September 29th, 2021 by Irene Miles

Every summer, Lake Erie’s central basin develops hypoxia, or a dead zone, where oxygen is too low for most aquatic life to survive, but the size and distribution of that zone varies from year to year. To help in monitoring the lake’s hypoxia extent and concentrations, as well as assessing the quality of its fish habitat, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) researchers have developed a 3-dimensional model that maps out low oxygen areas.

Hypoxia can develop when phosphorus, often from nearby farm fields or industry, drains into local waters, leading to rapid growth of algae on a lake’s surface. As these organisms die off, they sink to the bottom and decompose, a process that uses up much of the available oxygen. As the shallowest of the Great Lakes, Lake Erie is particularly prone to algal blooms and hypoxia.

“The lake is predisposed to particularly drastic swings in habitat quality over time,” said Joshua Tellier, a biologist with the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy who worked on this project while he was a Purdue University master’s student. In the central basin, in summer, the water develops distinct temperature layers, separating the lake’s colder bottom from oxygen-rich surface waters, setting the stage for hypoxic conditions.

Tellier used nearly 25 years of monitoring data from the U.S. EPA Great Lakes National Program Office (GLNPO) and U.S. Geological Survey that consistently measured dissolved oxygen levels and temperatures at numerous sites throughout the central basin to model hypoxia in Lake Erie. This 3-D model also reflects changes in habitat quality.

“The main component negatively affecting habitat quality is the seasonal decrease in oxygen levels. We can connect the oxygen concentrations and the extent of hypoxia to habitat quality for fish over time,” he said.

This project is part of Tellier’s thesis for his master’s degree in Purdue’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources. IISG’s Paris Collingsworth, Great Lakes ecosystem specialist, and Tomas Höök, director, are his advisors. Funding comes through IISG’s long term grant with U.S. EPA GLNPO.

The team tested how hypoxia and habitat quality affect three Lake Erie fish species—rainbow smelt, round goby and yellow perch. These three fish are common in the central basin, but they also each have different life strategies. Smelt are on the surface and eat plankton that float in open waters; gobies, on the other hand, are bottom feeders; and yellow perch are adaptable, taking advantage of both strategies.

The modeling revealed habitat quality for the three fish species over time, reflecting hypoxia’s impact on their ranges and locations.

With hypoxia situated at the lake bottom, when it is severe, gobies often need to move to another location where conditions are more suitable for them. Smelt have a more complicated story. They prefer to be in colder water, so when the lake’s upper layer heats up during the summer, they move down lower in the water. But, the low oxygen conditions at the bottom don’t work either.

“We find that when hypoxia is present, the smelt are basically sandwiched into the tiny interface layer between the bottom hypoxic water, and the upper warm water. We think they’re being thermally squeezed from above, and squeezed by oxygen stress from below,” said Tellier.

