August 31st, 2017 by IISG

Too much of a good thing wore out the old medicine take-back box at the Urbana Police Department, so it recently received an upgrade.

“People come in here all the time and fill this thing up,” said Lieutenant Robert Fitzgerald. “The old one would fill up twice a week. It would just get packed.”

Since the department installed the box in 2013 as part of Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant and University of Illinois Extension’s medicine take-back program, it’s only grown in popularity. This box’s new style still resembles a mailbox, but a new locking feature prevents people from forcing pharmaceuticals into an already full box. Nobody will walk off with this one either. It’s bolted to the ground.

Medicine take-back programs help prevent these chemicals from being flushed or thrown in the trash, potentially contaminating local waterways. Taking in unwanted medicines is a public safety issue too.

“If we can take it here in this box, it means they’re not in somebody’s grasp at home—toddlers take anything they can grab,” said Amy Anderson, Urbana animal control officer/community liaison, who manages the box.

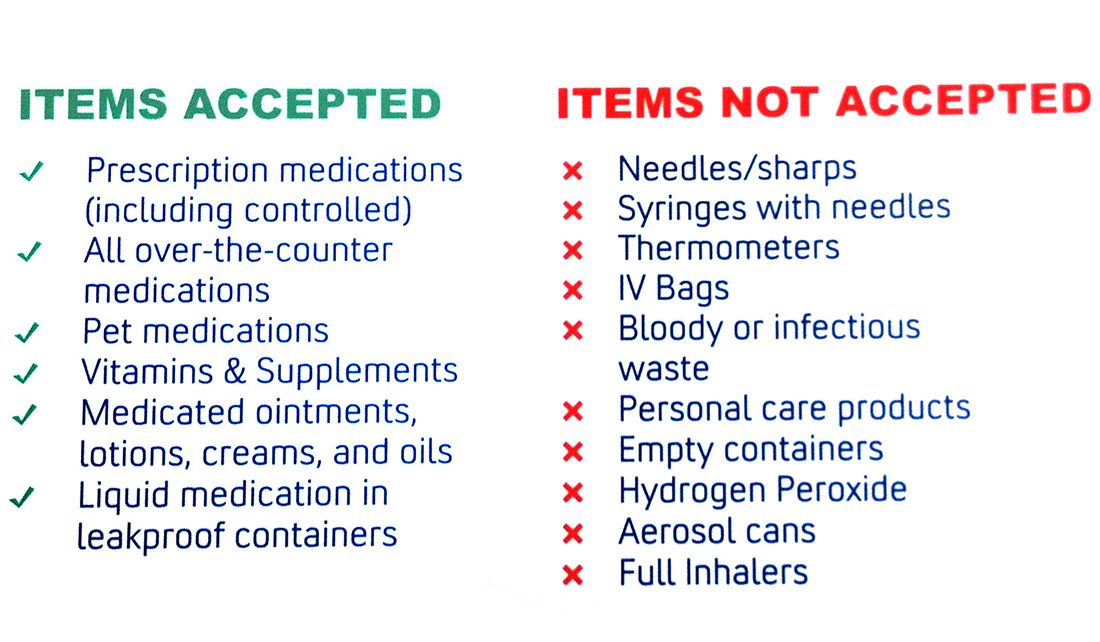

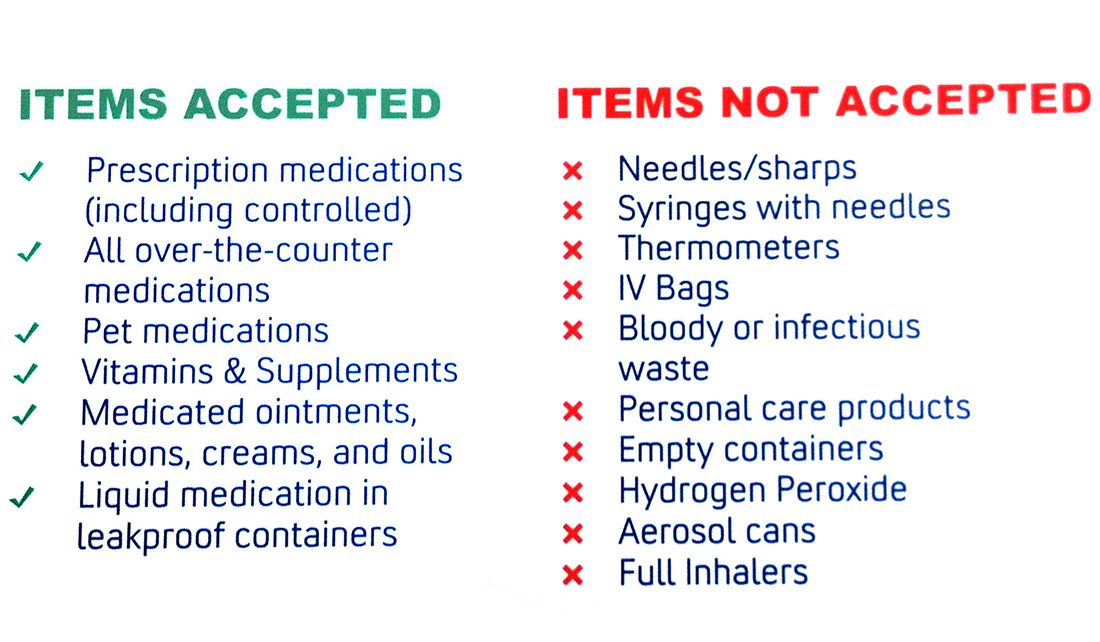

The police department, along with more than 50 locations in four states—including one in Champaign and one at the university—are designated to accept prescription and over-the-counter medicines, including veterinary pharmaceuticals, but not illicit drugs, syringes, needles or thermometers. IISG provides each location with the drug collection box and works with community partners to ensure the program’s success. All collected drugs are incinerated—the environmentally preferred disposal method.

The Champaign and Urbana medicine take-back programs started in 2013 and have collected more than 13,000 pounds of medicine. The IISG take-back program as a whole, which was established in 2007, has collected more than 58 tons. In addition, Sea Grant has helped collect over 30 tons just from helping out in single-day events throughout the Great Lakes region.

Amy Anderson, Urbana animal control officer/community liaison, (left) and Lieutenant Robert Fitzgerald pose with the new medicine take-back box in the lobby of the Urbana Police Department.

