June 17th, 2019 by IISG

The Great Lakes Legacy Act team that successfully remediated the wetlands below the former Zephyr Oil Refinery in Michigan won the Western Dredging Association (WEDA) 2019 Environmental Excellence Award. During its Annual Summit & Expo in Chicago, held from June 4-7, WEDA presented two Environmental Excellence Awards, recognizing projects that demonstrate environmental awareness in each of two categories. The “Environmental Dredging” award went to the Zephyr Refinery Project and the “Mitigation and Adaptation to Climate Change” award to the La Quinta Aquatic Habitat Mitigation Project.

The prize winners fulfilled and exceeded the criteria of the Environmental Commission and made outstanding contributions to meeting the goals of WEDA, which are to “promote communication and understanding of environmental issues and stimulate new solutions associated with dredging and placement of dredged materials such that dredging projects, including navigation and environmental, are accomplished in an efficient manner while meeting environmental goals.”

The 2019 WEDA Environmental Excellence Award for Environmental Dredging was presented to the project team from EA Engineering, Science, and Technology, Inc., PBC (EA) and Sevenson Environmental Services (SES) for the dredging and restoration of the Former Zephyr Refinery: Fire Suppression Ditch project (Zephyr project). Other entities accepting the award included project owners the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Great Lakes National Program Office (GLNPO) and the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ), as well as project partners Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, the West Michigan Shoreline Regional Development Commission, and the Muskegon Lake Watershed Partnership.