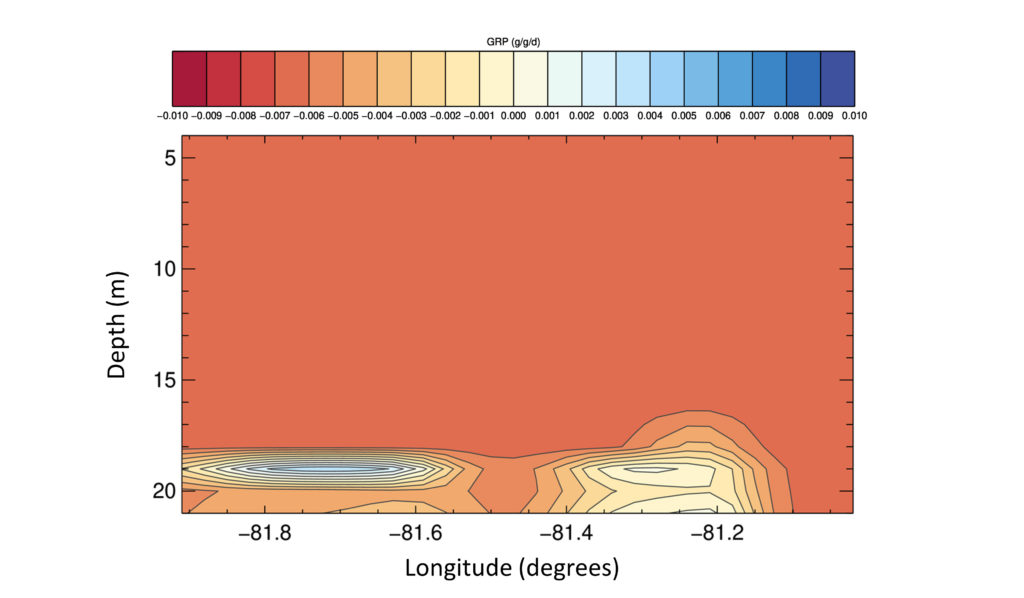

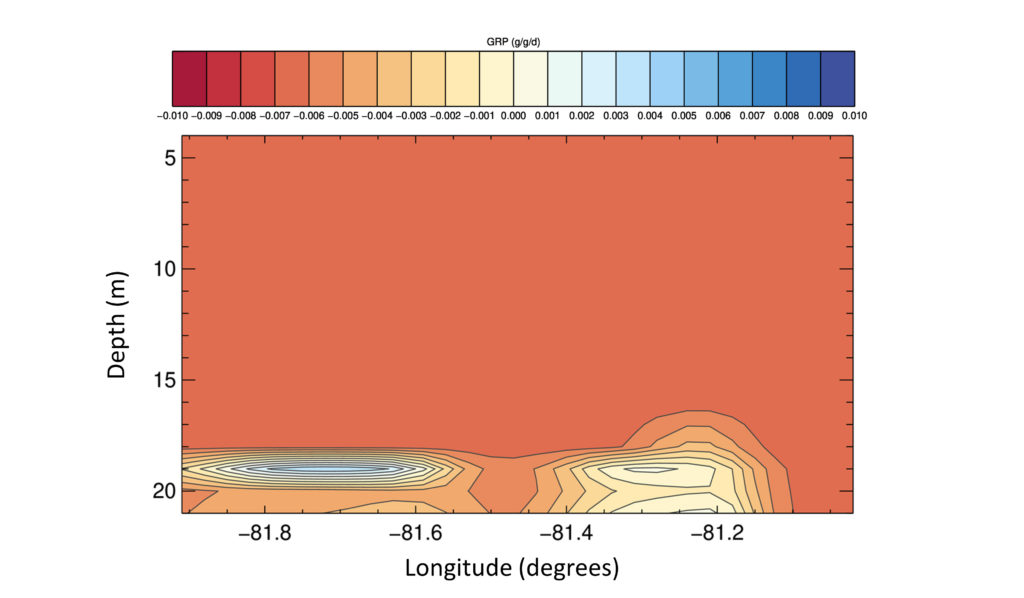

Looking at the central basin of Lake Erie from top to bottom using Tellier’s 3-D model reveals that during the hypoxic season, smelt find refuge in a thin band of habitat, shown here in the bluish area.

“Because they are adaptive, perch have many foraging strategies that they can use to survive in a wide range of conditions,” he explained. Studies have shown that perch will dive down into hypoxic waters because the benthic prey there is richer in energy than what they could otherwise find. “The perch are taking some sort of tradeoff where they’re saying, ‘it might tax my metabolism and my health to go down into this water, but there is a rich food resource in there—that’s worthwhile,’” Tellier added.

“Josh’s research is timely,” said Collingworth, “because the management community in Lake Erie is currently considering ways to determine if their actions are producing noticeable changes in the lake. These models can be used to provide meaningful biological endpoints related to fish habitat quality.”

