2016 by Sarah Zack

From his lab at Loyola University Chicago, aquatic ecologist Tim Hoellein investigates the interactions between common pollutants and organisms in rivers and streams. After several years of investigating microplastics in waterways flowing from Lake Michigan, he has now turned his sights to beginning to document the impact of microplastics carried into the lake.

In this new large-scale study, Hoellein and his team are quantifying how much rivers contribute to the plastic load in Lake Michigan by measuring plastics in water and sediment in several of the largest tributaries feeding the lake. In this twelfth and final issue of UpClose, the award-winning Q&A series gives readers an insider’s view of research on emerging contaminants. Each interview highlights a unique component of emerging contaminant research. Readers also learn about the complex, and sometimes tricky, process of conducting field studies and the potential implications of research on industries and regulations.

“The impacts of emerging contaminants on human and environmental health can be hard to document, let alone understand in the context of other issues facing Lake Michigan and other waterways in the Great Lakes basin,” said Laura Kammin, IISG outreach program leader. “The researchers highlighted in the UpClose series each tell a piece of this very complex story.”

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

October 4th, 2016 by IISG

Every month, the Center for Great Lakes Literacy (CGLL), a close partner with IISG, selects an outstanding scientist who embodies the CGLL mission and inspires people to take action to improve the health of the Great Lakes watershed.

This post originally appeared on the CGLL website.

Tim Hoellein

Associate Professor

Research Institution: Loyola University Chicago

Home state: Illinois

What got you interested in science and how did you end up as a Great Lakes scientist?

My interest in ecology is firmly rooted in where I’m from. I grew up in Edinboro, Pennsylvania, near Erie, and later lived in Pittsburgh and went to college in Buckhannon, West Virginia. My experiences in natural areas were places like Presque Isle, Point State Park, and Seneca Rocks. These are some of the most beautiful places in the world. The lakes, hills, rivers, and four seasons speak directly towards a sense of identity for those of us from the area. It is a landscape of extremes, because this region also has a heritage of heavy industry. Manufacturing and mining are important components of our cultural identity and provide the basis for commerce and quality of life. However, the history of mineral extraction, manufacturing, and contaminant storage left a legacy of insidious pollution throughout the region. My motivation for research in water pollution is rooted in that view so common in the Great Lakes and western Pennsylvania: the green and blue of Presque Isle in one direction and the smoke and metal of Erie’s industrial waterfront in the other. My overarching career goal is to work towards a restoration of ecological integrity within the urban and industrial areas where we work and live.

Describe your research related to the Great Lakes.

I study the interaction between common pollutants and the organisms living in streams and rivers of the Great Lakes region. Water quality in the lakes strongly depends on what we put into the tributaries. The pollutants I study include nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, which when in excess contribute to noxious algae blooms in the lakes, and small plastic particles, which affect microorganisms, insects, and fish that sustain aquatic food webs. In particular, I’m interested in how those materials move through streams and rivers, and whether they can be broken down, processed, or retained in streams before they go downstream. This requires first determining the sources of nutrients and microplastic, then measuring the interactions with those materials and microorganisms active in decomposition, and then determining how far downstream the chemicals are transported and how they are incorporated into food webs.

Describe an experience you have had working with educators or the community. What was something that surprised you or that you especially enjoyed about the experience?

I was fortunate to spend a week on Lake Michigan aboard the research vessel Lake Guardian, with a group of teachers from throughout the Great Lakes. We collected samples from the surface water and sediment throughout the lake, and I walked the teachers through the process of isolating plastic particles, including digestions, filtration, and counting particles on the microscope. One of my favorite things about the experience was the enthusiasm that the teachers brought to topic, and how each of them used their own unique talents to come up with creative ways to explain our work in their classrooms. One of the teachers brought a video camera to interview me, detail the collection and counting processes, and give his students  and understanding of how and why we were doing this work. Another used video editing skills and a Go-Pro camera on the sampling equipment to put together fantastic videos of the devices we sent to the bottom of the lakes. This reinforced to me that teachers are at their best when they are using their talents, enthusiasm, and dedication to convey information in creative ways. I try to carry that spirit with me in my role as a teacher in the college classroom.

and understanding of how and why we were doing this work. Another used video editing skills and a Go-Pro camera on the sampling equipment to put together fantastic videos of the devices we sent to the bottom of the lakes. This reinforced to me that teachers are at their best when they are using their talents, enthusiasm, and dedication to convey information in creative ways. I try to carry that spirit with me in my role as a teacher in the college classroom.