“The partnership we have with the Urbana Police Department, Champaign Police Department, and University of Illinois Police Department is so valuable,” said Sarah Zack, IISG pollution prevention extension specialist. “They do a great public service by operating this take-back program, and I hope that people can take advantage of the convenient drop-off locations in the C-U area.”

Be sure to visit unwantedmeds.org to find your local take-back location.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

April 25th, 2016 by IISG

Do you have expired or unused medicine sitting around your house? How you choose to get rid of those drugs could hurt our waterways.

“Research has shown that there can be negative effects to animal health and reproduction from pharmaceuticals that haven’t been removed from wastewater,” said Sarah Zack, the pollution prevention extension specialist for Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant. “Wastewater treatment plants weren’t designed to remove many of the compounds getting into them.”

So, how should you get rid of your drugs? Instead of putting medicines in the trash or flushing them in the toilet, bring them to National Prescription Drug Take-Back Day 10 a.m.-2 p.m. April 30. There are 310 sites in Illinois and 135 sites in Indiana. The day is being hosted by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, and people can find the nearest drop off location on the DEA’s website.

There is a large and growing body of research available about the environmental impacts of pharmaceuticals in waterways, but any potential long-term human health impacts are not yet clear. So in the meantime, making sure we properly dispose of unwanted medications is a good bet.

“There are other reasons besides just water quality for making sure that your medicines are disposed of properly,” Zack said, adding that pets and children can get into unused medicines around the house.

Besides taking medicine to take back programs, Zack said people should make sure they’re communicating with their physicians about getting the appropriate quantities of medicine.

“Don’t take a 90-day supply of a medicine if a 30-day supply is sufficient,” Zack said.

Being cognizant of what’s in your medicine cabinet and being willing to say “no,” to samples of medication you don’t need are other ways to decrease the amount of prescription drugs you own.