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

Writer: Irene Miles

September 27th, 2021 by Irene Miles

This year, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant has continued to grow as a program. We welcome new expertise and offer expanded opportunities to students and stakeholders both as groups and individuals.

I’m pleased to announce that Shiba Kar is our new associate director as part of his new position as the assistant dean and program leader for natural resources, environment, and energy for University of Illinois Extension. Dr. Kar, whose experience in natural resource sustainability spans three countries—the U.S., Bangladesh, and Australia, came to Illinois from the University of Wisconsin. We look forward to his fresh ideas and support.

At IISG, an important part of our work is to offer opportunities to help advance scientists in the early days of their careers. We are proud to announce our two finalists for the 2022 Knauss Fellowship Program. The one-year fellowship places beginning professionals in federal government offices in Washington, D.C.

Gabriella Dawn Ketch is a PhD student at Northwestern University who is quantifying geologic ocean acidification events as part of her dissertation in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. Cynthia Garcia Eidell is working toward her doctorate in the University of Illinois Chicago Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences. She is studying carbon cycles along the Arctic coast. Both will begin their fellowship in February in either the Executive or Legislative branch.

We are also supporting nine new research projects through the Sea Grant Scholars program. The scholars program helps develop a community of scientists to work on critical issues related to Lake Michigan and the Great Lakes region through funding and other opportunities for one year.

As one of three faculty scholars, Sachit Butail of Northern Illinois University seeks to improve the design of robotic sampling of an invasive spiny water flea in the Great Lakes. Ramez Hajj, at the University of Illinois, will develop a porous asphalt mixture capable of resisting freeze-thaw cycles. And at the Illinois Institute of Technology, David Lampert will develop a stormwater model to assess impacts on hydrology and water quality in southern Lake Michigan communities.

In addition to these faculty members, six graduate students received funding through the scholars competition to extend their research activities.

I’d also like to share some details of our work in response to COVID-19. In 2020, the National Sea Grant Office awarded funding to state programs to quickly provide resources to stakeholder groups experiencing impacts from the pandemic and the associated shutdowns. A year later, here’s how we were able to help in the moment, and down the road.

In Illinois and Indiana, aquaculture producers generally sell live fish to restaurants and through ethnic markets. When these avenues closed down last year, we helped fish farmers apply for financial support, but also, explored processing options that could open up new markets and increase farmers’ resiliency. Eleven farmers took part in online training for HACCP, a food safety process. Several have since expanded their businesses and others have the information and skills to do so.

Around Lake Michigan, many charter fishing operators were forced to suspend their businesses in 2020 just as the fishing season was starting. And, they were not eligible for the initial financial rescue packages. We built a charter fishing network, providing operators regular updates and publications on potential financial assistance and best practices for reopening. Working with Michigan and Wisconsin Sea Grants, we surveyed charter operators and found that, on average, they each lost $10,0000–$15,000 in revenue in 2020, resulting in at least $8 million in lost revenue across the fishery due to COVID-19.

Now more than ever, teachers need to find lessons that are adaptable to different learning environments and cover required curriculum topics. We created the online Weather and Climate Explorer to allow educators of all sorts to filter their search for activities and lessons by grade levels, specific weather and climate subtopics or geographic locations, learning modes, and more.

Building on this rapid response grant project, the Explorers became an education series. The Pollution Prevention Explorer covers a range of water pollution sources—including microplastics and beach debris—and potential responses in its lessons and other resources. And in a similar theme, Land to Water: The Nutrient Explorer is focused on causes and impacts of excess nitrogen and phosphorus that wash into rivers and lakes.

Tomas Höök

Director, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

September 2nd, 2021 by Irene Miles

In March of 2020, when the world as we know it quickly shut down due to COVID-19, many Lake Michigan charter captains were just about to kick off the fishing season. While most of these businesses were able to fire up their motorboats later in the summer, on average, Lake Michigan charter operators each lost $20,000 last year. Lake wide, the setback was $9.2 million.