Why do you think it is important for scientists to share their research with educators?

In my role as a scientist and teacher, I’ve added to my focus on my studies and students, by looking for more creative ways to share the mission of my work, which includes community service, speaking with students of all ages, and engaging the general public and teachers whenever possible. I’ve found the time spent doing this spreads the message of the research to a broader audience, and deepens my appreciation for the career I’ve developed. Speaking with educators like those on the research cruise on the Lake Guardian was one of the best ways for me to communicate in this way, as the teachers can take that information to their schools and classrooms.

What do you think are the most critical skills for students interested in a career in science?

Science requires a combination of lots of different skills. There are the obvious ones like attention to detail, curiosity about the natural world in all its forms, and the ability to think logically. One often overlooked ingredient for making a good scientist is an open mind with creative impulses. In order to make the step from one project to another, or the first step in a new project, a scientist has to come up with a new question to answer. This requires being interested in lots of different topics, being able to think about combining facts and ideas in new ways, and then creatively and carefully explaining those ideas to collaborators, funding sources, and students.

Contact Tim Hoellein at thoellein@luc.edu.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

June 20th, 2016 by iisg_superadmin

Not all non-native plants and animals turn out to be invasive in a new environment. How can we predict whether a species poses a threat to local waters? If we could predict that, how can we make the best use of that information?

IISG and University of Notre Dame researchers set out to answer the first question by analyzing which traits help a species thrive in a new environment. They brought this data to an Indiana working group looking to proactively prevent the introduction of invasive plant species through water garden and aquarium retailing. The group of researchers, resource managers, retailers, and hobbyists created a risk assessment tool and their work led to 28 aquatic plants being banned in the state.

As a result of this work, Notre Dame’s David Lodge, and Reuben Keller, now with Loyola University Chicago, were funded through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative to create risk assessment tools for all taxa in the Great Lakes, including crayfish, fish, mollusks, plants, and turtles. These tools can help decision makers establish consistent and comprehensive regulations focused on species that pose the biggest threat.

Meanwhile, IISG’s aquatic invasive species (AIS) team has been pulling out all the stops to distribute information that can help prevent the spread of AIS in trade—in other words, species that are bought and sold for water gardens, aquariums, and to a lesser extent, classrooms. Leading the effort as part of the Great Lakes Sea Grant Network, and informed by social science research from North Carolina State University, the specialists are targeting all levels of this AIS pathway—from retailers to hobbyists—and sharing information across the region through a variety of media.

The suite of tools contains publications for retailers and their customers that include lists of non-invaders as well as known or potential invaders. “Many of these resources are informed directly from the risk assessment findings,” said Pat Charlebois, AIS outreach coordinator.

Great Lakes Sea Grant programs and the Sea Grant Law Center are contributing their expertise. For example, Wisconsin Sea Grant created a training video for water garden retailers, and Ohio Sea Grant hosted a webinar for aquarium hobbyists. In addition to writing news articles, other programs helped craft non-technical versions of relevant state regulations to give retailers easy access to the information.

All of this work is raising awareness and potentially changing behavior. “Most of the retailers that have received materials about the risk of AIS have reported that they will distribute publications and talk with their customers about invasive species, and a majority will avoid selling them,” said Greg Hitzroth, IISG AIS outreach specialist.