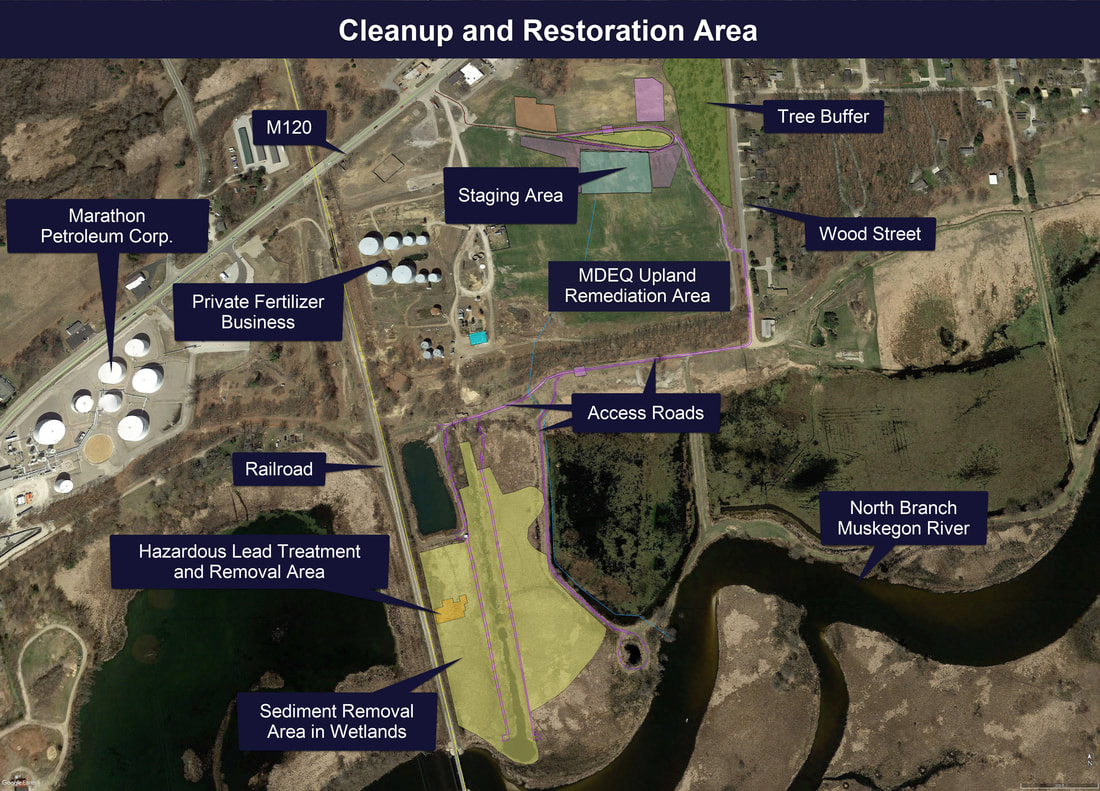

The Zephyr project area is located along the North Branch of the Muskegon River in the Muskegon Lake Area of Concern (AOC), Muskegon, Michigan. For more than 40 years, the Zephyr Oil Refinery operated with historic releases of petroleum and metals into the Muskegon Lake watershed. These releases contributed to significant contamination of the sediment and wetlands surrounding the site and resulted in the loss of fish and wildlife habitat, as well as other beneficial use impairments (BUIs) to the AOC. The Zephyr project was identified in the Stage 2 Remedial Action Plan for the Muskegon Lake AOC for restoration in order to support BUI removal. Under the Great Lakes Legacy Act, through the strong partnership between the U.S. EPA GLNPO and MDEQ, the project was completed in late 2018.

The Zephyr project area is located along the North Branch of the Muskegon River in the Muskegon Lake Area of Concern (AOC), Muskegon, Michigan. For more than 40 years, the Zephyr Oil Refinery operated with historic releases of petroleum and metals into the Muskegon Lake watershed. These releases contributed to significant contamination of the sediment and wetlands surrounding the site and resulted in the loss of fish and wildlife habitat, as well as other beneficial use impairments (BUIs) to the AOC. The Zephyr project was identified in the Stage 2 Remedial Action Plan for the Muskegon Lake AOC for restoration in order to support BUI removal. Under the Great Lakes Legacy Act, through the strong partnership between the U.S. EPA GLNPO and MDEQ, the project was completed in late 2018.

In addition to receiving the Environmental Excellence Award, the U.S. EPA GLNPO accepted WEDA’s Special Recognition Award for accomplishments toward restoring and protecting the health of the Great Lakes, specifically by remediating historical contamination in ports, harbors and other waterways. The people at GLNPO were honored as key players and leaders in finding practicable solutions to complex problems, just as they had in the remediation of the wetlands near the former Zephyr Oil Refinery.

The Zephyr project provided numerous environmental benefits by remediating legacy contamination and restoring native habitat within a Great Lakes AOC, and contributing to the future removal of BUIs within the AOC. It demonstrated how innovative partnerships and contracting approaches can lead to success on many levels. The remediation will provide economic benefits to the Muskegon Lake area and Great Lakes region and the many lessons learned will be beneficial for future projects. In addition, the thorough public outreach activities – the site is located adjacent to residential areas – demonstrated the importance of engaging with residents and other concerned citizens.

“Community outreach was a priority and a team effort at Zephyr,” said Caitie Nigrelli, environmental social scientist with the U.S. EPA and Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant. “We were digging up petroleum-based contaminants upwind of a neighborhood. We wanted to be a good neighbor. We needed to know that our project was maintaining air quality standards, and had a plan in place to communicate that. We went door to door before construction started to alert neighbors of potential odors and thank them in advance for their patience.”

“Community outreach was a priority and a team effort at Zephyr,” said Caitie Nigrelli, environmental social scientist with the U.S. EPA and Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant. “We were digging up petroleum-based contaminants upwind of a neighborhood. We wanted to be a good neighbor. We needed to know that our project was maintaining air quality standards, and had a plan in place to communicate that. We went door to door before construction started to alert neighbors of potential odors and thank them in advance for their patience.”

Sustainable approaches were implemented in the remediation, including the reuse of all woody debris and trees removed on the site for habitat structures. The project team also left approximately 8% of the haul road material in place for an upcoming restoration project on the adjacent property, therefore reducing disposal quantities and reusing material in a beneficial manner. Finally, the environmental dredging of the Former Zephyr Refinery: Fire Suppression Ditch area included many unique elements that will be transferable and adaptable to future contaminated sediment remediation and restoration projects with similar characteristics.

To learn more about the Zephyr remediation process and to see drone footage of the wetlands before and after cleanup, visit Great Lakes Mud.