“May is a very busy month in the charter business, and usually helps pay for most of our startup costs,” said David Smith, a charter operator from Gurnee, Illinois. “In 2020, we were way behind the profit level once the marina was opened.”

Add to that, the first round of COVID-19 federal financial support for fishing businesses did not include the Great Lakes.

In the midst of this, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant set out to provide immediate assistance to charter operators and to help them navigate COVID guidelines. Plus, Mitch Zischke, IISG fisheries specialist, assessed the economic impacts of the pandemic on charter fishing businesses. Funding for this effort was provided by the National Sea Grant Office.

“We quickly built a network of charter boat operators and business owners registered in Illinois and Indiana and provided them regular updates and links to financial aid, a fact sheet, and other resources,” said Zischke. “I was sending out emails, probably once a week, to keep them up to date on how things were changing.”

In June, as restrictions on outdoor activities eased up, many charter captains had questions and concerns about taking anglers out on their boats with COVID still a significant concern. Zischke developed and distributed a publication that provided guidance on best practices for reopening safely, addressing proper cleaning and social distancing, to name a few topics covered.

Zischke also joined with Dan O’Keefe and Titus Seilheimer, his counterparts at Michigan and Wisconsin Sea Grant programs, respectively, to send two surveys to charter boat operators around the lake to get a better understanding of how the pandemic affected their businesses early on and later in the season. In a typical year, the 1,000 Lake Michigan charter fishing businesses engage in about 12,000 trips.

Through June, as many as 37% of charter captains in Illinois and Indiana had not fished at all. Around the lake, captains reported a 50-65% drop in trips, which translates to $5,000–$15,000 loss of income compared to 2019.

“Because the season in the southern Lake Michigan region starts earlier than up north, charter operators in Illinois and Indiana took a bigger hit,” said Zischke.

The second half of the fishing season picked up considerably for charter operators, but lake wide, they each still reported, on average, a loss of just under $3,000 as compared to 2019. Altogether, the total shortfall from June to October was $2 million. Combined with a loss of $7.2 million in the early part of the fishing season, the captains suffered a setback of $9.2 million in 2020 as compared to 2019.

The survey revealed that some captains laid off employees or lowered their rates in 2020 and 35% applied for financial aid. Concerns for the future are considerable.

For example, Smith talked about supply chain problems. “It is hard to get fishing line, rods, reels and other items to make sure the boat is running in tip-top shape. If you don’t have extra parts, which I’ve stocked up this year, you might have issues being able to run charters.”

To help these small business owners be more resilient, Zischke is working with the Purdue Institute for Family Business and the Community Develop Extension team to develop training sessions.

“We’re going to cover how to develop a business plan and contingency plans for when something like a pandemic throw things off track, as well as introduce some digital tools that they can incorporate into their charter fishing businesses, like electronic payments, search engine optimization and social media,” said Zischke.

He plans to share these educational opportunities with southern Lake Michigan charter captains this winter.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

Writer: Irene Miles

Contact: Mitch Zischke

August 31st, 2021 by Irene Miles

The record high Lake Michigan water levels in 2020 were even more dramatic if you consider that the lake had near record low levels as recent as 2013.

“That’s a lot of pressure on the shoreline,” said Cary Troy, Purdue University civil engineer. “There’s really no precedent in terms of ocean coastlines for what the Great Lakes are going through related to water level fluctuations.” In addition to lake levels, beaches are impacted by large storms and barriers, piers, and other human interventions.

Troy is part of a sweeping study funded through Illinois-Indiana, Michigan and Wisconsin Sea Grant programs to assess Lake Michigan coastal erosion levels, causes, and management options from physical, social and community perspectives. The two-year project that began in 2020 is led by Troy, Guy Meadows with Michigan Technological University and Chin Wu at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Miles Tryon-Petith, Chin Wu’s civil and environmental engineering Ph.D. student from UW-Madison is working on mounting the real-time camera to record bluff movement in Mequon, Wisc. (Photo courtesy of Wisconsin Sea Grant.)