More than 5.5 million pounds of pills have been collected since the event was created in 2010, according to the DEA’s website. Pills and patches may be dropped off, but the program cannot accept liquids or needles or sharps. The day is free and anonymous.

“It’s really important that we have these events to give the public an opportunity to ensure that they are being responsible with medicines,” Zack said.

If you are interested in setting up a permanent medicine disposal site in your local police station, contact Sarah Zack. You can also reach here on Twitter:.

Ali Braboy is a senior studying journalism at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

November 11th, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

After the third or fourth hour working on a paper, the practiced and true route of an English major like myself is to pop an Advil to quell the emerging headache and drink a few cups of coffee to keep writing. Now, as an intern at Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG), I am learning that along with a perfectly finished paper, I am inadvertently creating a harmful effect in a body of water quite near us. The drugs we put in our bodies end up in other places in addition to juicing our creativity–some end up flushed into Lake Michigan, along with other bodies of water. In 2010, IISG funded a study in which scientists took samples from Lake Michigan and found an interesting presence of drugs and chemicals that did not belong in the water.

Our bodies do not effectively digest the drugs that we ingest and, as a result, we excrete and flush them down the toilet. Then, the wastewater treatment plants do not always effectively remove the drugs and their by-products.

Wastewater treatment plants are designed to effectively filter used water and send it back into lakes and streams, but Lake Michigan, along with other water bodies, has been receiving outpourings of various medicines and personal care products, and into its clear waters for years. Studies done in 2013 found that only a few of the drugs that are flushed away are treated by wastewater treatment plants; the rest wind up undissolved in Lake Michigan where they remain, due to the fact that the active pharmaceutical ingredients remain intact. Researchers have found drugs as far as two miles away from sewage plants, suggesting that the lake was not diluting the compounds.

Why are these treatment plants, which have been designed specifically to filter wastewater, not effectively targeting and getting rid of the medicinal pollutants before they hit the sunny, boat populated shores of Lake Michigan? The unfortunate fact is that the treatment facilities were designed with other priorities in mind, and their technology is not always up to date. While the plants are effectively filtering out the trash and waste that was always evident in wastewater, only some drugs are being filtered out.

Drugs that are found in wastewater include commonly used medicines and hormones such as caffeine, acetaminophen, and estriol. They do not cause a disastrous problem though, due to their easy break down. On the other hand, many antibacterial compounds, found in soaps, toothpastes, antibiotics, and anti-inflammatory drugs, do not dissolve as easily. These compounds may cause issues for both the wildlife and humans who come into contact with the water.

There have been some effects of the water’s contamination measured in the lake’s wildlife. For example, studies show that a certain type of diabetes medication found in Lake Michigan has been affecting the hormonal system of fish that are exposed to it. To be specific, the Type 2 diabetes medication, Metformin, is disrupting male fathead minnows’ endocrine systems and thus affecting their procreation with female minnows. Other changes that wildlife are enduring are still under observation.

Wildlife in the water has constant exposure to this pollution. On the other hand, humans will not see immediate impacts but rather long-term changes, depending on each individual’s contact with the polluted water.

As of now, Lake Michigan’s water has not yet been proven to dangerously affect humans. The doses of each medicine are low in the great, large body of water. And there is no data that shows what effect such low doses have on people who may accidentally ingest the water when swimming in the lake, or whose cities may use the lake water as their water source. On the other hand, there is also such a large variety of medicines and personal care products in the water that the intermingling may prove a threat to our health down the road. However, the World Health Organization and the Environmental Protection Agency conclude that no immediate threat is posed to humans.

The treatment plants do, in fact, remove large quantities of medication from the water; however, since many drugs are coming in such a constant manner, it becomes harder to target the pollutants at a 100 percent efficiency rate. The recent reports of 2013 demonstrate a correlation between Lake Michigan pollution, and society’s constant use of prescribed medicines. Because many people are ingesting more drugs, more drug compounds end up in the water. People are also not familiar with the correct and environmentally efficient way to get rid of unwanted drugs. Many people naively flush the remnants down the toilet and flush their responsibility away with the drugs. But for the lake and its inhabitants, the issues are only beginning.