For further information, contact:

Thomas P. Cappellino, WEDA Executive Director

Craig Vogt, Ocean and Coastal Environmental Consulting

January 24th, 2017 by IISG

“It was an early morning start with sampling near Stony Point along the northern shores of Minnesota,” Ann Quinn, of Pennsylvania and Krysta Maas, of Minnesota, wrote in a blog post in July of 2016.

“As we approached Duluth, we stopped three times to sample near the shore and within the harbor. As we passed under the lift bridge, we could ‘clearly see’ the sediment plume from Monday night’s tremendous storm.”

Quinn and Maas were two of the 15 educators chosen last year to participate in the annual Shipboard Science Workshop aboard the U.S. EPA’s largest research and monitoring vessel on the Great Lakes, R/V Lake Guardian. Sea Grant’s Center for Great Lakes Literacy (CGLL) with U.S. EPA Great Lakes National Program Office (GLNPO) host the annual program. CGLL, formerly known of Centers for Ocean Science and Educational Exploration, is a collaborative effort led by Sea Grant educators throughout the Great Lakes watershed. This cruise is an important cornerstone of CGLL’s programming.

Every summer since 2006, CGLL joins forces with GLNPO to facilitate this weeklong workshop on one of the Great Lakes. Educators from not only traditional classrooms but also from places like museums, zoos and nature centers are welcome. The experience provides educators in the Great Lakes basin the opportunity to actually “do” science alongside aquatic researchers and learn strategies to integrate Great Lakes science into their curriculum.

IISG community outreach specialist Kristin TePas, who as the Sea Grant liaison with GLNPO accompanies every cruise, never tires of seeing teachers learning and researching in the field.

“I always look forward to watching how the educators take to the whole experience,” TePas said. “They come on rather green and leave at the end of the week looking like they have always lived on the ship, working like a well-oiled machine, taking part in field sampling and then analyzing in the lab.”

The hands-on, immersive nature of the experience fosters a broader and deeper understanding of science by integrating knowledge and research to enhance the teachers’ scientific investigation skills. Educators also expand their “treasure box” of lessons, teaching strategies, and network of like-minded colleagues.

Following their time aboard the R/V Lake Guardian, the teachers return to their classroom with newfound knowledge that they then implement into school initiatives, like organizing cleanups of nearby natural areas, starting real-world data collection and analysis for class projects, bringing scientists into the classroom to talk and work with students, and inspiring school science and environmental clubs.

Alex Valencic, an alumnus of the 2013 Lake Ontario cruise, incorporated his experience into his fourth-grade class in Illinois.

Each student spent six weeks studying a freshwater fish found in the Great Lakes and learned about its appearance, habitat, life cycle, and where it falls in the food web.

“My primary goal is for my students to understand the rich diversity of life that lives within the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Seaway,” he said. “Even though we don’t live right on a lake, Illinois is hugely impacted by Lake Michigan.”

Educators and scientists on recent cruises have taken advantage of a new way to communicate their experiences to those back on land. In addition to filing blog posts on the CGLL website, folks on the cruise have started using Twitter to document their journey while traversing the lake. Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant Educator Allison Neubauer has compiled the tweets into a narrative of the cruise.

“Showing off the collaboration as it’s happening, making it accessible and informative,” Neubauer said, “is a great way to tell the important story of the work being done by the teachers and researchers in only seven days.”

The scientists onboard were equally impressed with the experience.

“A strong scientist-educator connection can bring the research alive as scientists share stories from the field or lab,” wrote Wisconsin researcher Emily Tyner in “Scientist Spotlights,” an ongoing series on the CGLL website.

“But the sharing process isn’t one-way,” Tyner pointed out. “Educators can offer a new and helpful way of looking at problems that stump scientists. Thinking back on my Lake Guardian cruise, the educators helped us gain helpful perspective when we faced hours trying to determine the problems with our experimental setup.”

The educators no doubt would agree. They get the chance—as many have put it—to take part in an adventurous, educational, inspiring, fun, and once-in-a-lifetime adventure!

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

January 13th, 2017 by IISG

For the month of January, the Sea Grant 50th is focusing on K to Gray education—yes, that includes everyone—and within IISG there is no shortage of resources for all ages.