The research will focus on three coastal communities that offer the opportunity for scientists to track and measure erosion on different beach features—the bluffs at Concordia University in Wisconsin, the shoreline of South Haven, Michigan, and the dunes at Beverly Shores in Indiana.

Part of the beach in the small town of Beverly Shores is in the Indiana Dunes National Park—there, the research team can learn more about how nature responds to water level changes and storm events. Troy also wants to study coastal sites where people have added structures to the landscape. He’s trying to understand the different ways that the shoreline is affected by both the changing conditions and human-made structures.

“The Indiana coastline—and to some degree the Illinois coastline—I call it a confluence of competing interests,” said Troy. “You have this beautiful, natural Indiana Dunes National Park lakeshore and then you look to your left and there’s a giant steel mill, and then to the right and there are multimillion dollar homes. And then there are public beaches and harbors, and it’s really a lot of different kinds of shoreline use packed into a very small space.”

The scientists will gather data using a variety of technology that will allow them to monitor the effects of individual storms as well as help tell the bigger story. Using drones equipped with LiDAR, which uses laser beams to measure distances, they can quantify changes to the beach that occur due to storms. The research team has ready access to a LiDAR system developed by Ayman Habib, a civil engineer at Purdue, who also created a backpack-based system that can be used to perform high resolution mapping of the beach while walking along the shoreline.

But the best data may not make enough of a difference if community decision makers or even neighbors are at odds about how to manage Lake Michigan’s shores, so the project team includes social scientists who are focusing on the root causes of community conflict on this issue. The goal is to develop better community planning processes for shoreline protection and restoration.

Robert Enright, a UW-Madison psychologist, and his Ph.D. student, Lai Wong, will employ social justice circles, a scientifically verified program that works to address issues about which people feel strongly. This method convenes opposing parties in a dialogue with the goals of fostering understanding and mutual problem-solving.

For his part, Aaron Thompson, a social scientist at Purdue, will survey landowners in Beverly Shores to get a baseline understanding of their knowledge about coastal management and their attitudes towards past and possible future efforts to solve this problem.

“When lake levels were high last year, Beverly Shores residents did not lose any structures because they don’t have homes right on the shoreline,” said Thompson. “But, the community is potentially facing millions of dollars in infrastructure repair costs because sections of a coastal road washed away, along with the utilities underneath.”

The survey will include questions that address residents’ knowledge of and reactions to likely management options, derived through modeling of the sites with new data. The options will include nature-based solutions, which can be features that are completely natural, like planting native vegetation on dunes, and those that are “hard,” such as concrete structures like seawalls.

While most project activities were delayed due to the pandemic, Troy and his undergraduate students, Ben Nelson-Mercer and Hannah Tomkins, were able to use that time to analyze historical and recent aerial photographs of the Indiana lakeshore.

“We’ve been looking at parallels between the recent rapid increase in water levels from 2013 to 2020 with historical periods where the water level has also risen very rapidly,” said Troy. They went back to the 1960s, 80s and 90s to compare impacts to the shoreline.

Their results are preliminary, but they seem to be good news. “The shoreline erosion that we saw during this last period was pretty consistent with what we’ve seen in other periods where the water level has risen rapidly, which suggests that it’s a cycle,” Troy said.

They also noticed that, thus far, the shoreline position following the rapid water level increase in 2020 seems to be in slightly better shape than after previous high water level periods.

“Not to downplay the damage that we’ve seen along the Lake Michigan coastline, but there is historical precedent that suggests that the beaches will rebound quickly, provided that the water level comes down,” added Troy. “We find that beach rebuilding happens during the period when the water level is dropping. That said, it’s anyone’s guess where the water levels will go at this point, so we have to be prepared for all possibilities.”

Read more about how this project is going in Michigan and Wisconsin on their Sea Grant program websites.