-Olivia Widalski, IISG intern

This is the first article in the series Lake Lessons written by Olivia about the issues surrounding pharmaceutical pollution and disposal.

November 6th, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

This story starts with a nursing student named Sara. Adrienne Gulley, my pollution prevention colleague (pictured speaking with a conference attendee), and I met Sara while overseeing the IISG exhibitor booth at the American Public Health Association (APHA) annual meeting. We had been there two days and had already talked to about 1,200 public health professionals and students.

Some of the conversations were eye-opening. A few of our booth visitors admitted that they didn’t know that flushing medicine down the toilet was not the way to properly dispose of it. Other interactions were downright refreshing—which brings us back to Sara.

Sara and two other students stopped by our table for the pill-shaped USB drives, but they stayed to learn about how to properly dispose of expired and unwanted medication. Then they stayed a little longer to learn how to read ingredient labels to see if their personal care products contain plastic microbeads. They were engaged and polite, just like every other person that stopped to talk with us.

But unlike every other person, five minutes after Sara left our table, she came back. And she brought more students with her. Before Adrienne or I even had time to say hello, Sara was explaining what microbeads are, what to look for on the ingredient list (polyethylene or polypropylene), and that microbeads have been found in several species of fish in the Great Lakes.

Over the course of the four-day event, we talked to people from at least 23 states as well as Puerto Rico, Uganda, South Africa, and Afghanistan—sharing information and learning some new things ourselves. But Sara is going to stick in my mind for a long time.

Sara, if you are reading this, if the nursing career doesn’t work out, I think you have a very strong future in education and outreach.

November 5th, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

A new version of the award-winning curriculum The Medicine Chest is now available! This updated and revised version includes new lessons and new teaching approaches. Here’s the story of how this edition came to be.

In 2012, I started in a new position at the University of Illinois and was introduced to the issue of pharmaceuticals and personal care product (PPCP) pollution. I thought it was fascinating and realized that past instructions to flush medicine down the toilet probably weren’t based on research.

I was interested even then in developing a curriculum on this emerging issue, but it wasn’t until I joined IISG that an opportunity materialized. It was then that I came to learn about the compendium of lessons known as The Medicine Chest that includes wonderful place-based stewardship lessons. I felt I could enhance the content by emphasizing the “Why should I care?” factor. I was asked that exact question by suburban high school student about 10 years ago while teaching a lesson on isotopes. It was the best question I ever received. And from that point on, all the materials I have created have been based on that pivotal query.

For The Medicine Chest, I wanted to approach the issue from a number of different perspectives. The updated curriculum connects ideas that aren’t really thought of as connected. For instance, nobody really thinks about items that are flushed down the toilet after the handle has been pushed, so why not explore wastewater treatment plants to see what they can filter and what products pass through the system and out to waterways? The lesson named “Wastewater treatment 101: What happens to PPCPs?” does just that. I have also created a lesson using recent research on how PPCPs are changing the normal functionality of aquatic ecosystems. Once the problems are laid out, the curriculum moves on to show how individuals can help reduce the impacts of PPCPs. Finally, as sort of an interesting twist, we look back into the not-so-distant past—turn of the 20th century—to see what kinds of products were used to cure illness and create beauty and how they compare to today’s standards.

I decided to incorporate new teaching techniques into the curriculum. First, the curriculum gives teachers the option to teach each lesson in the conventional way—information gathered in class and followed up by homework—or through a technique called “flipped classrooms.” This model asks students to learn the information, with guidance, the night before and be ready to discuss the topic in class for more in-depth exploration. Second, I applied meta-cognitive thinking to the vocabulary. Third, I abandoned the standard method of testing in favor of essay responses. This technique pairs well with metacognitive thinking and true knowledge because it allows students to express in their own words what they know about the questions being asked. Finally, I aligned the lessons with the Next Generation Science Standards. These new lessons can all be used to lead into the many stewardship-based projects already provided in The Medicine Chest.

One of the challenging aspects of writing curriculum on any emerging topic is that the research is still very new and ever evolving. Once the research is located, many times there are gaps of information about the issue. Then, of course, you have to make the information accessible to different audiences. That is often the most challenging aspect of the work, but it’s all worth it. It’s pleasure to write about emerging issues, and I already have my sights on another topic. I’m excited for the possibilities.