Terri Hallesy who has been with the IISG education team for 13 years has seen teaching trends change over the years, but in the end, she knows it’s really very simple.

“I just enjoy working with all the dynamic, engaging specialists,” Hallesy says. “They each focus on diverse programs and target different audiences. What’s great is they’re always ready to collaborate using the latest and most relevant educational tools.”

Below we are highlighting five of the projects the education team has produced—in collaboration with specialists, other Sea Grants, as well as educators—that capture that cooperative spirit.

Nab the Aquatic Invader!

Nab the Aquatic Invader!

Launched in 2009, this website focuses on the suspects–aka the invasive species–in four regions of the country: Atlantic, Pacific, Gulf, and Great Lakes. In each region, visitors can see read interrogation interviews with the 10 Most Wanted AIS and learn their origin, problems they cause, and some control methods used to slow the spread of these species. The project was featured in the Smithsonian in 2010.

Collaborators included New York, Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Ohio Sea Grants.

The Medicine Chest

The Medicine Chest

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant’s (IISG), The Medicine Chest, invites high school students to metaphorically open up those doors and investigate what makes those chemicals harmful to people, pets, and the environment when improperly disposed. The curriculum was updated last year.

Collaborators included Pennsylvania Sea Grant, U.S. EPA Great Lakes National Program Office, and Paul Ritter and Eric Bohm, P2D2 Program Administrators.

Sensible Disposal of Unwanted Medicines

When medications are flushed down the toilet, wastewater treatment plants can’t always filter out the harmful chemicals that can affect wildlife and even get into drinking water supplies. This 4-H guidebook and curriculum, designed for informal education audiences, provides five inquiry-based lessons to help high school youth understand the harmful effects of improper disposal of medicines and what they can do to help.

Collaborators included 4-H and Penn High School, Mishawaka, Indiana.

Fresh and Salt

Fresh and Salt

Fresh and Salt is a collection of activities that enhance teacher capabilities to connect Great Lakes and ocean science topics. Designed to be used by teachers in grades 5-10, this curriculum provides an interdisciplinary approach to ensure that students achieve optimum science understanding of both Great Lakes and Ocean Literacy Principles.

Collaborators included Centers for Ocean Science Education Excellence and Ashland University.

Lake Michigan by the Numbers

Lake Michigan by the Numbers

This curriculum was created by teachers who attended a day-long workshop to learn how to incorporate buoy data into their classroom instruction. They created these data-rich, STEM-based lesson plans that boost understanding of Great Lakes issues by incorporating real-time data from Great Lakes buoys.

Collaborators included Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Lake Michigan Coastal Program, and Center for Great Lakes Literacy.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

November 11th, 2016 by IISG

This post, written by Kathryn Meyer and Todd Nettesheim, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, originally appeared on the International Joint Commission website.

Out on the Great Lakes, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Lake Guardian research vessel is not your typical ship.

It has the usual pilot house, cabin rooms, and galley, but this 180-foot research vessel has a few extra special features. Those include three onboard laboratories; a Rosette water sampler for measuring conductivity, temperature and depth; and multiple devices for sediment collection. These additions allow researchers to analyze water, sediment, and biological data while the Lake Guardian travels across the Great Lakes.

Also special is the collaborative group of scientists, from the U.S. EPA’s Great Lakes National Program Office (GLNPO) and other government agencies and universities, working onboard to collect and analyze samples to monitor the health of the Great Lakes. The overarching goal of the science performed onboard is to understand the chemical, physical, and biological changes in the lakes to help inform fishery and water quality managers.

The Lake Guardian is a floating laboratory essential to many Great Lakes long-term monitoring programs, with about 25 years of data collected since its first voyage on the lakes in 1991. Starting out on Lake Michigan, the ship samples the lakes twice a year as part of the routine spring and summer surveys. The ship weaves across each lake to reach specified sampling stations. Onboard, scientists and crew work around the clock to ensure that each station is sampled as the ship passes by Great Lakes icons including the Mackinac Bridge, Welland Canal, Soo Locks, and Isle Royale.