Additional funding for this project is being provided by the Michigan Coastal Management Program, a NOAA Coastal Resilience grant and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources Lake Michigan Coastal Program.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

Writer: Irene Miles

Contact: Carolyn Foley

June 28th, 2021 by Irene Miles

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) announces support for nine new research projects through the Sea Grant Scholars program. The scholars program helps develop a community of scientists to work on critical issues related to Lake Michigan and the Great Lakes region through funding and other opportunities for one year.

This is the third cohort of IISG faculty scholars—they will spend their scholar year working with stakeholders or program specialists to develop preliminary research products and develop at least one proposal to another funding source. This is the first group of graduate student scholars.

As one of the three faculty scholars, Sachit Butail of Northern Illinois University seeks to improve the design of robotic sampling of spiny water flea (Bythotrephes longimanus), an invasive microorganism in the Great Lakes. Ramez Hajj, who is located at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, will develop a porous asphalt mixture capable of resisting freeze-thaw cycles. And at the Illinois Institute of Technology, David Lampert will develop a stormwater model to assess the effects of water infrastructure as well as land use on hydrology and water quality in southern Lake Michigan communities.

“Since the program’s inception, the breadth of topic areas covered by faculty scholars, plus the innovative ideas that come out of the work, have been quite exciting,” said IISG research coordinator Carolyn Foley.

In addition to faculty members, six graduate students received funding through the scholars competition to extend their research activities, while an additional eight graduate students will join them in professional development activities.

“We are looking to expand the students’ knowledge base, give them a sense of the overall Sea Grant program’s priorities of combining research, communication, and outreach or extension activities, and help them broaden the impact of their work,” added Foley. “However, we hope that they also take away a network of professionals that they can rely on in the next stage of their careers.”

Watch for the graduate student scholars to share their stories over the next year via IISG social media channels (Facebook | Twitter | Instagram | YouTube). IISG’s research database provides a full list of scholar and other research projects supported by the Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant program.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

Writers: Carolyn Foley, Irene Miles

Contact: Carolyn Foley

April 30th, 2021 by Irene Miles

Happy spring, everybody! While none of us know what to expect in terms of COVID-19 this summer or fall, some aspects of normal life are returning. For example, research and monitoring on the Great Lakes is back—with new COVID guidelines. Through the Cooperative Science and Monitoring Initiative, this year, we are looking forward to being out and engaged in research on two lakes—Lake Michigan and Lake Superior—to make up for last year’s cancellations.

In other news, our ace aquaculture team is creating new opportunities for consumers to learn more about local aquaculture and eating fish as part of a healthy diet. Amy Shambach, aquaculture marketing outreach associate, has created Eat Midwest Fish, a website that’s full of information, including a fish finder map that shows users where fresh seafood is produced.

We’ve also kicked off a video series, Local Farmers, Local Fish, highlighting Illinois and Indiana aquaculture producers, with RDM Shrimp, located in Fowler, Indiana. Since the husband and wife team opened their doors in 2010, they have been raising Pacific white shrimp for the consumer market and teaching others how to do the same.

In other areas, we’re developing education compendiums for teachers and parents to bring lessons and activities about natural resource issues to young learners. Freedom Seekers: The Underground Railroad, Great Lakes, and Science Literacy Activities acknowledges the enslaved Africans who had to rely on environmental science principles in their quest for life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Our Explorer Series began last year with a focus on weather and climate. This collection of educational resources is sortable by grade, topic, learning mode and more to make it easy to find what you need. New explorer collections will discuss pollution sources, tracking contamination levels, and ways to prevent pollution. The NLRS Explorer, addressing nutrient pollution, will be coming soon, and the Pollution Prevention Explorer, which touches on a variety of types of contaminants—including medicines and plastics in local waterways—will be ready later this year.

Along these lines, eight educators who, over the years, have set sail on the Sea Grant Shipboard Science Workshop aboard the EPA research ship, the Lake Guardian, have shared how that experience has made a difference in their teaching and their students’ lives. You can read their inspiring stories in Educators Onboard for Learning.