June 16th, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

By Anne Packard (Anne is a summer intern working with Laura Kammin, IISG pollution prevention specialist)

Can pharmacists play a role in pollution control? This is the question I asked myself when I heard about an internship through Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant.

Can pharmacists play a role in pollution control? This is the question I asked myself when I heard about an internship through Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant.

As a third year student at Purdue University College of Pharmacy, I became interested in this internship because of my love for the Great Lakes. I am a western Michigan native, so the freshwater lakes are dear to my heart. At a young age, I took advantage of all the benefits living close to Lake Michigan can provide. I have fond memories of sailing, watching the sunset, and building sand castles on the beach.

During the school year, being a pharmacy student feels like a 24 hour a day job. The amount of time spent studying and thinking about pharmacy related topics is quite demanding. I have to love what I study. The pollution prevention internship is a great way for me integrate two key facets of my life—my pharmaceutical knowledge and my love of the environment and the Great Lakes.

My role with Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is to help with education in the community with regards to medication pollution and disposal. Another major aspect that ties in my pharmacy experience will be to educate people about the consequences for misuse, accidental poisonings and abuse of unused medication. I also am working with a Purdue College of Pharmacy professor to organize data to better understand the needs in the Lafayette area related to medication take back programs.

Even in the few weeks since starting, my knowledge base on medication pollution has expanded substantially. By the end of this summer I hope to take the knowledge I have gained and apply it in my future career as a pharmacist. Through this experience I want to be knowledgeable about the resources available for proper medication disposal as well as tools to implement safe disposal practices wherever my career takes me.

As with all student interns, there is always a dream of making a difference in the job they are in. Although, I do not expect to make groundbreaking changes, I hope I can help my community take a step in the right direction to minimize pharmaceutical pollution in the environment.

March 19th, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

Allison Neubauer and Kirsten Walker were at the University of Illinois Public Engagement Symposium last week to raise awareness of IISG outreach in Champaign-Urbana. Allison had this to say about the event.

The public engagement symposium was a great opportunity to find out what other local organizations and academic programs are working on. The crowds of people—both those staffing booths and walking through and exploring—were a true testament to Champaign-Urbana’s widespread effort to get involved and take collective action on local initiatives.

Our IISG table generated a lot of traffic. With spring on the horizon, many visitors were excited to learn about our mobile walking tour of downtown Chicago. Others stopped to discuss invasive species and ways they can help halt their spread.

But the biggest draw was our university Learning in Community (LINC) course poster, created by undergraduate students enrolled in our section last fall. These students focused on increasing awareness on campus about how pharmaceuticals contaminate our waterways. They also coordinated a take-back event for students and community members to properly dispose of their unwanted medication. The event was a big success, collecting 15 pounds of unused medicine for incineration in just six hours.

But the biggest draw was our university Learning in Community (LINC) course poster, created by undergraduate students enrolled in our section last fall. These students focused on increasing awareness on campus about how pharmaceuticals contaminate our waterways. They also coordinated a take-back event for students and community members to properly dispose of their unwanted medication. The event was a big success, collecting 15 pounds of unused medicine for incineration in just six hours.

For Kirsten and I, what was particularly exciting and unique about this symposium was our ability to connect with others working locally on related problems. For example, a Champaign community health center invited us to discuss pharmaceutical disposal with their patients. There was also a UIUC engineering student interested in the homemade filtration system our LINC students created with local high schoolers to show how some contaminants can slip through wastewater treatment processes. She is currently working to design and implement a water system and health program in a rural Honduran community and was looking for ways to engage with local residents.

March 9th, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

Community medicine collection programs make it easy for people to rid their homes of unwanted pharmaceuticals, but they can be difficult to get off the ground. That’s where our Unwanted Meds team comes in. They have helped police departments across Illinois and Indiana establish collection programs and raise awareness of the importance of proper disposal.