Other parts of the Great Lakes are sampled by the EPA’s research vessel Mudpuppy II, a 33-foot shallow vessel designed for studies to determine the nature and extent of contaminated sediment in Great Lakes nearshore areas.

In August, EPA scientists from GLNPO collaborated with scientists from Buffalo State, Cornell University, University of Chicago, and University of Minnesota-Duluth to complete the Lake Guardian’s 2016 Summer Survey.

The survey consists of 97 stations where scientists collect water, phytoplankton, zooplankton, benthos (invertebrates that live on the bottom of the lakes), and sediment samples. Each station starts with the Rosette sampler plunging into the water to retrieve water samples at different depths on the starboard side, while on the aft deck plankton nets are cast into the water.

On some stations, a ponar sampler also is dropped to the bottom of the lake to scoop up sediment and collect benthos. Once the samples are back onboard, they are either immediately analyzed in one of the ship’s labs or preserved for analysis on land. The water samples help to track nutrient concentrations among other water chemistry parameters. The biological samples help us track changes and better understand the lower food web in the lakes.

The month of sample collection and analysis, knowledge-sharing and comradery onboard the Lake Guardian highlights the shared commitment to protect the health of the Great Lakes.

For example, GLNPO began monitoring nutrient concentrations in Lake Erie in 1983 to assess the effectiveness of phosphorus load reduction programs initiated by the 1983 phosphorus load supplement to the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA). Data showed that the lake responded to the phosphorus load reductions and in-lake total phosphorus concentrations approached targets in the late 1980s. Our data also documented the re-eutrophication of Lake Erie that began in the early 1990s.

When the ship is not completing one of the long-term annual spring and summer surveys, the vessel supports additional monitoring efforts across the lakes. These include monitoring dissolved oxygen levels in Lake Erie and supporting collaborative science as part of the Cooperative Science and Monitoring Initiative (CSMI) – a binational program established under the GLWQA. The US EPA and Environment and Climate Change Canada work with a broad array of partners to implement CSMI in fulfillment of GLWQA requirements.

This year, CSMI was focused in Lake Superior, where more than 200 water samples, 150 plankton nets, and 600 ponar grabs were performed across the lake to assess the long-term status of the lower food web. Each year, the Lake Guardian also serves as a floating classroom for educators throughout the Great Lakes thanks to programs run by the Center for Great Lakes Literacy.

Interested in learning more about the R/V Lake Guardian? Check out the EPA Great Lakes website. You can also check out information from one of our partners, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, and the Lake Guardian Twitter page to stay up-to-date and see if she’s coming to a port near you.

Editor’s Note: There are 78 science vessels active in the Great Lakes, each more than 25 feet long, and smaller boats which assist conservation officers, scientists, educators and resource managers (See this interactive map). Over the years, these operators have formed the Great Lakes Association of Science Ships (GLASS), with 68 American and Canadian participating organizations networking and providing information about these vessels at www.CanAmGlass.org.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

September 27th, 2016 by IISG

Caitie Nigrelli, IISG environmental social scientist, was recognized with two Bronze Medal Awards from U.S. EPA Region 5 for her work as part of the East Branch Grand Calumet River remediation and restoration project team and the Lincoln Park area and Milwaukee River Channel remediation and restoration project team.

To learn more about Nigrelli’s participation in these projects, check out past coverage of the Grand Calumet River and of Lincoln Park.

Region 5 of the EPA covers six states surrounding the Great Lakes: Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio. A full list of the teams is below.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

July 29th, 2016 by IISG

Listen to Kristin TePas’ radio interview with University of Illinois Extension’s Todd E. Gleason below.

Fifteen educators are once again on dry land recovering from a schedule just as packed as the Lake Guardian’s quarters. The 2016 Shipboard Science Workshop on Lake Superior aboard the U.S. EPA Great Lakes National Program Office research vessel wrapped up last week. The annual workshop was hosted by Center for Great Lake Literacy and led by Minnesota Sea Grant.

Using state-of-the-art sensors, the teachers, alongside four research scientists from Minnesota and U.S. EPA, took part in water sampling—all day and night—to evaluate the presence of zooplankton, aquatic invasive species, and water quality and nutrient differences over time.