I am happy to announce that we have three new staff members who have recently joined us. Two positions are located in the EPA Great Lakes National Program Office and will focus on Area of Concern (AOC) remediation, restoration and revitalization.

First, Ashley Belle has switched roles in University of Illinois Extension—previously, she was an environmental and energy stewardship Extension educator and is now our Great Lakes AOC specialist who will engage in outreach with communities going through the cleanup process. Beata Fizser is our new AOC revitalization educator. She comes to IISG from Invenergy LLC, where she was a senior analyst on culture, innovation and impact.

Ben Szczygiel has joined Purdue’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources and IISG as a buoy and aquatic ecosystem specialist. He is coming from the State University of New York in Buffalo where he was a research assistant and will now be managing our buoy program.

We welcome these new members of our team!

Tomas Höök

Director, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

April 1st, 2021 by Irene Miles

Each summer on one of the Great Lakes, 15 educators set sail for a week on the Lake Guardian, an Environmental Protection Agency research vessel, where they work side by side with scientists and fellow educators, growing their knowledge and confidence in bringing Great Lakes science to their students.

The Shipboard Science Workshop is the centerpiece project of the Center for Great Lakes Literacy, a collaborative of education specialists from Sea Grant programs in the region and funded through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. Since 2006, 207 educators have taken part in this adventure.

The hands-on, immersive nature of this experience fosters a broader and deeper understanding of science—the educators onboard are developing research skills as they engage in real world scientific investigation. They also expand their “treasure box” of lessons, teaching strategies, and network of like-minded colleagues. Participants of the workshops have described them as once-in-a-lifetime professional development opportunities.

Educators from every Great Lake state described how participating in the Shipboard Science Workshop has impacted them and their students. You can read their experiences in a new story map: Educators Onboard for Learning.

January 25th, 2021 by Irene Miles

In light of last year’s high water levels in Lake Michigan and other Great Lakes, repeatedly breaking monthly records, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) brought together resource managers, experts, scientists and community leaders in October to improve understanding of changing lake level impacts and management implications. The group began a process of sharing information and ideas.

While lake levels reached a high mark in 2020, not long ago, in 2012−13 in fact, Lake Michigan’s water level was at a record low. At the time, hydrologists and others were concerned about ships navigating in shallower waters and the need for dredging, among other issues.

Conversely, record and near-record high water levels in 2020 led to submerged docks, flooded transportation infrastructure, including Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive, inundated coastal areas and eroding shorelines. Higher water levels can cause irreversible, lasting damage to the shoreline and structures, as well as to habitats.

The virtual workshops, which took place over four afternoons, were focused on the southwestern Lake Michigan region, which includes Chicago and industrialized areas south of Chicago and in Indiana, as well as unique stretches of precious coastal habitat such as the Indiana Dunes National Park, along with other state-protected natural areas.

With 30−40 participants each day, the sessions combined presentations with small group discussions to identify specific issues and define available and needed resources. These conversations brought some common themes to the front.

With 30−40 participants each day, the sessions combined presentations with small group discussions to identify specific issues and define available and needed resources. These conversations brought some common themes to the front.

“Participants stressed the need to keep up with the best available science and experts in the field,” said Veronica Fall, IISG climate specialist. Fall, along with Carolyn Foley, the program’s research coordinator, organized and hosted the workshop series.

In addition, the discussions brought out the need to apply information to long-term planning and management, given projections for increased water level variability, and, specifically, water safety concerns were highlighted.

The group also focused on the need to share information, stressing the importance of knowing people’s expertise so that it is clear whom to contact with questions. Participants expressed the importance of engaging and sharing information with diverse audiences.

“They agreed on the need to pull together lists of available resources for use by Lake Michigan shoreline communities, and ensure these are being equitably shared,” said Foley. “Some participants have already indicated that they will be revising how they share information in response to thoughts shared during these workshops.”