Community medicine collection programs make it easy for people to rid their homes of unwanted pharmaceuticals, but they can be difficult to get off the ground. That’s where our Unwanted Meds team comes in. They have helped police departments across Illinois and Indiana establish collection programs and raise awareness of the importance of proper disposal.

From Rx for Action:

In today’s Community Spotlight feature, we look at West Lafayette Police Department’s Prescription/Over-the-Counter Drug Take Back (Rx/OTC) program. In 2010, Officer Janet Winslow started the wildly successful take-back program, one that has no doubt had a dramatic impact on the community and the environment.

Officer Winslow took a little time out of her busy schedule to answer a few questions for us about the take-back program. And if the work she does here isn’t enough to show what an asset to the community she is, she has also just been named a YWCA Greater Lafayette Woman of Distinction, and will be honored at the “Salute to Women” banquet. Congratulations Officer Winslow!

1. The West Lafayette Police Department collection program started in March 2010. How did this program come about for your area, and why did you decide to take part?

DARE America sent out a request for DARE officers to provide the community with a presentation on Rx/OTC medicines and do a take-back at the same time. I did a community presentation and actually had more people bring me Rx/OTC to be destroyed then that came to the presentation. Since that was successful I asked my Chief if I could try to do it monthly to see how the turnout would be. The “go greener” commission had also expressed and interest to the city government to attempt a take-back.

2. What has been the community’s response? What are people saying about the medicine take-back opportunities and the program?

I do the take-back monthly and every month I think it will be less. I literally have people standing in the police department lobby waiting for me to get my table and boxes set up. It has grown from one small box (~25 pounds) to 6-12 boxes, sometimes over 200 pounds every month. A lot of the people who use my program thank me for providing it to the community.

3. A lot of take-back programs have permanent collection boxes at police departments, but you plan, set-up, collect, and run the entire program (monthly events) yourself. What are some benefits of running a program in this manner?

My chief has asked me several times about getting the permanent box. My answer is always the same: I do not have time daily to check the box. I do not want liquids spilled in the box or broken bottles. Due to a lack of space I started separating the pills from the bottles. I do this as I am taking them back. I then recycle the bottles and the lids are delivered to an organization that makes park benches. I also like the interaction I have with the community during the take-backs.

December 15th, 2014 by iisg_superadmin

University of Illinois students and faculty took a break from the end-of-semester chaos earlier this month to take advantage of a single-day medicine take-back. The student-led event was part of the Learning in Community (LINC) service course facilitated by IISG.

“We spoke to so many different people to put on this event, from police officers to student organization leaders on campus to Jimmy John’s representatives,” said Reema Abi-Akar, a senior in urban planning. “We looked into case studies of past medicine take-back events, learned the ropes, and slowly absorbed all of the components we needed to replicate to put on a successful event.”

“Preparations for the event were challenging,” added Rosalee Celis, project manager and senior in biomedical engineering. “There were various marketing aspects that still had to be completed and communication between a 10-member team over Thanksgiving break was difficult. However, the efforts exerted during this crunch time made the results more satisfying.”

The event was a success, collecting 15 pounds of unused medicine for incineration in just six hours.

This was just one of the outreach projects led by the LINC students this year. The class, which includes eight students and two undergraduate project managers, also gave an interactive presentation to an ESL class at Urbana High School to raise awareness of the risks of pharmaceutical pollution and the importance of proper disposal.

This was just one of the outreach projects led by the LINC students this year. The class, which includes eight students and two undergraduate project managers, also gave an interactive presentation to an ESL class at Urbana High School to raise awareness of the risks of pharmaceutical pollution and the importance of proper disposal.

“Our group truly feels like we made a difference in the community and spread the word about proper medicine disposal,” Reema said.

And the course has been an eye-opening experience for the students as well.

“To be honest, I started this experience with little to no knowledge about proper medicine disposal,” Reema continued. “All the old medications in my parents’ medicine cabinet were simply collecting dust for years because we never knew how to get rid of them. Once I came into this LINC class and my group began researching the subject further, I became more and more interested in it—and I believe I’m speaking for my entire group as well.

“I can now enter the professional workforce in the pharmaceutical industry with the awareness of potential environmental damage due to pharmaceutical waste,” said Rosalee.