You can find these resources and many more on the new website Aquatic Invaders in the Marketplace (AIM) or TakeAIM.org. AIM are aquatic plants and animals available for sale that can negatively impact ecosystems, economies, or public health. These organisms are commonly found in the live food, aquarium, pet, biological supply, live bait, water garden, and aquaculture industries.

This comprehensive resource provides a wealth of information for resource managers, retailers, hobbyists, aquatic farmers, and more on how to prevent the spread of AIS that can happen with plants and animals that come to new environments through the marketplace. The website includes links to regulations, lists of contacts and invasive species, and species prediction tools for the Great Lakes and beyond.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension.

June 10th, 2016 by IISG

With the peak of summer right around the corner and gardening season in full swing, we’d like to use this moment as a reminder to be careful about what you choose to plant – particularly if you have a water garden.

With the peak of summer right around the corner and gardening season in full swing, we’d like to use this moment as a reminder to be careful about what you choose to plant – particularly if you have a water garden.

A departure from traditional dirt landscaping, water gardens come with their own set of complications and challenges when it comes to the spread of invasive species. Some key things to keep in mind – make sure your water garden is not near any waterways or flood-prone areas to reduce the risk of any species spreading to natural areas, and always rinse off any dirt or debris from all parts of the plant before planting, to get rid of any potential eggs, animals, or unwanted plant parts and seeds.

If you are planning on cultivating a water garden this summer, and would like more information, check out our brochure and handy wallet card for tips and guidelines on what precautions to take during the gardening process, as well as lists of what plants to grow and what plants to avoid.

These lists are the product of research conducted at Loyola University Chicago and University of Notre Dame, taking into account biological characteristics such as rates of reproduction and climate tolerance to determine which plants are most likely to become invasive. On the flip side, horticulturists and scientists from the Chicago Botanic Garden were consulted to figure out what native or non-invasive plants are the best alternatives. With this information, we hope you are successful in making your water gardens a little safer, and your summer a little more beautiful.

For more information on invasive species and what you can do to help, visit TakeAIM.org.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension.

December 3rd, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

Residents of Illinois, Indiana, and the broader Great Lakes region will benefit from new IISG research. Altogether, the four, two-year projects will receive more than $780,000 starting in 2016.

Residents of Illinois, Indiana, and the broader Great Lakes region will benefit from new IISG research. Altogether, the four, two-year projects will receive more than $780,000 starting in 2016.

John Kelly, a Loyola University biologist, will survey eight major rivers around the lake to trace the origins of microplastics pollution and what river characteristics—such as

surrounding land use or nearby wastewater treatment plants—may be driving this.

Purdue University’s Zhao Ma will lead an interdisciplinary team that seeks to reduce nutrients, sediment, and E. coli contamination in southern Lake Michigan. The team will use models to assess best management practices (BMP) for reducing runoff and the willingness of individuals to implement these BMPs. Looking at these two approaches together will allow them to optimize the best courses of action to reduce overall pollution.

A project led by Sara McMillan, who studies biogeochemistry and hydrology at Purdue University, will examine drainage ditch design from multiple perspectives. McMillan will compare designs that improve long-term stability and ecological effectiveness.

And Beth Hall, Midwestern Regional Climate Center director, will work with Paul Roebber of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee to improve how flash flooding events in urban centers are predicted and communicated. Hall and Roebber’s project is partially funded by Wisconsin Sea Grant.

and understanding of how and why we were doing this work. Another used video editing skills and a Go-Pro camera on the sampling equipment to put together fantastic videos of the devices we sent to the bottom of the lakes. This reinforced to me that teachers are at their best when they are using their talents, enthusiasm, and dedication to convey information in creative ways. I try to carry that spirit with me in my role as a teacher in the college classroom.

and understanding of how and why we were doing this work. Another used video editing skills and a Go-Pro camera on the sampling equipment to put together fantastic videos of the devices we sent to the bottom of the lakes. This reinforced to me that teachers are at their best when they are using their talents, enthusiasm, and dedication to convey information in creative ways. I try to carry that spirit with me in my role as a teacher in the college classroom.