Teachers working in the lab on the Lake Guardian.

The teachers analyzed the samples in on-board laboratories and presented their findings after the ship dropped anchor. But their work is just beginning. The teachers now have the task of inspiring their own students to become Great Lakes scientific explorers.

“So many of our labs we do in class, the students have to do an experiment that simulates what would happen in real life,” Ashlee Giordano a science teacher at Northfield Jr./Sr. High School in Wabash, Indiana. “It is meaningful, however, showing students what I did, and the data we collected would really hit home for them.”

This year’s cruise received some special attention from University of Illinois Extension’s radio personality Todd E. Gleason who interviewed IISG community outreach specialist and liaison to U.S. EPA Kristin TePas over the phone while she was still on the trip. The interview was aired on stations throughout Illinois.

“We really want them to be more comfortable with science and understanding the process of research,” TePas said.

This year the teachers hailed from seven Great Lakes states. Two were from Illinois and one from Indiana.

The exhaustive effort scientists go through was not lost on Cheryl Dudeck, a biology and human anatomy teacher at King College Prep High School in Chicago.

“I was surprised by how many people it takes to complete one week of research. I also was surprised to find out that the research happens 24/7 and how it changes with the weather conditions,” Dudeck said.

“I think that most people do not understand the importance and complexity of the Great Lakes.”

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension.

June 27th, 2016 by IISG

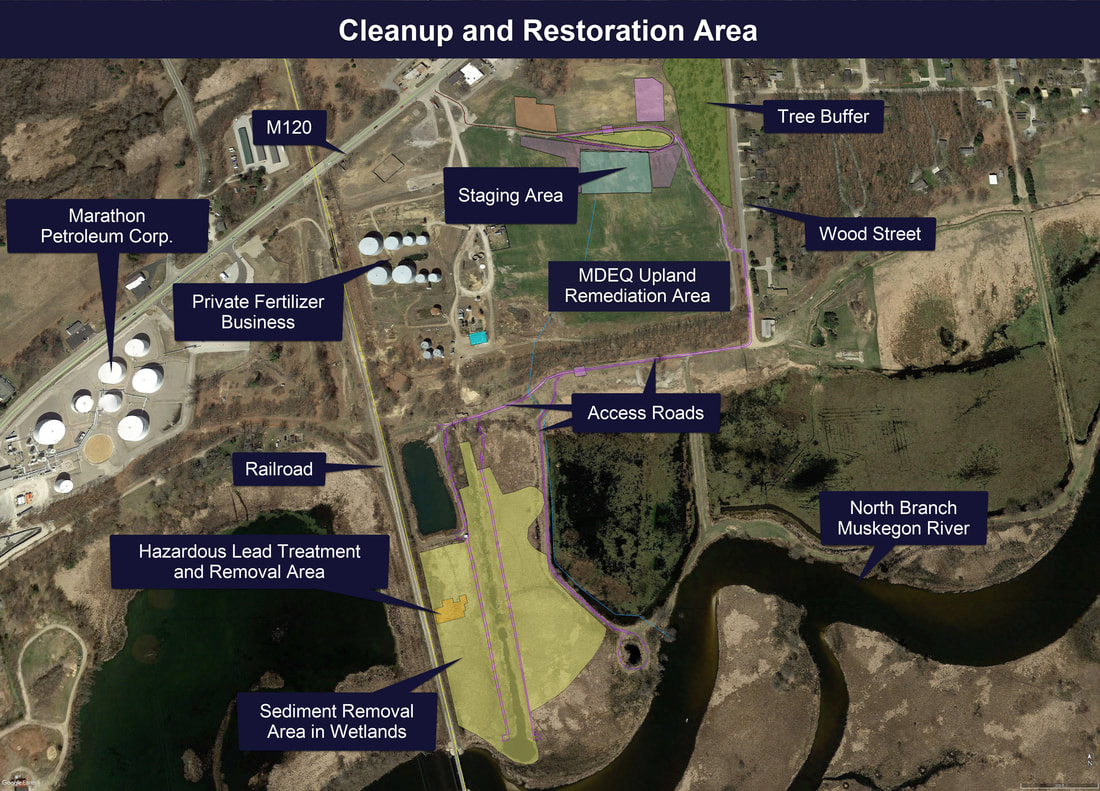

Last week, I joined U.S. EPA project managers from the Great Lakes National Program Office at the “Zephyr” site in Muskegon, Michigan (named for the Zephyr Oil Refinery that once existed on the property). Zephyr lies within the Muskegon Lake Area of Concern, a designation given because of the environmental degradation in its past. The EPA and the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) are about to begin a large-scale remediation to clean up the petroleum and lead pollution that remains in the sediment.