You can find the workshop report in IISG’s publications database. Presentations by workshop participants from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Weather Service, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Cook County Emergency Management and Regional Security, the Illinois State Geological Survey, and more are available via IISG’s YouTube channel.

Workshop Videos

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

Writer: Irene Miles

December 18th, 2020 by Irene Miles

As 2020 comes to an end, we say good-bye to a long and challenging year, to say the least. We’ve all coped with changes and losses, large and small, as we’ve lived through this pandemic.

Like everyone, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) has worked to adapt. We’ve also sought out ways to provide support for our stakeholders to adapt in these times. We developed initiatives to help aquaculture producers and charter fishermen find new ways to be successful. And we’ve helped teachers pivot to online learning with new resources and opportunities, including our Scientist to Student program that uses video chats to bring scientists into students’ homes to talk about the Great Lakes and related science.

In 2020, our podcast, Teach Me About the Great Lakes, kicked into high gear. As the year took its many turns, Stuart Carlton worked to make the conversations relevant to our lives. He talked to experts about spending time in nature while we live with the threat of COVID-19 and actively brought a more diverse group of Great Lakes scientists into the podcast conversations.

Late in the year, IISG, together with Purdue Extension and the university’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, launched a new podcast series. Mitch Zischke and Megan Gunn are co-hosting Pond University, covering related topics such as habitat, fish stocking, vegetation control and construction, and will feature conversations with aquatic scientists, landowners and pond professionals.

Related to another issue of elevated concern, we held a series of workshops for resource managers and community leaders in the southern Lake Michigan region to discuss the lake’s record-breaking high water level and extreme water level variability in the last decade. The group ended the meetings with enthusiasm for further discussion and a list of available and needed resources.

As we look to the new year, it brings new opportunities, as always, but also a chance to make up for some of this year’s setbacks.

First of all, two IISG specialists moved on to other opportunities in 2020 and their professionalism and enthusiasm are very much missed. Jay Beugly was responsible for our buoys—their upkeep, installation and removal each year. But he also worked as an aquatic ecologist who engaged students in learning about fish in local waterways. Caitie Nigrelli is a social scientist who provided critical outreach to Great Lakes Areas of Concern communities undergoing the cleanup process. Before she left, Caitie developed a new position to assist in these efforts. Now, the process is ongoing to fill all three of these openings. What’s more, we are accepting applications for an associate director for the program, situated at the University of Illinois.

This year was scheduled to be a big year for Lake Michigan research through the Cooperative Science and Monitoring Initiative, which brings together scientists from around the Great Lakes to focus on one lake each year. This research and monitoring effort didn’t happen in 2020, but some studies will take place in the coming year after all, making for a busy field season on Lake Michigan and Lake Superior.

Speaking of research, a new study carried out by three Sea Grant scientists, including our Carolyn Foley, found that Sea Grant-supported research is consistently published in high quality journals and is frequently cited in local, regional and international publications. We continue supporting research relevant to our region, so this week we announce our new Request for Proposals with a particular focus on local food—specifically, fish and seafood—as well as changing lake levels, water safety and many other Great Lakes issues.

We are also expanding our research funding opportunities. In the coming year, we expect to release a request for applications to a new Graduate Student Scholars program. Current graduate students in Illinois and Indiana will be able to apply for funding to expand their research and will have opportunities to learn from Sea Grant specialists about a variety of topics related to effective outreach and communication.

With hope for better days soon, we wish you happy holidays!

Tomas Höök

Director, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is a part of University of Illinois Extension and Purdue Extension.

With 30−40 participants each day, the sessions combined presentations with small group discussions to identify specific issues and define available and needed resources. These conversations brought some common themes to the front.

With 30−40 participants each day, the sessions combined presentations with small group discussions to identify specific issues and define available and needed resources. These conversations brought some common themes to the front.