On my first day at the site, I was amazed to look south from the bluff to see what looked like a thriving, healthy wetland—albeit, a little overcrowded with cattails. It didn’t seem like the polluted site I’d read about, where petroleum fires were once a common occurrence or where lead concentrations are so high, remediated sediments will not be moved off site until they are treated.

While the south end of the Zephyr site, near the north branch of the Muskegon River looks picturesque, it still contains contaminants and is need of remediation.

But that’s the thing about legacy pollutants: They aren’t always as obvious as a bag of trash or a discarded television. Many contaminants are invisible to the naked eye. Even the visible ones can lie out of sight underwater and still pose a threat to the ecosystem, including the insects, fish, and birds that live there.

The remnants of petroleum are more apparent up close. In some locations at the Zephyr site, the water in the wetlands has an oily sheen to it. At others, there is a faint odor. Despite the issues, I was encouraged by discussions with MDEQ, EPA, and their contractors about the plan of work and project design. The Zephyr site is finally going to get cleaned up!

The work is being funded through a cost-share program between EPA and the State of Michigan under the Great Lakes Legacy Act. Unlike enforcement-style remediation programs, the Great Lakes Legacy Act encourages rapid remediation by offering cost sharing and avoiding blame. A project that could take decades of litigation can instead be completed in 3-5 years through cooperation. And it provides a mechanism to clean up contamination left behind by long-gone, bankrupted industries, as is the case at Zephyr.

An oily sheen near the Zephyr site.

From what I gleaned from the current property owner (who is not responsible for the pollution left behind by the former landowner) is that nearly everyone in the community is tired of the stigma associated with “the old Zephyr refinery.” And just because the remediation is happening entirely on private land doesn’t mean it won’t benefit the community. Sediment remediation will improve the quality of drinking water and reduce any odor or taste issues. Clean sediment will also provide better habitat for migratory fish and birds; a benefit to tourists and locals, alike.

An added benefit of a Great Lakes Legacy Act remediation project at the Zephyr site is the habitat restoration set to follow. The restoration design calls for open water habitats along with native wetland plants to provide ample habitat for waterfowl and other birds, amphibians, and reptiles while also improving the existing floodplain for the north branch of the Muskegon River.

U.S. EPA and Michigan DEQ officials take more sediment samples.

Remediation is tentatively planned for late fall 2016. Once a contractor is on board, equipment will brought to the site for what is called “mobilization.” Shortly afterwards, temporary roads will be constructed, a staging area will be established (to dry out the sediments before being transported off site), and excavation can commence.

My first Great Lakes Legacy Act site visit was very encouraging. Being on site with the project managers, partners, and engineers allowed me to see how a cooperative project functions. I was able to see the sediment up close and understand the concerns this community has had for decades. It’s obvious that a Great Lakes Legacy Act project, or any project of this magnitude, could not be completed alone.

Visit www.greatlakesmud.org for more information and updates on the project.

Ben Wegleitner is the new IISG social science outreach assistant supporting IISG Environmental Social Scientist Caitie Nigrelli.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

February 5th, 2015 by iisg_superadmin

Fisheries managers have long known that the population of rainbow smelt in the Great Lakes is on the decline. Once so abundant that they could be fished out with a pot or strainer, this important prey fish survives today in numbers hovering near historic lows. Numerous causes for the falling population have been proposed, but new research suggests that the population patterns and the forces driving them are more complicated than previously believed.

The 2014 study reveals that number of smelt that survive their first few months has actually been on the rise since 2000. But this increase in hatchlings isn’t translating into more adults, and it is unclear when and why that breakdown is happening. Whatever the cause, the loss of adult rainbow smelt is enough keep the population trending down even as offspring survival improves.

The 2014 study reveals that number of smelt that survive their first few months has actually been on the rise since 2000. But this increase in hatchlings isn’t translating into more adults, and it is unclear when and why that breakdown is happening. Whatever the cause, the loss of adult rainbow smelt is enough keep the population trending down even as offspring survival improves.

Researchers from USGS, IISG, Purdue University, and the U.S. EPA Great Lakes National Program Office, discovered the unexpected increase in offspring after analyzing roughly 40 years of fisheries data using a novel modeling technique.

Fish populations are typically analyzed using a statistical model that that assumes the relationships between different variables—things like number of offspring, number of adults, degree of predatory pressure, and amount of rainfall—remain the same over time. For this study, researchers used statistical tools rarely used by fishery scientists that better reflect the ever-changing nature of the Great Lakes and make it possible to detect more subtle population patterns.

Perhaps most surprising is that offspring survival is on the rise in Lake Michigan despite the fact that their parents are up to 70 mm shorter now than they were in the 1970s.

“We were expecting to see a decrease in productivity because the adults are maturing at smaller sizes, which should mean fewer eggs and less healthy hatchlings,” said Zach Feiner, a PhD student at Purdue University and lead author of the study. “This raises a lot of questions about how well we understand rainbow smelt fisheries.”

Researchers speculate that the drop in the number of adult smelt may actually be allowing hatchlings to thrive. Adult rainbow smelt frequently supplement their diet of zooplankton by dining on their offspring. Fewer adults means fewer predators for juvenile smelt. The need to find food in a lake infested with millions of quagga and zebra mussels that filter out plankton may also be driving adults further out into the lake and away from spawning grounds.

***Photo courtesy of Crystal Lake Mixing Project.

The Zephyr project area is located along the North Branch of the Muskegon River in the Muskegon Lake Area of Concern (AOC), Muskegon, Michigan. For more than 40 years, the Zephyr Oil Refinery operated with historic releases of petroleum and metals into the Muskegon Lake watershed. These releases contributed to significant contamination of the sediment and wetlands surrounding the site and resulted in the loss of fish and wildlife habitat, as well as other beneficial use impairments (BUIs) to the AOC. The Zephyr project was identified in the Stage 2 Remedial Action Plan for the Muskegon Lake AOC for restoration in order to support BUI removal. Under the Great Lakes Legacy Act, through the strong partnership between the U.S. EPA GLNPO and MDEQ, the project was completed in late 2018.

The Zephyr project area is located along the North Branch of the Muskegon River in the Muskegon Lake Area of Concern (AOC), Muskegon, Michigan. For more than 40 years, the Zephyr Oil Refinery operated with historic releases of petroleum and metals into the Muskegon Lake watershed. These releases contributed to significant contamination of the sediment and wetlands surrounding the site and resulted in the loss of fish and wildlife habitat, as well as other beneficial use impairments (BUIs) to the AOC. The Zephyr project was identified in the Stage 2 Remedial Action Plan for the Muskegon Lake AOC for restoration in order to support BUI removal. Under the Great Lakes Legacy Act, through the strong partnership between the U.S. EPA GLNPO and MDEQ, the project was completed in late 2018. “Community outreach was a priority and a team effort at Zephyr,” said Caitie Nigrelli, environmental social scientist with the U.S. EPA and Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant. “We were digging up petroleum-based contaminants upwind of a neighborhood. We wanted to be a good neighbor. We needed to know that our project was maintaining air quality standards, and had a plan in place to communicate that. We went door to door before construction started to alert neighbors of potential odors and thank them in advance for their patience.”

“Community outreach was a priority and a team effort at Zephyr,” said Caitie Nigrelli, environmental social scientist with the U.S. EPA and Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant. “We were digging up petroleum-based contaminants upwind of a neighborhood. We wanted to be a good neighbor. We needed to know that our project was maintaining air quality standards, and had a plan in place to communicate that. We went door to door before construction started to alert neighbors of potential odors and thank them in advance for their patience.”